Hans Berger could do nothing as the huge field gun rolled toward him.

In 1892, the 19-year-old German had enlisted for military service. One spring morning, while pulling heavy artillery for a training session, Berger’s horse suddenly threw him to the ground. He watched, helpless and terrified, as the rolling artillery came toward him, only to stop at the very last minute.

At precisely the same moment, Berger’s sister — far away in his hometown of Coburg — was struck by a premonition, an overwhelming sense that something tragic had befallen her brother. She begged her father to send him a telegram to make sure he was OK. Berger was stunned by the coincidence. “It was a case of spontaneous telepathy,” he later wrote of the incident.

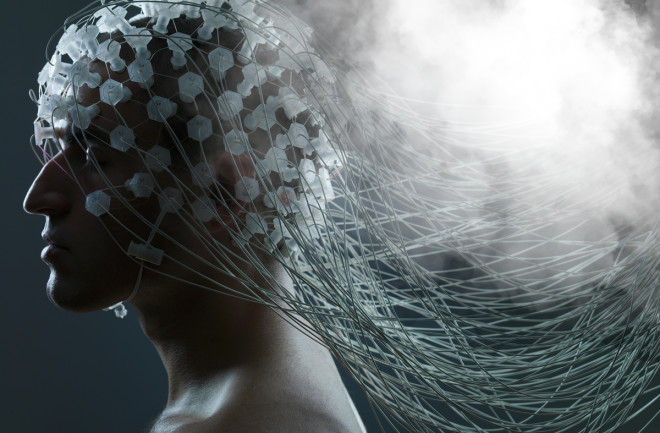

Determined to make sense of the event and what he called “psychic energy,” Berger began to study the brain and the electrical signals it gave off during wakefulness. In a sense, he succeeded. His efforts to record the small electrical signals that escape from the brain and ripple across the scalp have given us one of the key tools for studying sleep, the electroencephalogram (EEG), or, as Berger described it, “a kind of brain mirror.”

In 1929, Berger published his discovery. As others looked to replicate Berger’s work, they realized the EEG revealed electrical activity during sleep, too. Based on the EEG signature, researchers could show there were several different stages of sleep, and the sequence and timing of them underpins the diagnosis of many sleep disorders. But in the first few decades of using the EEG, there was one stage of sleep nobody noticed.