One day in April 2014, Mathilde Tissier noticed her hamsters were acting a little odd. The Cricetus cricetus in her lab at the University of Strasbourg in France, once happily subsisting on a corn-based diet, were now banging their feeder against the cage, their tongues swollen and black, and had begun to eat their pups alive. As Tissier reported in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B in January 2017, she suddenly had cannibal hamsters on her hands.

“I was shocked,” says Tissier, a conservation biologist. “I thought I did something wrong.” Searching for an explanation, Tissier teased out a thread that wove through America’s past. Some of the symptoms she saw in both the mothers and surviving pups resembled those of a debilitating disease called pellagra. The illness affected more than 3 million people and killed more than 100,000 in the United States, primarily in the South, between 1900 and 1940.

The quest to understand and cure the outbreak combined research, social politics and economic forces — and, as Tissier saw firsthand, it’s a history we’d do well to remember.

Scourge of the South

In the early 1900s, cases of a mysterious malady started appearing every summer in the South. At first, patients felt melancholy and weak. Some then developed swollen tongues and drooled excessively. As the disease advanced, people displayed a symmetrical photosensitive rash across their limbs, neck and face. Some patients’ symptoms disappeared a few months later, only to recur the following year. For others, the disease progressed through the four Ds: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia and death.

In 1907, physicians at two Southern mental institutions began to suspect their patients’ symptoms were the result of pellagra, Italian for “rough or dry skin.” The disease was first identified in 1735 by Spanish physician Gaspar Casál, who called it mal de la rosa (disease of the red rash). In the intervening centuries, pellagra was particularly widespread — and well documented — in northern Italy, with cases reported as far afield as South Africa and Egypt. The U.S., historically, had seen few cases. Clearly, something had changed. But what?

One of the first doctors who made the connection to pellagra was James Babcock of the South Carolina State Hospital for the Insane. In 1908, he traveled to Italy and confirmed that he and his colleagues were right about the disease’s diagnosis. He went on to organize the first U.S. conferences on pellagra, where two competing theories on the disease’s cause went head to head.

One theory held that pellagra was an infectious disease carried by Simulium flies. “This was the golden era of the germ theory,” says University of South Carolina internal medicine and infectious disease specialist Charles Bryan, author of Asylum Doctor: James Woods Babcock and the Red Plague of Pellagra. Yellow fever, malaria and Rocky Mountain spotted fever all had been proven in recent years to have an insect vector. Why not pellagra?

The other leading theory — originating back with Casál himself — suggested that corn, of all things, was to blame. Some proponents regarded only spoiled corn as the culprit. Others, including Casál, focused on the corn-based diet common among impoverished victims, and advocated treating pellagrins (those suffering from the disease) with a more varied diet.

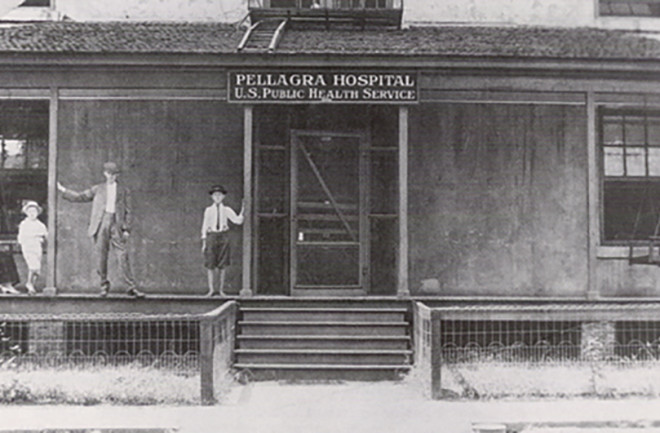

The U.S. Public Health and Marine Hospital Service — soon to be known as the Public Health Service (PHS), a precursor to the National Institutes of Health — began studying pellagra in 1909. But as the illness spread — South Carolina alone reported 30,000 cases by 1912 — Surgeon General Rupert Blue felt increasing pressure to escalate PHS efforts. In 1914, he assigned the PHS pellagra studies to Joseph Goldberger.

