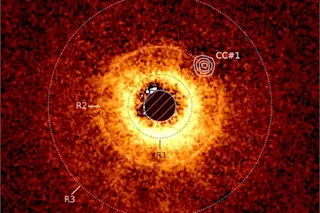

Since the discovery in 1995 of a planet at 51 Pegasi, astronomers have been furiously searching for planets around hundreds of other stars-- and by the end of 1996 they had found more of them, about a dozen, than circle our own sun. Some of the new planets, like 51 Peg B, are perilously close to their own suns; some are several times the size of Jupiter but swing in elongated orbits; and some, like the planet found around the dim star Lalande 21185 by George Gatewood of the University of Pittsburgh, look a lot like objects in our own backyard. Gatewood’s planet is about the size of Jupiter and makes a complete orbit every 5.8 years--about half as long as it takes Jupiter to orbit the sun. Since Lalande 21185 is only eight light-years from Earth, it may be possible to see its planet with the Hubble telescope. That would be satisfying: so far the new planets are known only from the way their gravity perturbs the motion of the parent stars.

Now that discovering planets is no longer front-page news, some of the emphasis has shifted to explaining why so many of them are so eccentric. In the view of some theorists, several of the putative planets may actually be brown dwarfs: stars that formed with too little mass to sustain nuclear fusion. Unlike planets, which form in a disk around the parent star and have roughly circular orbits, brown dwarfs coalesce from their own clouds of gas and dust and would tend to adopt highly elliptical orbits around their stellar partners. If the plane of the orbit happened to be nearly perpendicular to our line of sight, the theorists argue, the dwarf’s tug on its partner might be hard to detect--making an object that was actually between 20 and 80 times as massive as Jupiter seem small enough to be a planet.

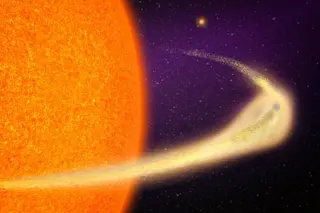

But this scenario has trouble accounting for the planet around 16 Cygni B, whose existence was announced in October by Bill Cochran of the University of Texas. Orbiting one of a pair of sun-size stars some 70 light-years from Earth, it is certainly eccentric: if it were in our solar system, it would careen from outside Mars in past Venus and back every 2.2 Earth years. Yet Cochran puts its mass at just one-and-a-half Jupiters, making it a very unlikely brown-dwarf-in-disguise. Says Doug Lin, an astrophysicist at the University of California at Santa Cruz, How many times can one use the orbital inclination argument? You’re allowed to use the tooth fairy once or twice but not every time.

Lin suggests another explanation for eccentric planets: they may be remnants of one or more gas giants that crashed together. The key, Lin says, is to form several Jupiters in the outer part of a solar system; their gravitational interaction would eventually make their orbits cross, leading to spectacular collisions. The resulting planet would have several times the mass of Jupiter and an orbit as elongated as some comets.

Lin’s model suggests that the amount of stuff you start off with in your protoplanetary disk determines the kind of solar system you get. A heavy disk leads to lots of big planets that eventually crash into one another; a medium-size disk creates fewer big planets but tends to drag them close to the star, like 51 Peg B; a puny disk produces a couple of giant planets that stay put, as in our own solar system. But even our solar system, says Lin, may have had its own 51 Peg B that kept going, plunging into the sun and taking with it whatever lay in its path. If so, Mars, Earth, Venus, and Mercury may be a second set of inner planets--the first having been swallowed by the crashing giant.

To find out whether Lin is right will require finding not just more planets but more around the same star. So while other hunters scan new stars, Gatewood is focusing on the ones that already have planets, looking for the slow sway that would signal other companions farther out. He has lately found a second planet around Lalande 21185, at Saturn’s distance from the sun. We have to look for such a long time at every star that we can’t look at very many, Gatewood says. But somebody has to follow up and do the housework.