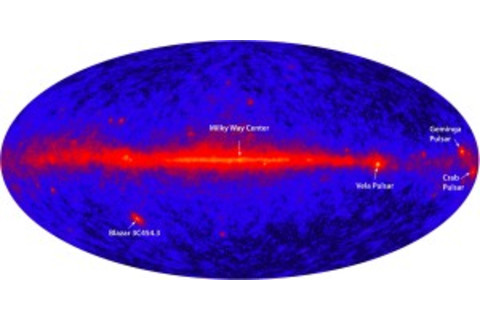

I just got back from the Cosmo-08 conference in Madison, which was great fun (and I'm sorry I had to miss the last couple of days). But just because I'm traveling, doesn't mean that science stops happening. It just means I might be late in blogging about it, if I were moved to do so, which in this case I am. The big news is that the Gamma-Ray Large Area Space Telescope, a satellite observatory launched back in June, reached two milestones: (1) it got a name change, from GLAST to the Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope (on the theory that not enough things are named after Fermi), and (2) they released the first new picture of the gamma-ray sky! And here it is; click for higher resolution.

You can clearly see the Galactic plane, of course, as well as a few objects that shine brightly in gamma-rays -- a handful of pulsars, and one distant blazar. [strike]GLAST[/strike] Fermi will be cranking out the science over the next several years, from down-and-dirty astrophysics to searches for annihilating dark matter. See Andrew Jaffe, Phil Plait, and symmetry breaking. Meanwhile, some of the folks who brought you the Bullet Cluster have now come up with MACSJ0025.4-1222 (or MAC-Daddy-J, as pundits have suggested).

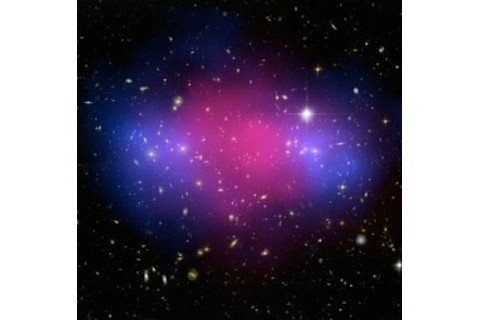

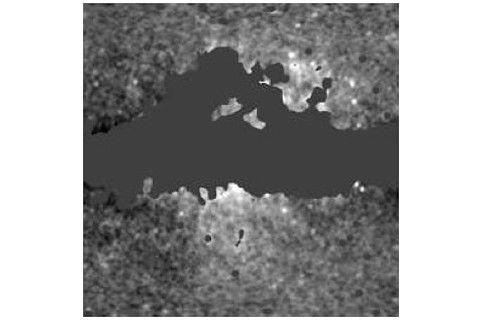

It's a similar story -- two giant clusters of galaxies smacked into each other, allowing their dark matter to separate from the hot ordinary matter in between. Gravitational lensing lets you figure out where the dark matter is, while X-ray observations reveal the ordinary matter. The Bullet Cluster was pretty darn convincing, but it's a scientific truism that nothing ever happens just once, so it's nice to see that magic repeated. Finally, I wanted to mention something that is somewhat old news, but that somehow had escaped my attention until Dan Hooper's nice talk at Cosmo-08. That is the WMAP Haze, a phenomenon originally noticed by Douglas Finkbeiner. The WMAP satellite, trying to observe primordial temperature perturbations in the cosmic microwave background, measures several different frequencies, to help correct for foregrounds. The CMB isn't the only thing that emits microwaves, but nearby dusty astrophysical sources generally depend on frequency in different ways, so one can try to remove their effects by seeing how the maps at different frequencies compare with each other. Some people, apparently, are actually interested in those dusty foregrounds, so they try not only to remove them, but to understand them. And Finkbeiner claims that when we remove all of the foregrounds that we know how to explain, and mask out the parts of the galaxy that are simply too bright to deal with, we are left with this:

There is some mysterious emission near the center of the galaxy, dubbed the "WMAP haze." There is an explanation on the market, which is what Hooper's talk was about -- the haze could come indirectly from dark matter! Dark matter particles annihilate, so this story goes, giving off a bunch of lighter particles, including electrons and positrons. These electrons and positrons swirl around in the galactic magnetic field, giving off synchrotron radiation, which is what we see as the haze. True? Plausible? Crazy? I don't know. The good news is that the dark matter model required to make it work is not thrown together just to fit this result -- it's a fairly vanilla model of weakly-interacting massive particles. The bad news is that it's hard to understand these dusty foregrounds, and difficult to be sure that you've accounted for all of the mundane ones. The great news is that this is exactly the kind of thing that [strike]GLAST[/strike] Fermi will test, by looking for the high-energy gamma rays that should also be emitted by annihilating dark matter. So stay tuned for some possibly exciting dark matter news, right around the corner.