One by one, the brown-eared bats squeeze through a six-inch hole and emerge into deepening twilight; an instant later, they've fluttered off to feed. At Kartchner Caverns, flocks of bats have repeated this ritual each summer evening for 40,000 years. But these days, with the advent of tourism, the bats are not the only creatures shuttling in and out of this labyrinthine world of darkness. Since Kartchner was opened to the public two years ago, tours have been selling out weeks in advance. So far the bats still appear to be thriving. But the cave itself may be dying.

Kartchner Caverns

Two cave enthusiasts discovered Kartchner Caverns in 1974 but kept their find a secret for 14 years. Now, 500 tourists daily go underground to visit the stunning flowstone formations. Photograph courtesy of Kartchner Caverns State Park

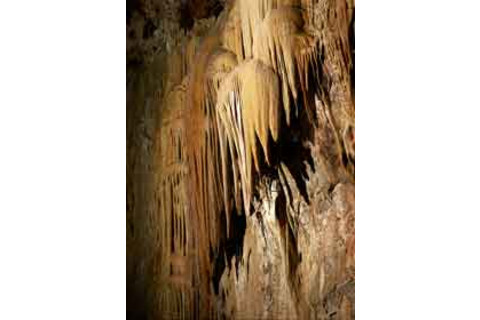

Located just 30 miles north of the Mexican border in southern Arizona's austere Whetstone Mountains, Kartchner is a pristine example of a living cave, with formations that are still moist and growing. The brilliant orange, red, and gold stalactites and stalagmites in the caverns have been formed and fed during the past 200,000 years by rainwater that combines with carbon dioxide from the air and carbon from the soil, trickles through limestone, and finally seeps through the earth to deposit mineral-laden droplets. The state of Arizona recently spent 12 years and $30 million to turn this subterranean fairyland of spires, turrets, and shields into what officials have dubbed the Environmental Cave, taking pains to protect it from the potential damage caused by tourism. Kartchner's formations depend on moisture, so humidity must be maintained at 99 percent or the fantastic structures will stop growing. A temperature variant of just half a degree can dry out the cave within weeks. But there's a scalding desert above and 500 tourists come through each day, so visitors must enter through two steel doors designed to keep the hot air from seeping in. Misters spray the cave floor to keep it damp.

Visitors are treated to an impressive, if garish, display: At the end of the tour, in front of the grandest formation of all, the cave suddenly goes dark, New Age music swells, and dozens of pulsating lasers swirl about the towering Kubla Khan, a 58-foot-high column of sandstone. And that is part of the problem. The high intensity of the lights, say cave specialists, can cause algae to grow on the formations and dull them. The humidifying misters may be causing additional damage by disturbing airflow patterns, air temperature, and mineral deposits, and by disrupting the delicate ecosystem supporting the cave's various life-forms. Despite protests from scientists, the misters now run around the clock--not 12 hours a day, as originally planned--to compensate for the unexpected impact of tourists. Yet, the cave is still drying out. One year after Kartchner opened, it was less humid and one degree warmer in areas where the public visits. (Despite several requests, officials failed to provide new data.)

Flowstone lumps are one of 32 types of calcite formations--including stalactites, stalagmites, and soda straws--at Kartchner. Photograph courtesy of Kartchner Caverns State Park

Park officials have suggested that the cave is dry because of a recent drought and note that hard rains have since fallen and added moisture. Nevertheless, they've hired a paleontologist to assess the impact of tourism on the cave and to devise new ways to avert further damage. Ronal Kerbo, the National Park Service's leading expert on cave preservation, remains optimistic but warns, "Kartchner will never be a pristine environment again. This is what happens when you open a cave to the public and say, 'Come on in.'"

Nov 2001 Exhibits

The World's Last Great Places Twelve photographers reassess our relationship to nature

Is it possible to stand on the valley floor at Yosemite and gaze upon Half Dome without feeling the ghost of Ansel Adams? Or how about glimpsing a full moon poised above the High Sierra? That moment also belongs to Adams, a photographer who frame by frame captured an American wilderness that was gorgeous, pristine, and above all unmolested by man. The pleasure we take in an Ansel Adams photograph feels slightly illicit, because he brought us images of places whose very appeal was predicated on our willingness to leave them alone.

