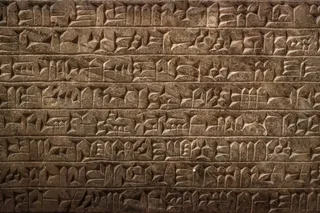

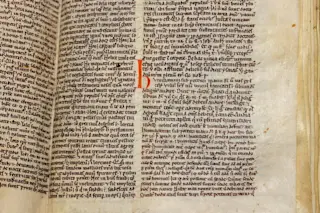

One of the things I like about the Stargate franchise is that it shows the characters working to understand things, often over a course of episodes or even seasons, instead of just magically knowing it all--for example, it took a long time for the franchise to go from a few captured enemy spacecraft, through some buggy hybrids, plus a hefty technology transfer from a friendly civilization, to the human-built heavy cruisers like the Deadulus. This "show your work" style comes right from the 1994 movie that started it all, where archeologist Daniel Jackson was brought in to figure out the mysterious inscriptions on the first discovered stargate. So it was a return to the franchise's roots in more ways than one when Jackson made a guest appearance in Atlantis, looking for a long lost laboratory somewhere in the city. This required some old fashioned detective work, pouring over old records ...

Stargate Atlantis: Why Curators Could Save The Galaxy

Explore how the Stargate franchise masterfully portrays characters' detective work in science and the significance of curatorial arts.

More on Discover

Stay Curious

SubscribeTo The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Subscribe