Let's hope it never comes to this. (Credit: muratart/Shutterstock) Asteroid impacts have the distinction of being one of the few sci-fi concepts that will definitely happen at some point. But despite the clear and present (although potentially far off) danger of getting smacked by an asteroid, we've devoted few resources to averting such a catastrophe. As Discoverreported in 2013, NASA's budget for such operations makes up only a fraction of their budget, although it has risen in recent years, and it's unclear how that might change under the Trump Administration. NASA in 2015 ended an agreement that provided non-financial support to the Sentinel mission — designed specifically to pinpoint incoming asteroids — and similar asteroid defense projects are largely dependent on private donations. In a new report, a coalition of federal agencies is making the case to increase support for detection and deflection efforts, laying out a multifaceted, long-term blueprint to defend Earth from rocky invaders. The interagency working group comprises members of NASA, FEMA, the Department of Defense and the Department of Homeland Security, among others. The coalition convened in January 2016, and its first report was released on the heels of an asteroid impact response simulation conducted by NASA and FEMA in California.

The Big One

A rock 40 or 50 meters across could take out a city, and something substantially larger — a kilometer or so across — could lay waste to an entire continent. The 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor, just 20 meters across, exploded over Siberia, shattering windows and injuring hundreds as a result. The 1908 Tunguska event, also in Siberia, leveled over 700 square miles of forest and exploded with a force equal to approximately five to 10 megatons of TNT. In both instances, there wasn't an impact. While we don't know what a potential impact might look like, simulations of a large rock hitting both the land and the water hint at the frightening aftermath. Still, there's a roughly 1 in 100,000 chance that an asteroid will hit Earth with country-leveling force. But Chelyabinsk-size objects, big enough to cause damage, yet small enough to potentially escape detection, are cause for worry. If history is any indicator, we're due for one of them once or twice a century, and a Tunguska-size event every few centuries. "The big gaping hole, as pointed out in this report, are asteroids between the size of something only large enough to destroy a city and all the way up to 140 meters," says Ed Lu, a former astronaut and CEO of B612, a advocacy group focused on asteroid impacts.

Eyes On the Sky

Lu points to a space telescope called NEOCAM currently being developed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, to scan the areas of the solar system nearest to Earth. The project was passed over for funding from NASA's Discovery Program, which would have provided extra support for the mission. The telescope is meant to locate and track smaller asteroids that fall into the 20-140 meter range, and, when it's completed, will be a complement to the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope currently under construction in Chile, Lu said. LSST is optimized to find smaller objects in our solar system, and is set to begin operations in 2021. The asteroid defense working group estimates that there are around 10 million near-earth objects 20 meters or smaller, and some 300,000 larger than 40 meters that we don't know about yet. NASA currently lists only 15,413 near-Earth objects, of which 1,763 are classified as Potentially Hazardous Asteroids. Says NASA in an emailed statement: "In fiscal year 2010, the NEO Observations Program funded 21 projects to find, track, and characterize near-Earth asteroids. In fiscal year 2016, the program funded 34 individual projects to find, track, and characterize near-Earth asteroids plus nine studies of impact mitigation and deflection strategies and techniques. By October 2016, the number of discovered near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) topped 15,000, with an average of 36 new discoveries added each week. This milestone marked a 50 percent increase in the number of known NEAs since 2013, when discoveries reached 10,000 in August of that year. The discovery rate (number found per year) has increased 83% since 2013."

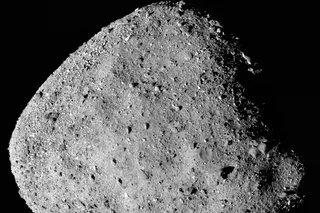

Eros, the second largest near-Earth asteroid at around 20 miles long and 7 miles wide. (Credit: NASA/JPL/JHUAPL)

How To Prevent the Apocalypse

The working group crafted a seven-part plan that addresses dangerous asteroids and the potential aftermath of an impact. The full proposal is set to be released at a later, unspecified date. Their first recommendation: Improve detection and tracking technologies. A space-based observatory dedicated to scanning the solar system for incoming asteroids would be optimal. Theoretically, it would give humanity enough time to hatch a defense plan. The group also called for improved models of asteroid behavior and composition to understand how any objects we find might respond to potential interventions. Emergency plans for the days leading up to, and following, a collision are also necessary, according to the working group. This entails building an international alert system and a means of coordination between national and international agencies. That means establishing protocols for communication and data sharing between international agencies. The report heavily stresses the primacy of international cooperation in the event of an asteroid impact — such an occurrence would surely require even rival nations to work together for the greater good.

A fireball streaks over the northeastern U.S. in May 2016. Finally, scientists need to study various ways to deflect an incoming asteroid from its path and save the planet, according to the report. This could take many forms: ramming a spacecraft into the asteroid, breaking it up with nuclear bombs, detonating explosives nearby to partially vaporize it and let the gases push it off course, or even painting parts of it black or white to allow the sun's light to push it in a different direction. Getting some practice is also part of the plan: The working group recommended conducting missions to asteroids to test technologies that would enable asteroid herding. This includes a nimble propulsion system, onboard artificial intelligence and monitoring systems for up-to-date assessments of the asteroid. We've already gotten a head-start. In addition to several asteroid rendezvous over the past two decades or so, the OSIRIS-REx mission, launched in September 2016, will make contact with with the asteroid Bennu in August 2018. The goal is to collect samples from Bennu and return them to Earth, a mission that will also test some of the protocols necessary for an asteroid-deflection mission, should it ever become necessary.

Detection Is the key

But before we get into the deflection business, we need a target. This is why Lu and others are pushing for better detection capabilities now. It could take more than a decade to fully design and equip a mission to coax an asteroid off its path toward Earth, so early warning will be key. Lu says that projects of this sort need to be viewed as more than just scientific missions, which has often doomed them to funding shortfalls. "It should not be judged in a pure science competition against other scientific missions with the criteria being how much novel new science you are doing," he says. "This is really something that is not just science, but it's really about protecting life." The money involved would barely make a dent in NASA's budget, to say nothing of larger agencies like the Department of Defense. "We’re talking half a percent of the budget of a small agency like NASA," Lu says. The problem may lie in the way that we as humans assess risk. We seem to have a tough time grappling with the consequences of events that we haven't personally experienced, and sometimes fail to take the necessary precautions. The 2011 Fukushima disaster and the failure of the levees after Hurricane Katrina are prime examples. "It's not as small as you think, it's just that it's longer than a generation," Lu says. "If it didn’t happen in your lifetime, you naturally discount it." [An earlier version of this story mistakenly stated that NEOCAM was passed over for funding. In fact, it is still being supported by NASA. Discover regrets the error.][This post has been updated with comments from NASA]