Richard Misrach captures the watery oasis of Carson Sink in northwest Nevada's desert.Photograph courtesy of Richard Misrach/The Nature Conservancy

"In Response to Place," a photo exhibit on display through December 31 at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., and in cities nationwide thereafter, offers a surprising reappraisal of what constitutes natural splendor. The show was conceived to mark the fiftieth birthday of the Nature Conservancy, which controls more than 12 million acres of wilderness in the United States and more than 96 million acres worldwide. Curator Andy Grundberg asked 12 photographers to make studies of sites designated by the Conservancy as "Last Great Places." Earlier attempts to modernize the beloved landscape tradition have dwelled on man's desecration of nature. "In Response to Place" instead makes the case that humanity is just another one of nature's elements--no more and no less. The thesis brings us down to size and invites us into the frame. Indeed, four of the photographers--Sally Mann, Annie Leibovitz, Fazal Sheikh, and Mary Ellen Mark--have built their formidable careers on portraiture.

Mark visited the Virginia Coastal Reserve and the Pribilof Islands in Alaska, two isolated coastal wildernesses that are homes to a stunning array of marine and bird life as well as to gritty, unpampered human populations. Her 13 photos reveal landscape only incidentally--and sometimes not at all. Mark is content to let nature reflect in the faces and gestures of her subjects, suggesting that human nature can be as chafed and in need of remediation as any stressed ecosystem.

Photographer Terry Evans returned this specimen of th herb Verbascum thapsus to its original place on the 39,000-acre Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in the Osage Hills of Oklahoma.

Photograph courtesy of Terry Evans/The Nature Conservancy

"Camera images mediate between the visible, describable world and the intentions of the human observer," says curator Grundberg in his introductory essay to the exhibition catalogue (Bulfinch Press). Terry Evans's images of botanical specimens set and labeled on paper and placed on the ground in their natural habitat, Oklahoma's Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, wryly demonstrate Grundberg's point. Humans may participate in nature's pageantry but are distinguished by self-consciousness. Evans's photos reveal the analytical mind at work--hers and, by implication, ours. In a thicket of sneezeweed lies a specimen of the plant that has been plucked and identified as Prunus serotina: nature, and nature objectified. — Kim Larsen

Nov 2001 Science Toys

Moving MadnessFor those bored--yawn--by the conventional puzzle

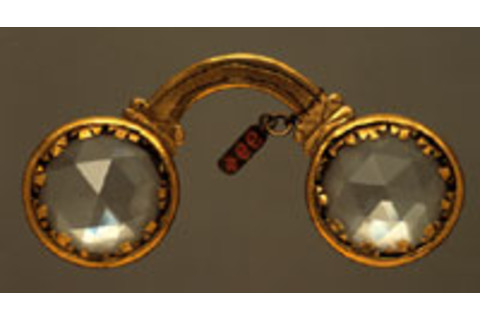

Enjoy the challenge of a jigsaw puzzle? Then try tackling one that doesn't stay put. The images on Dynamix Moving Jigsaw Puzzle pieces shift depending on the angle from which you view them, making it quite difficult to tell which piece you're holding, let alone if it's the one you're looking for. The puzzles, from Blue Opal and their U.S. distributor, Binary Arts create the illusion of movement using a process called lenticular imaging. To produce one of the puzzles, a series of time-lapse images are cut into narrow vertical strips. A strip of image one is placed next to the corresponding strip of image two, followed by strips from image three, image four, image five and so on; then the pattern is repeated, beginning with the next strip of each image. When all of these strips are in place, they are laminated with a lenticular sheet--a clear plastic film embossed with tiny elongated lenses, each of which spans the entire width of the puzzle. As each puzzle piece, or any section of the puzzle, is tilted back and forth, the change in viewing angle brings a different strip from a different image into focus behind each lens.

The lenticular puzzle was invented by Dugald Keith, who holds a degree in physics. Assembling this 250-piece jigsaw may require five painstaking hours of dizzying labor.

The swimming fish in "Underwater Life" ($24) appear to be moving in liquid space and prove to be almost as elusive as their real-life counterparts. Be prepared to spend hours sorting through the puzzle's 250 pieces. If you prefer not to spend your time on fish, try the moving cars of "Super Highway," or the Escher-like stairs of "Paradox," 250 pieces each. Then there's the whopping 500-piece "Floral Portrait" ($30), which shows several types of flowers growing from bud to full bloom. You might want to enlist friends to help with that one; just try not to bang heads as you and the puzzle pieces move in and out of focus. — Fenella Saunders

Nov 2001 Books

Fly: The Unsung Hero of Twentieth-Century Science Martin Brookes Ecco, $24.

The lowly fruit fly has been the star of biological research for nearly a century, at the nexus of genetics, embryology, evolution, and animal behavior. As early as 1909, fruit flies (in this case Drosophila melanogaster) gained notoriety when Columbia University researcher Thomas Hunt Morgan studied the genetics of eye-color change from red to white, providing important data to back up the research of 19th-century geneticist Gregor Mendel.

Before long, scientists had brought in a new player from the wild, D. pseudoobscura, to use as the insect equivalent of laboratory mice. It has been joined by a whole host of mutants (such as the long-living D. methuselah and the alcohol-sensitive D. cheapdate), all providing valuable insights into human ailments, including congenital learning disabilities, sleeping disorders, jet lag, alcohol, drug addiction, and even neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Huntington's.

What accounts for the fruit fly's extraordinary popularity among researchers? It's cheap to maintain, and it reproduces like crazy. Better yet, a fruit fly's entire life span is over in just a few weeks, which makes it possible to observe many generations of evolution and mutation quickly. Ironically, experiments with the short-lived insect may help lengthen human life spans. In his chapter "Helping the Aged," Brookes muses: "Today, laboratory flies are living longer lives and growing old more gracefully than ever before. . . . Who knows, the fly may yet provide an escape route from our own mortality." — Shannon Brady Marin

This Man's Pill: Reflections on the 50th Birthday of the Pill

Carl Djerassi Oxford University Press, $25.

Carl Djerassi is fond of referring to himself as the "mother of the pill." In 1951, Djerassi and other organic chemists at Syntex, the Mexico-based pharmaceutical company, synthesized a form of progesterone called norethindrone, later the active ingredient of the contraceptive pill.

Now also a novelist and playwright, Djerassi devotes several essays in this autobiographical collection to the ideas that lie behind a literary genre he calls "science-in-fiction." But at the heart of the book are his ruminations about the social impact of the pill, both present and past. He assesses the prospects for a male pill (slim, since pharmaceutical companies see the profit margins as too small and the potential for lawsuits too big) and explains why Japanese women had to wait until 1999--after the sale of Viagra was given swift approval-- to be granted legal access to the pill (it was said to promote promiscuity). Djerassi also addresses the 10-year-long struggle in the United States to gain approval of the abortion pill RU-486 (mifepristone), a chemical cousin of the oral contraceptive. American antiabortionists branded it a "death pill" and vowed to attack any company that manufactured it."The outrage of the antiabortionists was understandable," Djerassi writes, "because RU-486 promises to decentralize the provision of abortion to a woman's bedroom, which can neither be bombed nor picketed." — Josie Glausiusz

We also like...

Hurricane Watch: Forecasting the Deadliest Storms on Earth

Bob Sheets and Jack Williams Vintage Books (Random House), $15.

A chronicle of the history and science of hurricane forecasting, with harrowing accounts of some of Earth's most devastating storms.

Fire in the Turtle House: The Green Sea Turtle and the Fate of the Ocean

Osha Gray Davidson Public Affairs, $26.

Science journalist Davidson details the beauty and mystery of the endangered sea turtle and reports why researchers' efforts to save this marine reptile from extinction, after more than 100 million years on the planet, may be the species' only hope for survival.

Decoding Egyptian Hieroglyphs: How to Read the Secret Language of the Pharaohs

Bridget McDermott Chronicle Books, $18.95.

Return to the time of the Pharaohs. This richly illustrated book by Egyptologist McDermott explores various facets of Egyptian culture through the hieroglyphs that were used in daily life and accompanied the rituals of death. Also included are myriad translations of key symbols, phrases, and texts.

The Riddle of the Compass: The Invention That Changed the World

Amir D. Aczel Harcourt, $23.

Aczel, author of the best-selling Fermat's Last Theorem and the son of a ship captain, delves into the discovery and development of the magnetic compass, a simple object that revolutionized navigation on the high seas.

The Language of Cells: Life as Seen Under the Microscope

Spencer Nadler Random House, $24.95.

A surgical pathologist for more than 25 years, Nadler recounts his experiences working with patients he came to view as much more than amalgams of individual cells. — Maia Weinstock