Some of the world's oldest and most beloved toys are built on simple physics. A top, for instance, is ruled by gyroscopic stability and precession. Likewise, a yo-yo depends on momentum and acceleration, and building blocks on friction and compression. Now three toy designers have added more physics to these classics, giving them a brand new look.

"You want about a seventh of the weight of the yo-yo to be the weight of the die," says Steve Brown, Freehand yo-yo inventor. Courtesy of Duncan Toys

With multiple axes of spin, Tetratops twirl on any of their outside spheres. And all sizes stack together because three touching spheres form a stable triangle.

Steve Brown: Yo-Yo MasterTrying to do a release move with a yo-yo, such as going around the leg, is a fancy trick that confounds even experts. The toy's string is so thin and limp that it's hard to recatch. "I thought, 'There's got to be a better way to do this,' " says Brown. "I had a long wallet chain with two casino dice on it, so I pulled one of them off and threaded it onto the string. I realized that if you have enough of a counterweight on the end of the string, you can release the entire thing straight up into the air and then catch it again, and the extra weight at the end holds the string tight enough so that it doesn't wind up."

Sounds simple, but it took a year of work to get the design right. "It's one thing when you're sitting there with glue and felt and linen binding tape and all this lube and junk, and just jamming it into your yo-yo and messing around with it and getting one to work," says Brown. "It's another thing entirely to figure out how to do it so it plays consistently the same way every time." The biggest problem: figuring out the weights of the yo-yo and the die. The perfect matchup: a 10-gram die with a 65-gram yo-yo. The die weight is crucial because it dictates speed, explains Brown. "If you throw a 'man on a trapeze' move, you want the momentum of the yo-yo hitting the string to carry the die all the way around. If the die is too heavy, there won't be enough force from the yo-yo, so it will get about three quarters of the way around and drop, and probably smack you in the knuckles. If it's too light, it's going to shoot around so fast that you're not going to be able to track it, and it's going to smack you in the knuckles. So it becomes very important to your knuckles to have the die the right weight."

The added range of the Freehand yo-yo ($14.95; Duncan Toys, www.yo-yo.com) makes it a sort of hybrid between yo-yoing and juggling, and Brown expects that will bring players new respect. "One of the reasons that yo-yos have never gone over well as a performer's prop is that there's no risk because it's tied to your hand. So when it's not, all of the sudden the audience realizes he could drop it, he could shoot it off into the crowd, he could smack himself in the head. You've got that 'fear of failure' factor going, so that when you do pull something off, it's 10 times more impressive."

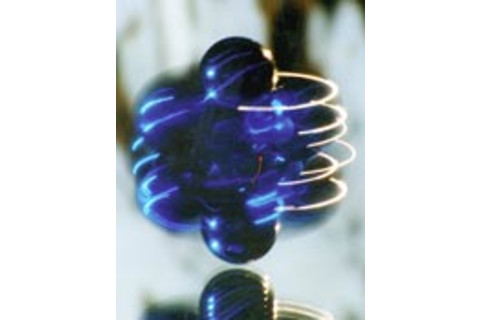

Kurt Przybilla: Spin DoctorFor years, Przybilla has been obsessed with the complex geometric structures of architect-inventor Buckminster Fuller. To better visualize Fuller's designs, Przybilla built stick models of multisided figures, like tetrahedrons (which have four faces) and icosahedrons (20 faces). He was stumped, however, when it came to modeling Fuller's drawings of spheres packed into such polyhedral shapes. Then he visited an industrial plastics store and discovered acrylic spheres. "I took them home and glued them together," says Przybilla. He played with stacking up the polyhedrons until "one day a stack fell over and one of the polyhedrons spun a bit. So I gave it a spin, and it kept going. I immediately had to try all of the different shapes. They all spun." Most surprising of all, unlike the traditional top, which has only one axis of spin, Przybilla's polyhedrons twirled on any of their outside spheres.

"My goal is for everyone to know what a tetrahedron is, like they know what a cube is," says Tetratops designer Kurt Przybilla.

A Tetratop in mid-spin. The tops will spin on any of their outer spheres.

Thus was born Tetratops, the first top with multiple axes of spin ($7.99 for two small tops with trading cards and booklet, $16.95 for the one-top deluxe set, at www.tetratops.com. Licensed to Duncan Toys, www.yo-yo.com). The tetrahedron has four axes of spin, an octahedron three, and an icosahedron and cubeoctahedron six. "Hopefully the tops will introduce people to another dimension, and they will realize a lot more about the nature of things," says Przybilla. For example, a diamond's atomic bonds form a tetrahedron, while soccer balls and carbon 60 molecules -- buckyballs -- are truncated icosahedrons. "Bucky always called these shapes the primary structural systems of the universe," Przybilla says. Stack the octahedrons and you get a double-helix like that of DNA. In fact, all the tops stack, because "even though the spheres are different sizes, the angle at which they relate to each other is the same."