Goldberger's Crusade

A Jewish doctor from New York who’d emigrated from Hungary might seem an odd pick to lead a Southern campaign, but it did make sense. “In many ways, Goldberger was the perfect choice,” says American University historian Alan Kraut, author of Goldberger’s War: The Life and Work of a Public Health Crusader. “He had experience as an epidemic fighter on malaria, typhoid and dengue fever, and on yellow fever in the South. He was married to a Southern woman. And he had lots of lab experience.”

Right away, Goldberger saw a flaw in the fly-infection theory: Institutions with pellagra cases consistently reported that staff members, presumably vulnerable to the same flies, weren’t diagnosed with the disease. The recent identification of diseases caused by dietary deficiencies further convinced Goldberger that a corn-based diet could be pellagra’s cause.

The grain had only recently become a popular foodstuff. As “King Cotton” and textile mills came to dominate the South’s post-Civil War economy, many families converted all their farmland to cotton. They stopped planting vegetables and keeping livestock. As a result, many poor Southerners now ate almost exclusively what was called the three Ms: low-quality meat, molasses and meal (industrially refined cornmeal) — the same cheap gruel often served at orphanages and asylums. Pellagra was most widespread among populations subsisting on the three Ms.

To test his diet theory, Goldberger supplied what he called “a diet such as that enjoyed by well-to-do people” — meat, milk and vegetables — to two Mississippi orphanages and an asylum. Pellagra rates there plummeted. His next quest: to induce pellagra in healthy subjects. In 1915, with pardons in hand from Mississippi’s progressive governor, Goldberger recruited 12 healthy volunteers at the Rankin State Prison Farm to eat the three Ms diet. Within the six-month trial period, six volunteers exhibited the telltale dermatitis. Goldberger was convinced he had proven the link between the Southern poverty diet and pellagra.

To bolster his case against the germ theorists, in 1916 Goldberger conducted what he called filth parties. He tried to infect himself, his wife and other volunteers with pellagra by injecting and ingesting the skin scales, urine, feces, blood and saliva from pellagra patients. No one got pellagra. He also organized extensive epidemiological studies of seven villages that conclusively proved the link between pellagra and poverty. The studies are still used in medical schools today and hailed for their thorough, groundbreaking analysis of where economics, social conditions and health intersect.

Yet pellagra raged on, propelled by plummeting cotton prices in 1920. Goldberger advocated for food aid for the South, to mitigate what the PHS called a “veritable famine” developing in the Cotton Belt due to poor farmers’ diets. Southern politicians and businessmen railed against the recommendation, which they perceived as an attack on their honor. “Goldberger didn’t understand Southern pride,” Kraut says. “His mission was to conquer the suffering and solve the medical mystery.” He still had a ways to go.

The P-P Factor

Goldberger focused on identifying the missing dietary element, which he called the P-P factor, for pellagra preventive. In 1922, he tried to induce black-tongue disease — the canine analog of pellagra — in his laboratory dogs by feeding them a diet typical of poor Southerners, plus brewer’s yeast purely to stimulate the dogs’ appetite. The dogs remained healthy, prompting suspicion. Without the yeast, the dogs developed pellagra. Repeated testing on the dogs, then on human subjects, confirmed that brewer’s yeast, a product the poor could afford, contained the P-P factor that cured and prevented pellagra.

Goldberger was finally publicly vindicated in 1927. That spring, the Mississippi River flooded, to devastating effect. The potential for a widespread pellagra outbreak surged in flood-ravaged areas of Tennessee, Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi. Goldberger oversaw the Red Cross’ distribution of 12,000 pounds of brewer’s yeast in those areas. That effort cured most pellagrins within six to 10 weeks, prevented untold thousands more cases and earned Goldberger the recognition that was long overdue — though he wouldn’t enjoy it for long.

Goldberger died in 1929, the same year that pellagra cases at large started declining. The Red Cross carried on his work; by 1937 it had distributed 500,000 pounds of brewer’s yeast — frequently referred to as Vitamin G for Goldberger. That year, researchers identified niacin (abundant in brewer’s yeast) as the elusive P-P factor, and doctors established a standard dosage and therapy. Niacin has since become a dietary staple, now better known for fighting high cholesterol than pellagra.

Today, pellagra is mostly relegated to history lessons and medical reference books. But occasionally, such as during isolated outbreaks in a refugee crisis, the world receives a vivid reminder of how the disease still affects people. And as Tissier saw in her hamsters, it’s also a lesson anyone caring for animals should keep in mind. This scourge is not gone, just largely forgotten.