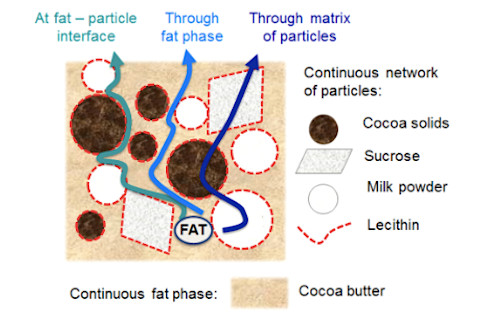

Is there anything more disappointing than finding a chocolate bar in the back of the desk drawer, anticipating a tasty treat, then unwrapping the bar only to find a dull, grey haze has overtaken your dear candy? Seeing as bloomed chocolate is still edible, yes, there are many things more disappointing than that. But surely you’re curious about how chocolate that was once shiny and perfect came to be filmy and rough. Chocolate blooming, the process that produces the white-grey film that appears on the surface of an old chocolate, is due to molecular migration. More specifically, this imperfection is caused by the movement of fats to the surface of the chocolate followed by a subsequent recrystallization. In a paper published by Applied Materials & Interfaces, a team of researchers dedicated to keeping our chocolates blemish-free has clarified the precise mechanisms that cause chocolate blooming. The main fat in chocolate is cocoa butter, which is solid at room temperature and melts at 37 degrees Celsius. The proportion of solid to liquid cocoa butter depends on the lipid composition, which depends on which specific triglycerides are present. The solid to liquid proportion also varies with the storage conditions of the chocolate. As proposed by Aguilera et al, scientists who study this chocolate blooming, consider chocolate as a particulate medium of fat-coated particles such as cocoa solids, sucrose, and milk powder, all suspended in a fat phase with the aid of an emulsifier, which helps to mix fats and oils with water, which usually repel each other. There are six crystallographic polymorphs of cocoa butter molecules, that is, there are six ways the molecules can organize themselves. The structural stability of these polymorphs increases from 1- 6; form 1 is the best at forming solid butter at room temperature, while form 6 tends to arrange in the loose bonds of a liquid. Form 5 is the main form in chocolate, as it possesses the most aesthetically desirable properties. While the phenomenon of blooming is well known to result from melting and recrystallization of chocolate into a less desirable polymorph, it has been unclear how fat moves through the chocolate particle network: Does it move along the fat-particle interface? Does it diffuse through the fat phase (cocoa butter), or through the matrix of assorted particles?

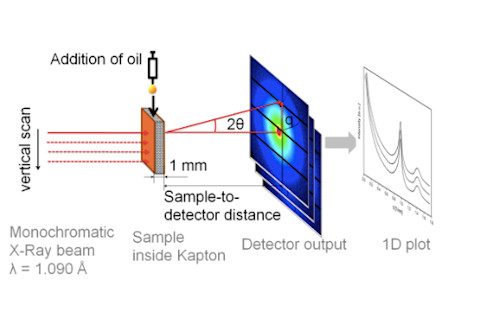

Possible lipid migration pathways in chocolate - Reinke et al In this experiment, researchers used synchrotron microfocus small-angle X-ray scattering to determine the preferential migration pathway of the cocoa butter molecules surrounded by three different soild components (cocoa solids, skim milk, and sucrose). This technique allows researchers to record the scattering of x-rays through a sample with defects in the nanometer range. They can then extrapolate information about the material’s macromolecules, their shapes and sizes up to 125 nanometers, and distances between partially ordered materials, such as pore sizes. For this experiment, this method is better than more traditional macroscopic techniques as the sample does not need to be dissected in order to examine it, therefore the same sample can be continually analyzed.

Sketch of the experimental setup - Reink et al The researchers prepared and tempered four different chocolate samples. An initial scattering of x-rays and data collection was performed before the addition of sunflower oil, then 10 uL of oil was pipetted onto the chocolate surface, and a second scan was performed. Images of the droplet were captured through a high-speed camera. These scans were repeated at 5, 10, and 30 minutes after oil addition, and again after 1, 2, 5, and 24 hours. The results obtained suggest that oil is migrating through pores and cracks in the solid structure driven by capillarity within seconds. This means that the oil can flow in narrow spaces in opposition to gravity. Then chemical migration through the fat phase occurs. The oil doesn’t traverse the fat-particle interface, nor does it move through the matrix of solid particles. This migration disrupts the crystalline cocoa butter, which induces softening. Because the most immediate migration of oils occurs through the material porous structure, the formation of chocolate bloom could be prevented by minimizing pores and defects in the chocolate matrix. To prevent the longer-term effects of chemical migration of lipids, one must minimize the content of non-crystallized liquid cocoa butter. Tempering chocolate lends to crystalline structures that resist migration, as will reducing the liquid fat content. However, to ensure that you never encounter a sad hazy chocolate again, we recommend eating all chocolate goods expeditiously. Works Cited

Tracking Structural Changes in Lipid-based Multicomponent Food Materials due to Oil Migration by Microfocus Small-Angle X-ray Scattering. Svenja K. Reinke, Stephan V. Roth, Gonzalo Santoro, Josélio Vieira, Stefan Heinrich, and Stefan Palzer. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2015 7 (18), 9929-9936. DOI:10.1021/acsami.5b02092

Aguilera, J. M.; Michel, M.; Mayor, G.Fat Migration in Chocolate: Diffusion or Capillary Flow in a Particulate Solid?—A Hypothesis PaperJ. Food Sci. 2004, 69, 167–174

Elsbeth Sites received her B.S. in Biology at UCLA. Her addiction to the Food Network has developed into a love of learning about the science behind food. Read more by Elsbeth Sites

About the author: