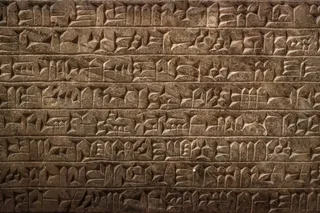

We don’t know how language first began. The first writing didn’t occur until around 3200 B.C.E., and we know that spoken language came before that. Some experts contend that it started with hand gestures along with sounds and signals that, in short order, gave humans a leg up when it came to survival.

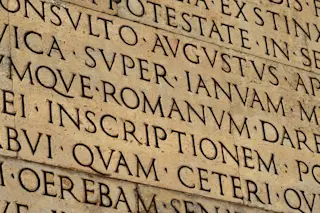

Fast forward a few thousand years, and the ancients were steeped in it. The Ancient Greeks, for example, were known for their linguistic achievement. By this time, an abundance of languages would have existed and been spoken throughout Greece and around the world.

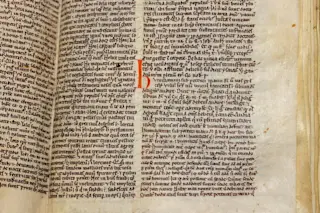

But if there wasn't a language in common, ancient people would have turned to an interpreter. Translation in ancient societies wasn’t as formal as it is today, and interpreters who could speak Greek, Latin, Persian, Coptic, and Arabic, to name a few, would have had to mediate across cultures at trade routes or on ...