It kept going through the pandemic. It kept going through an overwhelming election season. It kept going in the face of bad news about wildfires and good news about lunar exploration. Through it all, tabloid newspapers and clickbait websites kept hyping stories about "killer asteroids" headed our way — and people kept reading, clicking, and worrying.

No doubt, a lot of people enjoy those kinds of stories because, deep down, they don't believe the catastrophe is going to happen; it's fun to imagine precisely because it seems fantastical, like watching New York and L.A. get torn apart in a Hollywood disaster movie. And to be clear, asteroid impacts are real thing, as frighteningly demonstrated by the 20-meter-wide rock that exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013, injuring more than 1,500 people. There is good reason to study asteroids, understand the risks, and develop ways to deflect a threatening object if need be, as I discussed in my previous post.

But judging from the questions I see on Twitter and posted on Quora, there are a lot of people who sincerely overestimate the risk of a big asteroid crashing into Earth, and who suffer a lot of misplaced anxiety as a result. There are enough genuine, immediate risks to worry about in the world right now, including risks that you personally can influence. (Wear a mask, keep appropriate distance, and avoid large gatherings!) If you want to help defend the planet, you can join an amateur astronomy group or tell your representatives to support asteroid research and planetary defense. You can also enjoy the remarkable discoveries from the world of asteroid science, and share them with people who know too much of the fear and not enough of the joy in this field.

I'm trying to do my part to address the concerns. So here I've compiled responses to a few common types of questions I've received about the dangers from asteroids.

Type 1: Could there be a giant, unknown asteroid bearing down on Earth? I frequently see what-if questions on Quora long these lines, typically involving a Texas-size (or Europe-size, or Moon-size) asteroid that is less than a year from hitting when we discover it. This is similar to the scenario in some of the more over-the-top Armageddon-style flicks.

Nothing to worry about here. Nothing at all. A Texas-size asteroid that will hit the Earth in one year? Impossible. A Europe-size asteroid? Completely impossible.

There is no object that big in the asteroid belt. The largest asteroid, Ceres, is about the size of Spain and France put together. That's a bit bigger than Texas, and maybe large enough to call it the “size of Europe,” but Ceres is in a stable orbit, far away from us. It is completely ruled out as a threat.

If you want to go for an all-out disaster scenario, you're better off looking to the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune. The largest objects in the Kuiper Belt — Pluto and Eris — truly are Europe-size but, like Ceres, they are in stable locations and are not heading our way even on a geologic timescale. The big objects in the Kuiper Belt are so few in number and so widely distributed that the change of any one of them being perturbed into an Earth-intersecting orbit is essentially zero.

There are many smaller, more easily disturbed objects in the Kuiper Belt; this region is the source of some of the comets that we see in the inner solar system. Those bodies are much smaller, however, typically no more than a few kilometers wide, and even so they would be easy to see well in advance. The ones that migrate inward are also rare enough that major comet impacts on Earth happen tens of millions of years apart, on average.

Nature is kind to us in an important way: The bigger the potential impactor, the easier it is to spot and the harder it is to perturb. As a result, we would have a lot of advance warning if there was even a minuscule chance that a large object was on a collision course.

If we're talking about a continent-size Kuiper Belt object, astronomers would have already spotted it unless it was at least 50 to 100 AU (Sun-Earth distances) from the Sun. From that distance, an object would take about 200 years to reach the inner solar system. We’d have a couple centuries of advance warning, not one year. And such an object would travel through the inner solar system with little consequence unless it passed very close to Earth—an extremely unlikely event on top of another extremely unlikely event.

If you want to game out every possible disaster scenario, you can consider one more: an interstellar object entering our solar system at high velocity. The two known interstellar comets — ‘Oumuamua and Borisov — entered our solar system at a speed of about 5 AU per year. If we spotted an interstellar Pluto headed our way, and we spotted it at a distance of 50AU, we might then have only a decade or so of warning. For 'Oumuamua and Borisov, we had far less warning, because they are both tiny. Again: The bigger the object, the more advance notice you get.

An interstellar comet impact is the disaster scenario du jour; it is the premise of the upcoming movie Greenland, which deals with the risk in an unexpectedly plausible way. But note that we are talking about much smaller objects than the one in the original question; 'Oumuamua was only about 300 meters long! Even these little things are rare enough that astronomers had to search for years before finding one. We have no idea if continent-size interstellar Plutos even exist. At any rate, they've left no sign of their existence. If anything in the solar system had been hit by such an object in the past 4 billion years, for instance, we'd see the evidence.

Bottom line: The last time a continent-size object struck the Earth was 4.5 billion years ago, when it led to the formation of the Moon. The likelihood that it would happen in your lifetime is extremely close to zero. The likelihood that it would happen with just one year of advance warning is exactly zero. It simply cannot happen.

Type 2: Could another asteroid like the one that killed the dinosaurs hit us with almost no advance warning? In this case, the size of the asteroid is more plausible; after all, Earth really was struck by a 10-kilometer asteroid 66 million years ago. But for the same basic reasons that I outlined above, there is no way that such a large object could be on a near-term collision course with Earth without us noticing it. We have already observed every asteroid that large and plotted its orbit. There is nothing that large out there heading toward us.

