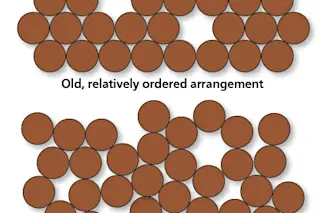

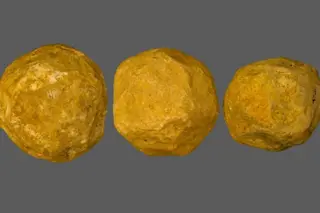

Toss a bunch of pennies flat on a table, and then push them together until they’re tightly packed and can’t move any closer. They’ll form nearly perfect hexagons, with only an occasional spot that’s more disordered. Researchers had long thought that these “relatively ordered” arrangements were the most random ones you could get in the circumstances.

But early this year, Princeton materials scientists Steven Atkinson, Frank Stillinger and Salvatore Torquato found significantly less dense configurations by pushing the pennies together as if they were on a shrinkable pad of rubber rather than a rigid table, until reaching the “no closer” point. The resulting arrangements contain few hexagons; the pennies in these new configurations touched an average of only four others.

And the results scale up: The researchers found a new mathematical method to arrange matter — not just pennies, but all particles. These new, less-dense configurations point the way toward ...