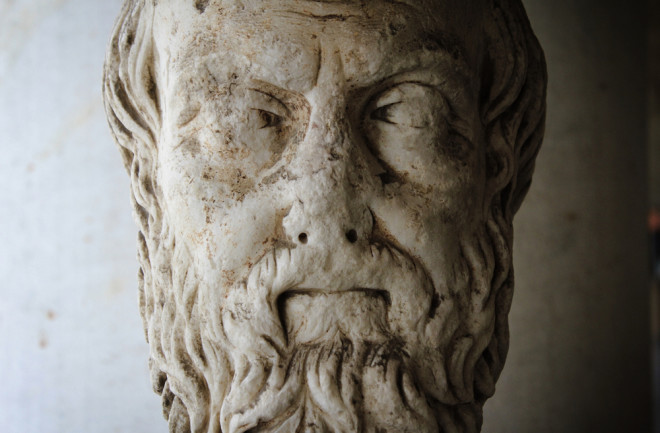

There are two ways to look at the question of who invented history. The first, of course, is that no one invented it; History is simply the result of the slow unfurling of time and the actions of those who have lived and died within its murky eddies. But the study of those actions, which we also call history, has a more definite beginning. For many of us in the Western world today, it began with a man named Herodotus.

Called “the father of history” by the Roman statesman Cicero, Herodotus is the author of the first authoritative historical text of any length. The Histories is a multi-volume account of the Greco-Persian wars, filled with informative digressions that span from Egypt to the near East. (It also gave us very the word history, which meant inquiry in the original Greek). To this day, Herodotus is often cited by scholars as a source of information on the lands and civilizations of his time.

Of course, Herodotus wasn’t quite a historian as we might think of today. His account, which relied largely on oral sources and second-person retellings, is replete with instances of fantasy. His tendency toward credulousness also earned him the somewhat less flattering appellation, “father of lies,” based on the numerous critiques of his work that began shortly after The Histories was published.

Herodotus was not the first to write down history. Greeks before him, notably Hecataeus of Miletus, had also written down their accounts of historical events. But no one before Herodotus had attempted to compile the kind of comprehensive record of a major historical occurrences that The Histories represents. Through it, Herodotus attempts to show not just what happened, but why, scholars say.

The First Historian

Of Herodotus the man, little is known. He was born in the city of Helicarnassus, in modern-day Turkey, and which was then part of the Persian empire. He traveled widely, even as a relatively young man, venturing to Egypt, and then moving to Athens. Herodotus reportedly visited parts of the Middle East, including Babylon and present-day Palestine and Syria, as well as Macedonia and eastern Europe, reaching the Black Sea and the Danube River.

Along the way, he gathered interviews from locals, collecting their accounts of their own histories and of the more far-flung people they encountered. Herodotus was a curious man: He writes of his attempts to explain the seasonal flooding of the Nile, and to trace the lineage of the Greek gods back to ancient Egypt, among other things. He also probably gave oral performances of portions of his historical writings to public audiences in Greece, a common practice at the time.

Herodotus’ practice was often simply to write down everything he was told, and at times qualifying the accounts with his own observations. This habit may be part of the reason Herodotus has often been criticized of outright confabulation. We hear of headless men with eyes in their chests in Libya and gold-digging ants in India that are larger than a fox (now thought to be marmots). It’s unclear whether Herodotus meant to portray these stories as truth, or if he simply intended to catalogue what he had been told by various people as he traveled.

For these reasons and others, Herodotus’ writings drew heavy criticism in ancient Greece. The historian Thucydides, who likely drew much inspiration from The Histories, took pains to call Herodotus out for what he perceived as inaccuracies and biases. And the Greek philosopher Plutarch, writing some three centuries later, mounts an even greater assault, arguing that Herodotus’ work was biased in favor of non-Greeks, and questioning the historian’s judgement. Today, scholars take a more balanced view of Herodotus the historian. Though his tales might not always be truthful, there is much that Herodotus got right — and his insights into the Greek world and beyond at the time are nearly unparalleled.

Occasional fantasies aside, Herodotus also reported on much that was true. Alongside the headless creatures, he writes of impalas, gazelles and elands in Africa, and of Ethiopians wrapped in lion skins with long bows made of palmwood. Environmental science and biology show up as well. Herodotus reported on the annual flooding of the Nile, and speculates on what caused it. He notes the astonishing growth of crocodiles: “No mortal creature of all which we know grows from so small a beginning to such greatness; for its eggs are not much bigger than goose eggs, and the young crocodile is of a proportional size, but it grows to a length of twenty-eight feet and more.”

A (Mostly) True Account

Herodotus took it upon himself to correct what he saw as the inaccuracies of writers before him. He offers a conflicting account of the events relayed by the epic poet Homer that began the now-legendary Trojan War. The war is supposed to have been instigated when a Trojan kidnapped Helen, wife of the Spartan king Menelaus. But Herodotus, based on research during his time in Egypt, dismisses this as mere myth; Helen was actually in Egypt the whole time, he counters, blown off course during a sea journey.

The Histories also contains what is likely the more accurate version of the legendary story of a lone runner delivering the news of the Greeks’ victory at the Battle of Marathon to Athens, before perishing of exhaustion. But Herodotus’ account instead involves a runner being sent from Athens to Sparta before the battle (a much larger distance of about 150 miles) to ask for help, and then the entire Athenian army marching back to Athens after the battle to confront a Persian fleet bearing down on the city.

But more modern historians have noted inconsistencies throughout Herodotus’ writings, that they say indicate he may never have visited some of the places he claims. For example, he never once mentions the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, despite having allegedly traveled there.

But Herodotus has been vindicated in other ways. For example, a boat recently unearthed in the Nile delta matches almost exactly his description of a curious kind of barge-like watercraft used there.

And his account of the Greco-Persian war, the main subject of The Histories, is also held to be largely true. To lay out the full story of the war, Herodotus begins much further back, describing the history of Persia, as well as Athens and Sparta, and the feats and follies of numerous royal characters along the way. Along with the geography and infrastructure of places he visits, Herodotus imparts numerous observations on the people and customs he encounters, or which he is told about along the way.

In this meandering way, Herodotus finally comes to a lengthy description of the various military engagements of the war itself, a decades-long conflict that would define the course of history during his lifetime and for decades afterward. That story alone would qualify his work as a valuable piece of historical writing — but it is the many and varied digressions he embarks upon that define the true value of The Histories today.

Herodotus gifts us with insights into the ancient civilizations of Egypt, Persia, Assyria, Scythia and more. Given his is one of the oldest works of prose in existence, The Histories is often scholars’ best source for accounts of these cultures, even 2,500 years after Herodotus' death. And beyond that, as many historians point out, it’s also just a really fun read.