A mainstay of the December night sky, the Geminids meteor shower first appeared in the mid-1800s, and it’s grown more impressive in the ensuing years. It now features up to 120 meteorites an hour given clear skies.

A new study may have found that the shower originated in some type of catastrophic collision. This differentiates it from most showers, which come from icy comets that pass close to the sun, that then melts and releases particles.

Read More: The Asteroids We Should Watch Out For

An Asteroid or a Comet?

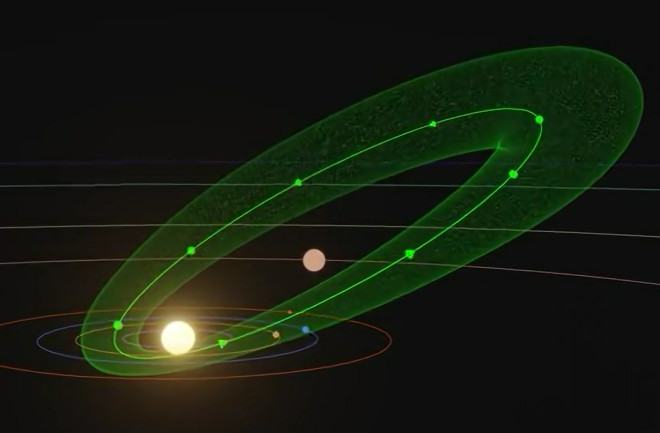

The study concludes that instead of a comet, the Geminids material came from a small asteroid, 3200 Phaethon, which is only about 4 miles in diameter. Named after the driver of the Greek god Helios’ chariot, 3200 Phaethon passes close to the sun on its way around an uneven orbit. The material follows a similar orbit, although it stays just to the outside of the asteroid’s path.

Other researchers have suggested that it’s actually a dead comet that has lost all its ice, but the new team from Princeton argues that data from the Parker Solar Probe contradicts this. Parker launched in 2018 and now flies in an orbit around the sun, following a course that also allows it to gather data on dust clouds in the inner solar system.

The new study devised three models to test the origins of the Geminids meteor shower, using the Parker data. The first gave the broken-off material zero velocity relative to the asteroid. The second assumed that it had ejected at a velocity of up to one kilometer per hour, creating a different cloud.

The last model simulated that 3200 Phaethon was a comet, but the resulting orbit matched the Parker data the least. The second, most violent model matched the best and indicated a high-speed collision with another body, or potentially a gaseous explosion.

The Continuing Mystery of the Geminids

“Most meteoroid streams are formed via a cometary mechanism,” says Wolf Cukier, an undergraduate at Princeton and lead author on the paper, in a press release. “It’s unusual that this one seems to be from an asteroid.”

Parker also found, however, that some of the asteroid’s material does come from heat, as if it were a comet.

“What’s really weird is that we know that 3200 Phaethon is an asteroid, but as it flies by the Sun, it seems to have some kind of temperature-driven activity,” says Szalay. “Most asteroids don’t do that.”

The showers happen yearly when Earth’s orbit intersects with that of 3200 Phaethon’s material.

Read More: Thousands Of Meteorites Hit Earth Each Year — Here's What They Bring