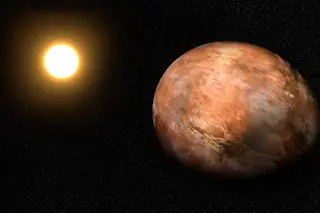

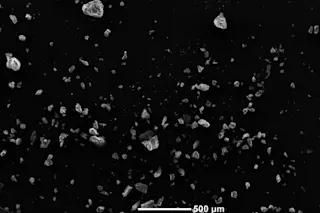

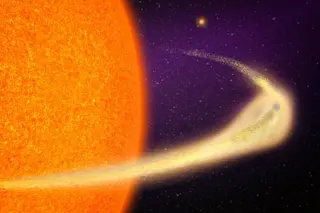

The target is 230 million miles away and 22 miles long. It is an asteroid, and NASA plans to put a spacecraft in orbit around it.

When the Mars Observer vanished last August, many planetary scientists regretted the all-or-nothing design of the billion-dollar spacecraft. Had its many instrument packages been carried separately by smaller, cheaper probes, researchers might now be poring over Martian photos instead of pining for a replacement mission. In that respect, at least, NASA has heard its many critics: its new program of unmanned space exploration calls for a series of low-cost, unmanned probes with tightly focused goals.

But low-cost does not necessarily mean low-risk or technically routine. On the contrary, in the first of these new missions NASA is going for something completely different: it plans to send a spacecraft to an asteroid--not just for a quick flyby, which the Galileo probe has already done, but ...