Przybilla wondered if Fuller would have been surprised by the discovery. "I've seen a photo of Bucky with a full set of acrylic models like this. I met Bucky's daughter last summer, and I asked her, 'Did Bucky spin these?' I had to know, because he talks a lot about spin in systems and precession but he doesn't ever mention spinning tops. She said 'I don't remember him ever spinning one.' She was very happy I was spinning them."

Chuck Hoberman: Shape-shifterHoberman is best known for his plastic expanding and contracting geometric figures, especially the Hoberman Sphere, which smoothly alters its shape with just a tug of a finger. To please fans who want to create structures from scratch, two years ago Hoberman came out with Expandagon, a building set made up of link-together expandable squares and triangles. This September, Hoberman will introduce Gro-bots, a new line of playthings that supplies even greater creative thrills. With the first two kits, people can link up the intricate pieces and connect them to a remote-control-operated motorized square to produce a shape-shifting robotic "Hornet" or "Hopper."

"The design that interests me is bottom up," says Chuck Hoberman, inventor of Gro-bots. "When you hook the kit pieces together, you don't quite know what you're going to get."

The unfolding shapes, Hoberman says, work as a hybrid between static structures, which resist applied forces and hold their form, and mechanisms, which translate the force into movement. "In an ideal version, you would be pounding on the thing with all your might and it wouldn't budge," he says. "You need to apply force just the right way, and then it moves smoothly and beautifully."

That quality, says Hoberman, stems from the complexity of the parts. "Each square has 44 pieces of plastic in it. The sheer number of pieces moving together makes the transformation happen, and that's where the surprise comes from. You begin to look at it more like a living thing than just a mechanical thing. Some artificial intelligence people will say that we're just made up of billions of little mechanical things that add up to something that looks a lot like we're conscious."

Hoberman's Gro-bots (Hopper, $20, and Hornet, $30, www.hoberman.com) have taken on forms that surprise even him. "When we got the first pieces," he says, "my team and I defined 'legal' and 'illegal' connections, in the sense that a link would work one way and not the other. But we've realized that the illegal connections are often the most interesting. And shapes where half the connections are legal and half illegal may have a much more organic quality; they can expand on one side but remain contracted on the other, and then reverse. You begin to imagine that what you're really doing is creating behaviors: walking, oozing, and morphing."

Activate the Gro-bot Hornet's motor and its body expands, putting stress on the legs until they thrust outward, making the "insect" lurch forward.

Museums

The Good SeedIowa's Heritage Farm preserves genetic diversity

By Judith Kirkwood

At first glance, the 173-acre spread near Decorah, Iowa, looks like an upscale version of one of those pick-your-own-produce farms. On a bright summer day, the fields are lush with tomatoes, beans, and lettuce, and in the orchard, apples dangle from tree branches. Look more closely— and read the signs— and you'll see that these fruits and vegetables are unlike anything you'll find in even the fanciest specialty markets. There's the Bird Egg Bean that was brought to Missouri in a covered wagon in 1859 by the grandparents of Lina Sisco, the Plum Lemon Tomato collected from an elderly seedsman in Moscow's Bird Market, and a lettuce that Thomas Jefferson grew at Monticello.

This is Heritage Farm, headquarters of Seed Savers Exchange (www.seedsavers.org), the nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving "heirloom" crops. Here, where visitors are welcome Memorial Day through September, seeds from vegetables, fruits, herbs, and flowers, many of them carried by immigrants from their homelands, are being grown and collected in an ambitious effort to rescue hundreds of varieties of plants from extinction. Why the fuss over these rarities when most grocery stores today boast enormous selections of produce, from alligator pears to baby zucchini, as well as multiple varieties of a single fruit or vegetable? At my local market, I can get 10 different types of apples. Still, that is a far cry from the 7,000 varieties available a century ago; now only 700 exist. Other fruits and vegetables have been similarly decimated, thanks mainly to agrochemical conglomerates replacing regionally adapted plants with hybrids and patented varieties that withstand mechanical picking and cross-country shipping.

The result is a loss of genetic diversity, not to mention taste, and that does not bode well in an era of rapid climate change and pesticide-resistant insects. "The food crops that exist right now are all of the plant material we're ever going to have to breed the food crops of the future," says Kent Whealy, who with his wife, Diane, founded Seed Savers in 1975. In the past, scientists have been able to overcome crop diseases by utilizing hardier, older strains of plants. "But if this material dies out, there is no assurance we can do that in the future," he says. By maintaining more than 18,000 varieties of seeds in storage vaults, Heritage Farm is preserving what might save us after another potato famine or corn-blight disaster. At the least, the seed selection offers plants that can survive drought or thrive in clay soil or fend off the two-spotted spider mite.

Books

Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color That Changed the World

Simon Garfield W.W. Norton & Company, $23.95.

