There’s an old saying that you can’t step in the same river twice. But a group of researchers have now retraced an ancient, buried Nile tributary — allowing historians to walk in the dried-up waterway path that probably proved instrumental in the construction of the 31 pyramids it once flowed past.

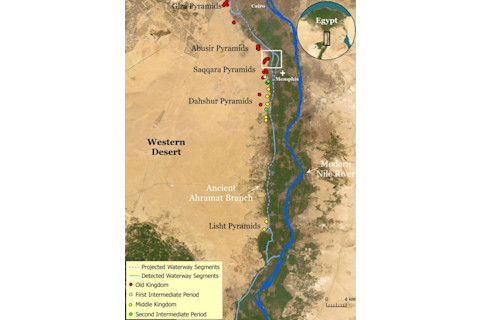

A report in Communications Earth & Environment employed satellite imaging, ground-penetrating radar, and soil samples to show that these famous structures — including the Giza complex — may have been built along a now dry 40-mile stretch of the river Nile. Many archeologists interested in ancient Egypt had long suspected that tomb and pyramid builders used a waterway to transport materials and workers to building sites.

“Nobody was certain of the location, the shape, the size, or proximity of this mega waterway to the actual pyramids site,” says Eman Ghoneim, a researcher with University of North Carolina Wilmington. “This is what motivated our research team to investigate.”

Finding the Nile Tributary

Ghoneim and her team used multiple tools to identify, then validate, the tributary’s location.

First, they employed radar satellite data and radar-derived digital elevation to map the tributary they named the Ahramat Branch. Next, they used ground-penetrating radar to confirm its path. Finally, they took soil samples that showed the presence of sediment consistent with riverbeds.

“Radar waves strip away the desert sand layer and expose previously unknown buried river channels,” says Ghoneim. “Deep soil coring and geophysical surveys from the field were used afterwards to validate the radar satellite mapping and prove the presence of the branch in the Nile Floodplain.”

Read More: The Nile Was a Lifeline in the Desert for Ancient Nubia and Egypt

The water course of the ancient Ahramat Branch borders a large number of pyramids dating from the Old Kingdom to the Second Intermediate Period, spanning between the Third Dynasty and the Thirteenth Dynasty. (Credit: Eman Ghoneim)

Eman Ghoneim

An Ancient Superhighway

This work further cements the importance of waterways to Egypt’s prosperity during the 1,000-year period when the pyramids were built, starting about 4,700 years ago.

“For millennia, the Nile River has played a fundamental role in the rapid growth and expansion of the Egyptian civilization," Ghoneim says. “For dynastic period Egyptians, the Nile was the source of livelihood and a “superhighway” that allowed for the transportation of their goods and building materials.”

The pyramids’ proximity to the waterway underscores how several structures fit together along with the river.

“The Egyptian royal pyramids are not solitary monuments; rather, they are part of complexes that include many other buildings,” says Ghoneim.

Read More: A Three Millennia Mystery: The Source Of The Nile River

Causeway Connection

The complexes include the pyramid itself, a nearby mortuary temple, a valley temple and a long, sloping causeway that links the two temples. The map the researchers created better shows how these individual entities links.

“Our research shows that several surviving causeways in the study area run perpendicular to the Ahramat Branch's course and end with Valley Temples, which are situated right on the Ahramat Branch's riverbank,” says Ghoneim. “In the past, these valley temples served as river harbors.”

Despite identifying the Ahramat Branch, much work remains to better understand the ancient Nile network. Finding and mapping more tributaries could reveal other hidden Egyptian archeological treasures — or, at minimum provide a better understanding of how people and goods moved through the region.

But for now, Ghoneim and her team are enjoying their results in connecting the dots between the pyramids and the Nile’s tributary.

“I have to admit that this was a very rewarding feeling!” Ghoneim says.

Read More: How the Nile River Has Stayed In One Place for 30 Million Years

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Researcher with University of North Carolina Wilmington. Eman Ghoneim.

Communications Earth & Environment. The Egyptian pyramid chain was built along the now abandoned Ahramat Nile Branch.

Before joining Discover Magazine, Paul spent over 20 years as a science journalist, specializing in U.S. life science policy and global scientific career issues. He began his career in newspapers, but switched to scientific magazines. His work has appeared in publications including Science News, Science, Nature, and Scientific American.