To determine trends in trade and cultural exchange, sometimes historians must follow the money. A team did just that by showing that Byzantine silver found its way into Anglo Saxon coins by A.D. 700, according to an article in Antiquities.

Historians had known for decades that, from around A.D. 660 to 750, Anglo-Saxon England saw a surge in silver coins, after the area had long relied on gold. But from where the silver had entered the currency stream remained a mystery.

Now a team of researchers from the Universities of Cambridge, Oxford and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam have cracked the case by analyzing the chemical makeup of coins held by the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

Money Mystery

Rory Naismith, a history professor at the University of Cambridge, had had an earlier theory about the coins’ provenance. “I proposed Byzantine origins a decade ago but couldn’t prove it,” Naismath says.

Naismath knew that there had been an “explosion” in trade and urbanization over that time period. Other researchers had focused on tracking silver from central and western France, so he followed his Byzantine hunch.

Both proximity and providence played a role. The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge had a collection of coins literally a few hundred yards away. And a new technique — portable laser ablation — had been developed. That technique allows researchers to investigate the chemical composition of a sample beyond just the surface. It also “captures” information about trace elements’ isotopes — radiological “tags” that can help pinpoint minerals to the areas they were mined.

Naismith partnered with Stephen Merkel from the University of Amsterdam, who had access to a portable laser ablation machine. Naismath was excited about using the new technique, because earlier methods, like X-ray fluorescence, could only examine a coin’s surface.

“Surfaces can be contaminated,” Naismith says. They could literally send a researcher to look at the wrong mine for the silver’s origin.

Read More: Who Invented Money and What Is the World's Oldest Currency?

Digging into Coins

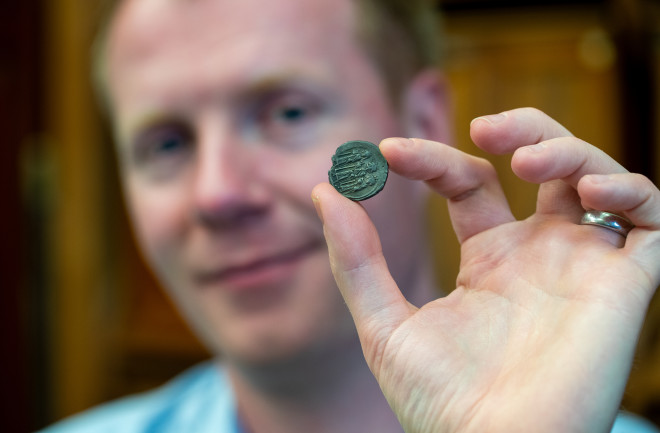

The laser method is minimally invasive, because it makes a minute mark on the coin where the laser “zaps” it.

“It is digging into the coin, but it's doing so on a level that is invisible to the naked eye,” Naismith says.

The group could take multiple readings of 49 of the 51 coins available. About half the coins were similar in content — hinting that they probably came from the same region.

“That was one thing that surprised us,” Naismith says. “There was not nearly as much variation between them in terms of lead isotopes or in terms of trace elements as we expected.”

In those 29 coins, the researchers found a clear chemical and isotopic signature that matched third to early seventh century silver from the Byzantine Empire in the eastern Mediterranean. The remaining coins contained a different mix of metals. Tests showed lower levels of silver, as well as small amounts of gold. That composition is consistent with silver mined at Melle in western France.

Exactly how and when the Byzantine and French silver were transformed into English coins is unclear. Naismith suspects the silver was first contained in objects held by the upper class, melted down when economic times got tough. But that is another mystery for the historians to solve.

Read More: How Money Has Changed Throughout History

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review them for accuracy and trustworthiness. Review the sources used below for this article:

Rory Naismith. History professor at the University of Cambridge

Stephen Merkel. Research Associate and Earth Science faculty at the University of Amsterdam