The tomb of Tutankhamun was first found a century ago in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings in November 1922. It held thousands of fantastic artifacts, including clothing, chairs and chariots, as well as canopic containers and ceremonial statues. Yet, specialists say that in the years since the discovery, some of the tomb's artifacts have disappeared, potentially as a result of theft.

Now, new research presented at a conference in Luxor has identified some of these long-lost artifacts and located them in museums and auction sites across the U.S. and U.K. More than that, the research has also named the thief as none other than the archaeologist who was credited with their original discovery.

Lost And Found

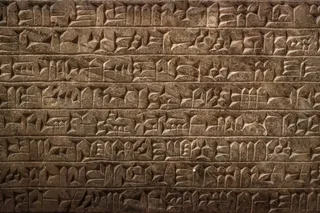

On Nov. 4, 1922, Howard Carter and his team found the steps to the tomb of the ancient pharaoh Tutankhamun. Within 20 days, they had already cleared the totality of the stairway of its dust and sand. When they opened the tomb, they uncovered thousands of “wonderful things,” as the British archaeologist described at the moment of the breakthrough. Thus began the daunting task of excavating and recording the over 5,000 objects held inside.

More about Tutankhamun:

Though the pharaoh and his tomb fascinate the world today, Tutankhamun was willfully forgotten in antiquity thanks to his successors, who erased him from official histories.

Of the over 5,000 artifacts found in his tomb, Tutankhamun’s funerary mask and iron meteorite dagger are two of the most famous and most mysterious.

Carter and his team spent the next 10 years cataloguing and photographing the contents of the tomb (both at the burial site and at a studio) before turning the artifacts over to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, as Egyptian laws expected at the time. Specifically, these laws stated that every artifact taken from the tomb belonged to the Egyptian state and could be taken beyond the Egyptian borders only with the state's explicit approval.

As such, when Carter passed the artifacts to the museum, he had claimed that any absent items had disappeared long ago, all the way back in antiquity. But accusations of theft eventually started to arise.

In recent years, evidence has mounted that Carter made off with several items from the tomb, but the identity and the location of these artifacts has remained mysterious. Now, the close inspection of the original images of the tomb and its treasures have allowed researchers to identify and locate several artifacts that the archaeologist may have taken for himself. Researchers presented the findings at the Centennial Tutankhamun Conference, which took place in November 2022.

To Catch a Thief

Aiming to discover the details of Carter’s supposed thievery, presenter Marc Gabolde studied the photographs of the tomb and its contents taken by Carter’s team. He compared the photographs to images of ancient artifacts from museums and auctions.

Eventually, Gabolde, who teaches Egyptology at the Paul-Valéry University of Montpellier, found several pieces of long-lost jewelry which were once taken from the tomb, as well as their current locations in collections around the world.

Some of these artifacts survive in a single piece, including a ceramic collar, which was displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York until it was sent back to Egypt in 2011. That said, many more of these artifacts are now scattered in several separate pieces.

For instance, beads from a collar which was originally positioned on the chest of Tutankhamun’s corpse have turned up at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, as well as in private auctions. Plus, beads from two other pieces of jewelry — a headdress and a necklace — have been found in the collections of the Saint Louis Art Museum and the British Museum.

“We have seen that not all of the jewelry found on Tutankhamun’s mummy went to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo,” Gabolde states in a pre-print of a paper about the research. “Carter kept some pieces for himself, and these are now on display in various museums.”

Read more: The 6 Most Iconic Artifacts From the Ancient World

Gabolde’s conclusions are consistent with other fresh work within the field, including the recent identification and publication of a letter sent to the supposed treasure-taker by a contemporary scholar in 1934. In the letter, Egyptologist Alan Gardiner claims that Carter had "undoubtedly stolen from the tomb,” taking an inscribed amulet that was part of a matching set from the site and passing it off to Gardiner as a gift.

Carter’s motivations for these thefts are still stuck in the shadows. Some scholars suspect that the archaeologist saw some of the tomb's artifacts as trivial and totally acceptable to pass around among friends and colleagues. Many more, including Gabolde, think that Carter illegally took the objects to continue the processes of preservation or analysis.

That said, whatever the motivations for these thefts, Gabolde's pre-print paper stresses that future investigations of museum and auction collections could lead to additional long-lost treasures.

“Recognition of relevant pieces is complicated,” Gabolde concludes in the paper, “but there is good reason to hope that more lost pieces from Tutankhamun’s tomb will ultimately resurface.”