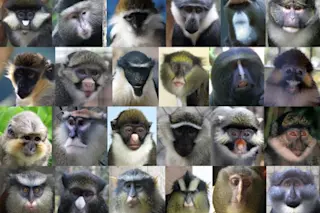

The cornucopia of guenon monkey faces. (Credit: William L. Allen and J.P. Highham/Nature Communications) The closely related guenon monkey species of Central and West Africa have a lot in common: they’re neighborly creatures that will travel, feed and even sleep together. But take an inventory of their faces, and you’ll see that no two species are alike. From Mohawks to colorful muttonchops, guenons use these distinguishing features to avoid mating with the wrong monkey. Using facial recognition technology, researchers from New York University and the University of Exeter have proven a decades’ old theory: guenons evolved facial features to stand out from the crowd. Their findings provide the best evidence to date for the role visual cues play in preventing breeding across species.

Revisiting an Old Hypothesis

Interbreeding is an evolutionary dead end for some animals, as offspring of these unions tend to be infertile. Since many species of guenons live in close proximity to each other and often intermingle, it made sense from an evolutionary standpoint that these creatures would differentiate themselves. Case in point: there are over 35 species of guenons, and each species proclaims its identity with uniquely colored eyebrow patches, ear tufts, nose spots and mouth patches. Thirty years ago, Oxford zoologist Jonathan Kingdon put these clues together and logically deduced that these were evolutionary differences designed to prevent hybridizing. However, his observations were based on the naked eye, and he failed to compile enough hard evidence to support his theory.

Technology to the Rescue

Three decades later, advanced facial recognition software has provided the evidence that Kingdon's theory lacked. Researchers photographed 22 species of guenons in zoos in the United States and United Kingdom, as well as a Nigerian wildlife sanctuary. They compiled roughly 1,400 photographs and loaded them into a computer. They used photo recognition software that analyzed facial patterns and noted key features. Then, researchers could compare the appearance of one species to another to see if their faces showed signs of hybridization. As expected, each species of guenon had facial characteristics that were visually distinct. Guenon species with overlapping territories — or those most at risk of interbreeding — had faces with even more pronounced differences, further supporting researchers’ hypothesis. They published their findings this week in the journal nature

Nature Communications.