In 1978, utilities workers digging in Mexico City unearthed a colossal stone relief, depicting an unmistakable figure: the Aztec goddess Coyolxauhqui, naked, dismembered and decapitated, after being slain by her brother, Huitzilopochtli, the god of sun and war. Archaeologists realized the carving must be part of Templo Mayor, the Great Temple of the Aztec Empire, known to lie somewhere below the city center based on colonial-era accounts and previous limited digging projects.

The setting had deterred earlier archaeological investigation because the Aztec ruins were buried under functioning buildings, some erected in Spanish colonial times, themselves protected as historic landmarks. However, the Coyolxauhqui relief sparked such national excitement that archaeologists were permitted to embark on long-term excavations, first led by Eduardo Matos Moctezuma of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History.

The government initially allowed the team to demolish 13 buildings of limited historical value. Since then, excavations have continued in fits and starts, in collaboration with construction and maintenance projects. Today, remains of the main temple are exposed for visitors, right in the city center — a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

“It’s a beautiful, lively Mexican scene where you’ve got modern Mexico City, colonial Mexico City and also pre-Columbian Mexico,” says Davíd Carrasco, a scholar of Mesoamerican religions at Harvard University. The site is so rich that research could “go on for another 100 years,” says Carrasco, who studies the temple. Some recent spectacular finds follow.

FAST FACTS

1978: Accidental discovery by utilities workers kicks off modern excavations.

Time period of site: 1325-1521, during the rule of the Mexica Aztec.

Built by: The Mexica, the ethnic group that ruled the Aztec Empire — itself a coalition of peoples across Central America from the mid-1300s until the Spanish conquest began in 1519.

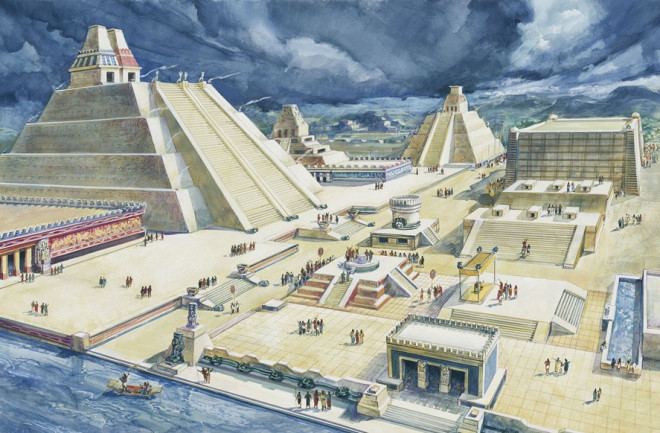

Location: Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, present-day Mexico City.

Excavations led by: Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History.