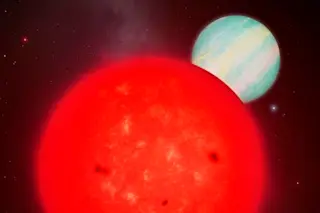

Ever since astronomers started finding planets orbiting other stars, they have been learning just how rich and peculiar the cosmos can be. The latest observations add yet another head-scratcher: giant gas planets that circle their stars on wildly tilted orbits or go around the wrong way altogether.

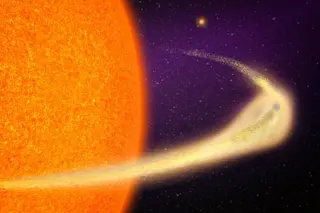

Current models suggest that planets should orbit in the same direction as their star’s rotation (as is true for our solar system), in keeping with the view that the whole shebang formed from the same spinning disk of material. One possible explanation for the newfound rebel planets is that they have been pulled out of their normal orbits by a nearby stellar companion to their central star. This deep-space billiards game is known as the Kozai mechanism.

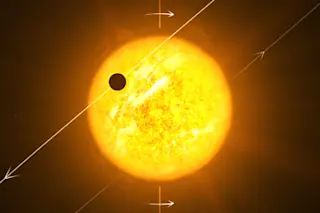

In this scenario, “you have a Jupiter-size planet making close passes to one of the stars in a binary system,” says Andrew Collier Cameron, an astronomer at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. The planet’s swooping flybys create tidal waves on the host star, which combine with the gravitational tug of its companion star to pull on the planet in unpredictable ways. “Its orbit flips essentially randomly relative to the orbital plane of its star,” Cameron says, potentially turning over completely. This process may be surprisingly common. Cameron and colleagues recently studied 27 exoplanets and found that one-third had highly tilted orbits, including at least four that orbited backward.

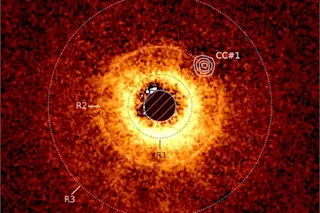

More oddball finds are probably on the way. Some exoplanets have long, cigar-shaped orbits. And researchers at the University of Texas just discovered a system in which two worlds orbit their star at a 30-degree angle to one another. Their rakish tilt may be the result of gravitational disturbances from a companion star, perhaps in combination with the influence of another planet that got tossed out of the system entirely. Fred C. Adams, an astrophysicist at the University of Michigan who studies planet formation, says such finds indicate we still don’t know the true variety of worlds out there: “Planets can wiggle around in a lot of ways.”