The question is as far-out as asking, “Could a supervolcano suddenly blow up under New York City?” or “Could you wake up tomorrow and find out there's a 1,000-kilometer-wide hurricane over Denver?” It might make for a fun what-if, but it's not a real-world possibility.

There are only two kinds of disasters I can think of that could cause a global disaster with just a few days of advance warning:

An all-out nuclear war specifically designed to extinguish humanity, targeting the 10,000 largest cities around the world.

Divine intervention.

Seriously, that’s it. There are some exotic possibilities that could wipe out much of the planet in the blink of an eye (my favorite is a collapse of the vacuum-energy density), but we’d have no warning that it was about to happen. There are other high-speed disasters we could see coming, like a solar superflare, but that would not be world-ending. But there is no known natural disaster that could destroy the world in such a fast yet foreseeable way.

Bottom line: If you see a story suggesting an imminent asteroid disaster, it is bogus. Any asteroid big enough to cause global damage is something we'd know about far in advance. Any asteroid small enough that we don't know about it could not cause global damage. There are bona fide asteroid risks, as demonstrated by the Chelyabinsk incident. That's why it's important to complete our survey of near-Earth asteroids, and to develop better advance warning systems for incoming objects that too small to detect far from Earth. But these are entirely different categories of risk.

Type 3: I heard that asteroid Apophis is going to hit the Earth on April 13, 2029. Is this true? This is by far the most common type of question I hear, and the most common type of irresponsible journalism I see online. (The particular asteroid in the headline often changes, but the idea is always the same.) These stories contain a nugget of truth, because they are about genuine near-Earth asteroids that do make close approaches to our planet. But they distort that nugget of truth into a pile of...well, something not very nice-smelling.

Often the "close" encounters hyped in clickbait stories will pass millions of kilometers from the Earth, much farther than the Moon. Often the object in question is also extremely small, like the so-called "election asteroid" that passed Earth shortly before election day this year. Even if it had hit, it would have been completely harmless. Sometimes the stories build more closely on reality, though, and these are the ones that require the most decoding.

Apophis truly will make a close encounter in 2029, passing about 32,000 kilometers from Earth. That distance is well established. The asteroid will miss us. There is zero chance of a collision. On the other hand, after the encounter, its new orbit could send it on a collision course in 2068. The chance is tiny, but not zero. That's why astronomers emphasize the importance of studying asteroids and learning how to deflect them if necessary.

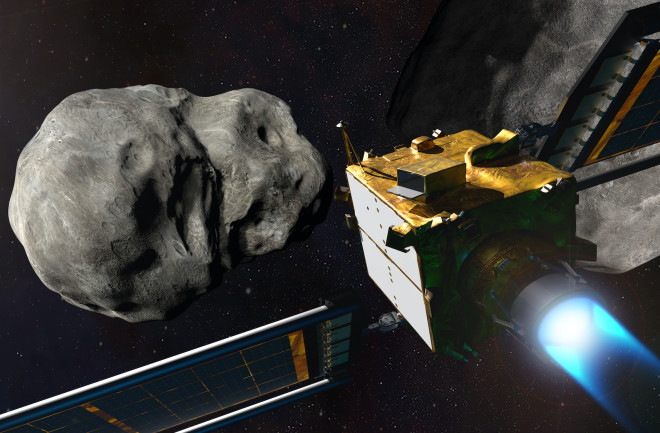

Apophis is about 300 meters wide, large enough to be quite dangerous. But keep in mind that even in 2068 the odds of collision are extremely low. Keep in mind, too, that we will have decades to study its orbit and to determine if the risk is significant enough that we should do something about it. And if it is, we can act! There are numerous ideas about how to deflect an asteroid. The DART mission, launching next summer, will test the effects of a controlled impact on an asteroid, one possible deflection technique.

The same is true for all of the other near-Earth asteroids. Astronomers keep close tabs on impact risks from known asteroids. If you want to check out the raw numbers, you can see for yourself at the JPL Small-Body Database Browser and clicking on “close approach data.” You don't need to take the word of some rando on social media or a website that's also pushing stories about celebrity feuds and ghost sightings.

Bottom line: Whatever asteroid you've heard is going to hit the Earth, it's not. If there were any asteroid or comet out there — any one at all — that had a significant chance of impact, everyone in the scientific community would be talking about it. There would be scientific conferences about it. Top researchers would be posting about it on Twitter and Facebook. There would be nonstop coverage of it on cable news. You would not learn about it from a wheezing British tabloid.

If you don’t hear scientists talking nonstop about a likely future impact, there is only one explanation: It’s not going to happen. The story is a hoax or it is an act of scaremongering, spread by someone who is either gullible or who is actively trying to deceive you. Ignore it and move on. There are more important things to worry about in life. There are more important things to celebrate, too.

For more science news and reality checks, follow me on Twitter: @coreyspowell