In 1856 William Perkin, an 18-year-old British chemist, tried to synthesize the antimalarial quinine from coal tar, a by-product of gas manufacture. Instead, his experiment yielded an inky dark residue. Intrigued, Perkin purified the substance, ultimately creating a light purple liquid. Taken with the color, Perkin, who was also an amateur painter, dipped a silk cloth into the liquid; the material turned a striking— and permanent— lilac. Perkin had stumbled upon the first artificial aniline-based dye. He dubbed the new compound mauveine, derived from mauve, the French word for the common mallow plant. Mauveine quickly became a success, thanks in part to trendsetting Empress Eugénie of France, whose fondness for the shade sparked a "mauve mania" in 1850s Europe. Mauveine, and a rainbow of other artificial dyes Perkin developed, were churned out by his own chemical works, and he rapidly became wealthy. His name lives on in the Perkin Medal, awarded annually in the United States to recognize achievement in applied chemistry.

Mauveine marked a new closeness between science and industry that has had a far-reaching impact. As Garfield chronicles, Perkin's success occurred at a time when England was lagging behind much of Europe in scientific pursuits and was in the midst of considerable distrust between industry and researchers. Although the dyes were developed in Britain, they were soon pirated by others. Germany, with a history of cooperation between science and industry and a healthy tradition of research, was poised to exploit the field. Germany's growing dominance and the stress of patent disputes led Perkin to sell his chemical works in 1873. By the outbreak of World War I, 85 percent of artificial dyes used in Britain were imported, and authorities had to scramble to find supplies to dye soldiers' uniforms. — Margaret Foley

Tales from the Underground: A Natural History of Subterranean Life

David WolfePerseus Publishing, $26.

Wolfe, an ecologist, delivers a pointed challenge to his readers, most of whom he assumes are "surface chauvinists." Step outside the door and scoop up a handful of dirt. In just that small patch of soil, he says, are close to a billion organisms— everything from microscopic roundworms to gossamerlike fungal threads. Then consider the globe, and ponder what scientists are now saying: The total mass of living matter above Earth's surface is dwarfed by what exists below.

Researchers have recently discovered millions of new species of living organisms— not only in the topsoil but also in deep regions of Earth that were once considered sterile. Microbial organisms flourish two miles down at temperatures near the boiling point of water. Biologists suspect that these subterranean habitats may be where life on Earth first began.

Besides furnishing plants with vital nutrients like nitrogen and potassium, organisms found underground are being used to fight plant diseases and to create new antibiotics. Indeed, Wolfe argues that the potential utility of the 10,000 species contained in a pinch of earth should be an incentive to protect dirt, a task that is taking on increasing urgency. In the United States, soil is eroded 10 times faster than it is formed. — Eric Powell

We also like...

The Dragon Seekers: How an Extraordinary Circle of Fossilists Discovered the Dinosaurs and Paved the Way for Darwin

Christopher McGowanPerseus Publishing, $26.

Terrible Lizard: The First Dinosaur Hunters and the Birth of a New Science

Deborah CadburyHenry Holt and Company, $27.50.

Paleontologist McGowan and science writer Cadbury recapture the giddy early days of British paleontology, when "geological gentlemen" in the new field of "undergroundology" uncovered the remains of an extinct marine reptile, Ichthyosaurus, and the first dinosaur, Megalosaurus.

In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It Made

Norman CantorThe Free Press, $25.

In a chilling narrative, medieval historian Cantor charts the surprising and significant changes wrought by the devastation of the black death, including a revolution in the arts and the creation of the first class of independent farmers.

The Executive Brain: Frontal Lobes and the Civilized Mind

Elkhonon GoldbergOxford University Press, $29.95.

Half a Brain Is Enough: The Story of Nico

Antonio M. Battro Cambridge University Press, $17.95.

Neuropsychologist Goldberg mixes memoir with neuroscience in his exploration of the brain's frontal lobes, which control judgment and social behavior. Cognitive psychologist Battro relates the extraordinary story of Nico, an epileptic boy whose neurons rewired themselves to compensate for the surgical removal of his brain's right hemisphere. — Eric Powell

Tops, Bots, and Yo-yos:At www.tetratops.com, you can find pictures, facts, and video, as well as simulations of Przybilla's tops spinning in zero gravity.

"The Unfolding World of Chuck Hoberman," by Tom Waters, Discover, March 1992, pp. 70-78. http://208.245.156.153/archive/output.cfm?ID=10

A history of yo-yos is available on Duncan Toys' Web site: www.yo-yo.com.

See video of Brown's yo-yo tricks at http://www.yoyoguy.com/yoyo/duncan/Steve_long_trick.mov and at http://www.yoyoninjaboy.com/dojo/masters.html

Przybilla's patent #5,996,998 is available at the US Patent and Trademark Office's website, www.uspto.gov.

Seed Savers Exchange: For a 68-page color seed catalog (and membership information), call 319-382-5990; www.seedsavers.org has additional information about the organization and Heritage Farm.