Three quarks. Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Blogs by their nature do not go through the editing a writer comes to value before new assemblages of words are let out in the world. No matter how many times I reread and revise a post, I am chagrined how often I find, after pressing “publish,” that there is a typo or two. These are not actually random mistypings -- spellcheck usually spots those -- but neurological malfunctions. Bugs in the wetware. I will think one word and type another, and with each rereading my mind automatically sees what I intended and not what I typed. The wound heals over and the scab goes unnoticed. Until I press “publish” and the blunders jump out at me. A good editor can also protect you from worse sins -- errors of fact or logic -- and they can protect you from yourself. From those times you’re blinkered by your own slender wormhole or when you wander too far out on a rhetorical twig. After I began writing this, I came across this observation about blogs by Susan Orlean:

. . . you have no editor and no opportunity to have your work filtered through a critical eye. . . . somebody who says, ‘This doesn’t make sense to me,’ or, ‘Why are you writing this piece?’ or, ‘This lede just doesn’t engage me.’ A blog just doesn’t offer you that.

Making an error, large or small, and committing it to print -- that is one of the demons that tormented Murray Gell-Mann, and made it so difficult for him to write the papers that marked him as the greatest physicist of his generation. He described his fear at the beginning of his book, The Quark and the Jaguar, which I mentioned in my previous post.

Anyone who knows me [Gell-Mann wrote] is aware of my intolerance of mistakes, as manifested for example in my ceaseless editing of French, Italian, and Spanish words on American restaurant menus. When I come across an inaccuracy in a book written by somebody else, I become discouraged, wondering whether I can really learn something from an author who has already been proved wrong on at least one point. When the errors concern me or my work, I become furious. The reader of this volume can therefore readily imagine the agonies of embarrassment I am already enduring just through imagining dozens of serious mistakes being found by my friends and colleagues after publication and pointed out, whether gleefully or sorrowfully, to the perfectionist author.

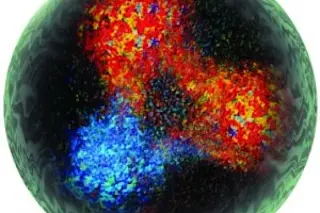

He recalled a story he once heard about a legendary lighthouse keeper, occupying his long, lonely nights by scouring books, one after the other, and noting each mistake. That erudite lighthouse keeper must have been beaming his beacon into Murray’s eyes when he was struggling to write his landmark paper about The Eightfold Way -- the periodic table that brought order to the seemingly haphazard realm of elementary particles like protons, neutrons, and mesons. He would submit the paper to Physical Review and then, after lying awake agonizing over the details, withdraw it from consideration. For a year he went back and forth, back and forth before finally letting go of the draft. It was rushed into print, and just in time, appearing in February 1962. The Israeli physicist Yuval Ne’eman had independently come up with the same idea. If Ne’eman’s paper hadn’t been bounced because of a formatting problem (his secretary didn’t double-space the manuscript) he would have beat Murray to the punch. Ne’eman got plenty of respect but Gell-Mann got the ownership every physicist craves. Two years later, in 1964, came his paper, "A Schematic Model of Baryons and Mesons," the one that was honored this week at Caltech. What had long been considered the most fundamental particles turned out to be glommed together from tinier things called quarks. But were they really things with a palpable existence or just numbers, a fancy kind of accounting device -- “a useful mathematical figment,” as Gell-Mann later put it? It was a question that bedeviled him and will be the subject here of a forthcoming post. Quarks were another idea independently and almost simultaneously discovered, this time by George Zweig. Gell-Mann’s earlier claim to fame, the discovery of what he called “strangeness,” was also arrived at by another theorist, Kazuhiko Nishijima. But no one shared Murray’s zest for evocative names -- quark, strangeness, Eightfold Way. And no one had lit upon three such powerful ideas. It was fitting that he alone was awarded, in 1969, the Nobel prize in physics. While I was writing Strange Beauty, I was lucky to be invited to a Nobel Prize ceremony and witness firsthand the lavish affair. This time Steven Chu, who later became Obama's Secretary of Energy, was one of the winners. But I wish I could have watched Murray at Stockholm. I was able to piece together the details of his experience through interviews and archival sources. Here is how I described it in Strange Beauty:

When the ceremony was over, the laureates and their families were packed into limousines and chauffeured across the river for the banquet at Sweden's architectural gem, the Town Hall. To the accompaniment of a chamber ensemble, the laureates filed into the elegant Golden Hall, with its 24-karat mosaics. In further keeping with the pre-eminence Nobel had given physics, Margaret, as wife of the sole winner of that year's prize, entered the hall on the arm of the king and sat by his side during the long dinner. Murray was wedged between the princess and the queen. After the toasts, course after course of lavish dishes were announced with musical fanfares, the army of waiters striding in formation to serve the food. Champagne (Krug brut reserve) was followed by an appetizer of avocado stuffed with salmon and then, for the main course, a roast filet of beef with truffles (Périgourdine style), served with a 1959 Bordeaux from Chateau Potensac. (But alas, no pheasant cooked between slices of veal.) Then with the orange sorbet and coffee and liquers, the after-dinner speeches began.

Murray charmed his hosts by launching into Swedish during his dinner talk, later beating himself up because he had mispronounced a word. Afterwards the fear of error probably contributed to his troubles in writing up his Nobel lecture for publication in the annual volume, Le Prix Nobel. This again is from Strange Beauty:

Seized with a pernicious case of writer's block, something that has plagued him all his life, he fended off one urgent telegram after another with abject apologies, finally conceding -- months after the deadline was extended again and again for his benefit -- that he wouldn't be submitting a lecture after all. Among the rows of volumes commemorating each year's prizes, one will find an empty page for Murray Gell-Mann.

Gell-Mann's Nobel citation didn't specifically mention quarks. It wasn't entirely clear yet that they existed. You may have been puzzled by an obscure aside in my description of the Nobel banquet -- "pheasant cooked between slices of veal" -- and that is part of the story, the one I'll tell next. Part 3: An Idea as Grand as the Ritz Part 1. My First Strange Encounter with Murray Gell-Mann Lighthouse keepers: Please report typos and other neurological glitches by email or through Twitter. @byGeorgeJohnson Related: Strange Beauty web page For a glimpse of my new book, The Cancer Chronicles, please see this website.