Last year, astronomers turned to the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy to watch it tear apart a dusty gas cloud called G2. It was an event widely anticipated, including in Discover (“To the Edge and Back,” September 2014, “When a Slumbering Monster Awakens,” April 2014 and “Our Black Hole Lights Up,” January/February 2014).

The discovery of G2, which was estimated to have the mass of three Earths, was announced in January 2012 by Stefan Gillessen of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. Gravity from the black hole, called Sagittarius A*, already had begun stretching G2, Gillessen’s team said.

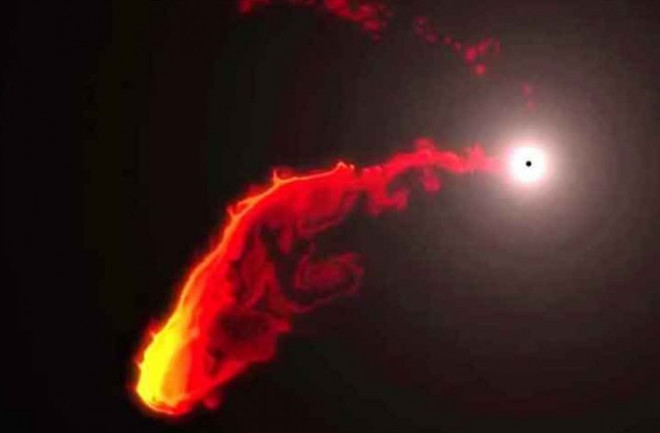

The gas cloud was expected to make its closest approach in early 2014, plowing through the hot, magnetic plasma that surrounds the black hole. G2 would stretch like soft taffy and glow in X-rays, and some of the gas would spiral down the black hole, spewing radiation as it did so. This was a chance to watch Sagittarius A* dine — a rare show.

But there was no such spectacle.

UCLA’s Andrea Ghez and colleagues had long expected such a flop. Since August 2013, they have argued that G2 isn’t just a cloud, but instead a star shrouded in gas and dust. That would make G2 anywhere from 100,000 up to 1 million times more massive than what Gillessen’s team thought, and thus Sagittarius A* would have a harder time pulling material off the object. If that’s the case, it’s no wonder the galactic center didn’t light up.

But is G2 really a star hiding below gas and dust? Gunther Witzel, a member of the Ghez team, says they don’t know conclusively. The way to find out is to watch how G2’s orbit evolves on its trip through the galactic center. A starlike G2, Witzel says, would barrel through the hot plasma near the black hole, staying on its extremely elliptical 300-year orbit. But a cloudlike G2 would feel a drag, like a feather moving through air on Earth, says Ann-Marie Madigan of the University of California, Berkeley, who’s not affiliated with either team. That drag would tilt and shrink the gas cloud’s orbit while also possibly tearing apart the cloud.

Madigan expects at least three to five more years of observations before scientists can say with certainty what G2’s orbit does — and what exactly G2 is.