Kate Spradley slips blue hospital booties over her leather flats before stepping through the double security gate of a high fence surrounding a 26-acre outdoor research area on the Freeman Ranch in San Marcos, Texas. With her shoes safely covered to avoid contaminating the scene, she walks up to the cadavers laid out in the tall grass and notes the broken ribs and shattered eye sockets, the remains picked over by vultures.

Spradley is a biological anthropology professor at Texas State University, owner of the Freeman Ranch. She collaborates on her fieldwork there with Michelle Hamilton, a forensic anthropology professor also at Texas State. The two are trying to provide more accurate information in death investigations by studying how vulture behavior, combined with weather and geography, can modify human remains.

Vultures expose bones to rapid weathering and carry remains beyond the body’s immediate location. These factors, sometimes missed by investigators and CSI types, can alter time-of-death estimates. Indeed, the duo’s first 2011 study showed that vultures took roughly a month to locate a planted human body but picked it clean in just five hours. Now, they’re expanding that research.

The current study, which they hope to publish this year, examines eight donated bodies in various micro-environments, mimicking possible crime scenes, throughout the Freeman Ranch field. Some remains lie on hard ground with minimal grass coverage, while others are partially or fully shaded under native plants, such as juniper trees.

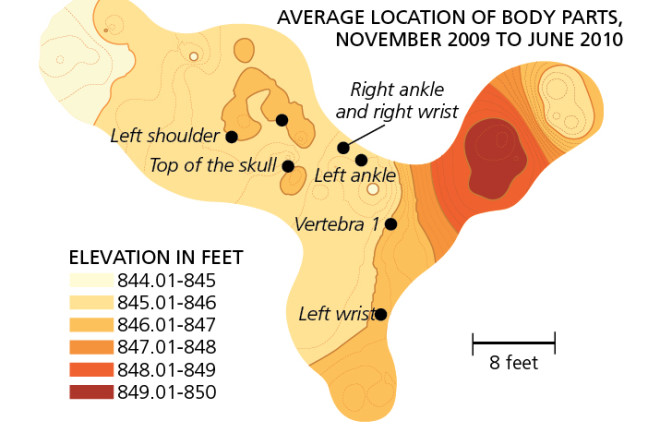

Using motion-activated cameras and detailed field notes, Spradley and Hamilton documented vultures’ feeding habits, including how long they take to locate remains. The researchers also construct detailed maps to document how the birds distribute remains across different sites.

“If the vultures scatter the bones in a very predictable environment,” Spradley notes, “then we can educate law enforcement … on how to do recovery [and] where to look.”

An accurate time of death or recovering enough of a body for a successful identification could make all the difference to a family of a missing child or a defendant in a murder trial. It’s truly a matter of life and death.