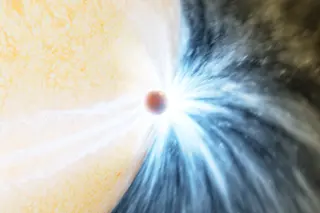

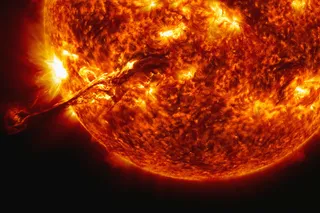

For the first time, astronomers have observed a star engulfing a planet, tearing it apart in a preview of what will happen to the Earth in about 5 billion years when the sun swells to its red giant phase. Discovery of the collision, which took place 12,000 light years away, could lead to a better understanding of the chemical makeup of exoplanets.

Space scientists had long assumed that such epic events take place and had even noticed a dearth of close planets in old star systems with larger stars, according to the new paper. Still, they didn’t know for sure what such a cataclysm would look like through a telescope.

Kishalay De, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, found the first evidence by accident, while sifting through data from the Zwicky Transient Facility, part of the Palomar Observatory in California. Every 48 hours, a camera connected to a telescope there surveys the stars, looking for those that have changed brightness during a short period of time. Normally, this is used to pinpoint supernovae, gamma ray bursts and other high-energy events.

Read More: How Many Ways Can the Sun Kill Us?

Looking for Stellar Phenomena

De had set out to find evidence of stellar binaries trading material when he came across a curious signal.

“I noticed a star that brightened by a factor of 100 over the course of a week, out of nowhere,” De told MIT News. “It was unlike any stellar outburst I had seen in my life.”

To investigate the strange object, he checked how it appeared in data from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, which takes spectroscopic measurements that reveal the chemical composition of a light source. The outburst came from a strange array of cooler molecules, not the helium and hydrogen spewed by binary stars.

Such molecules form in very cold stars, and their appearance here, in a hot, brightening star, puzzled De.

The Star that Swallowed a Planet

Along with some colleagues, he reviewed more data on the outburst, from an infrared camera at Palomar, which showed the sheer volume of the cool molecules. After some consideration, they later concluded that during the initial outburst, which had lasted about 25 days, the star had engulfed a planet up to 10 times the mass of Jupiter. From there, the outburst had faded over about 6 months and continued to reflect the presence of the unexpected molecules.

According to MIT, the energy amounted to a kind of stellar belch of gas that drifted from the star and cooled. That material came from the planet itself, which likely passed through the star’s outer photosphere before falling to its demise.

The star began swelling just a few months prior, according to Physics, as it began to run out of fuel, and merging with the planet only accelerated the process.

In the Distant Future

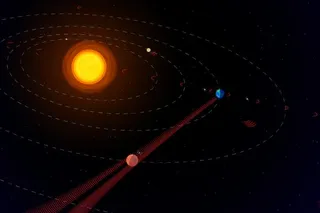

One day, billions of years from now, earth will fall into the sun, along with inner planets Mercury, Venus and Mars, possibly causing the star to swell further. (Technically, the earth is falling towards the sun right now, but because we’re in a stable orbit, we keep missing it.)

De and other researchers plan to collect more data on the star-eating event, which opened a special window into exoplanet makeup.

Read More: What Happens When a Star Dies?