SpaceX’s ambitious Starlink project could eventually launch more than 10,000 satellites into orbit and rewrite the future of the internet. But Elon Musk’s company has been taking heat from the astronomical community after an initial launch in late May released the first 60 satellites. The 500 pound (227 kg) satellites were clearly visible in Earth’s night sky, inspiring concern that they could increase light pollution, interfere with radio signals, and contribute to the growing issue of space debris.

This week, the American Astronomical Society, the International Astronomical Union, the British Royal Astronomical Society, and the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) all issued statements expressing concern about Starlink’s potential to damage astronomical research by leaving bright streaks through images.

“The Starlink affair has raised the attention of the astronomy community in a way that I’ve not seen during my couple of decades in it,” says John Barentine, director of public policy at the IDA, which lobbies against light pollution. “I hope that this moment is the wake-up call that is needed to prompt a new discussion in the international community about the nature of outer space, especially near the Earth, in a commercial context.”

Musk had repeatedly assured people on Twitter that his satellites wouldn’t be visible at night, so the light caught some people by surprise. However, the satellites’ initial brightness is intended to wane as they climb higher into their permanent orbits.

“The observability of the Starlink satellites is dramatically reduced as they raise orbit to greater distance and orient themselves with the phased array antennas toward Earth and their solar arrays behind the body of the satellite,” a spokesperson for SpaceX said in an email.

But Barentine and other astronomers aren’t so sure, especially given that this is only the beginning for Starlink. Plus, many other companies — including Amazon, Boeing, OneWeb, Telesat, LeoSat, and even Facebook — are planning other so-called “mega-constellations” for connecting the masses online.

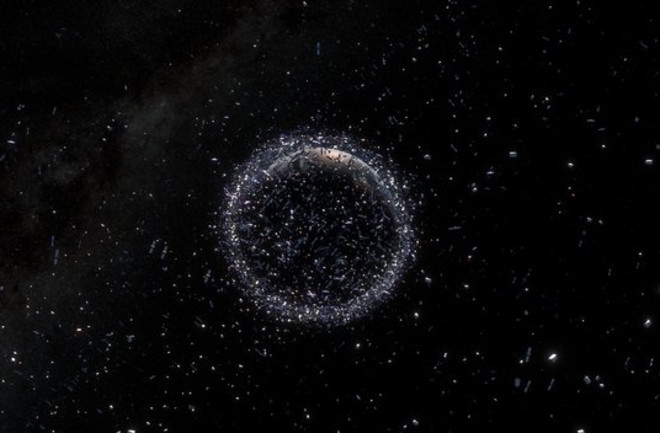

“There are billions of people around the world who lack access to broadband internet,” a spokesperson for Amazon’s Project Kuiper said in an email. “Our vision is to provide low-latency, high-speed broadband connectivity to many of these unserved and underserved communities around the world … Many of our satellite and mission design decisions are, and will continue to be, driven by our goals of ensuring space safety and taking into account concerns about light pollution.” But there are already 22,000 artificial objects currently in orbit. And as the microlaunch space race kicks into high gear, that number is destined to double. Communications satellites aren’t the only things headed up, either. One group even proposed launching orbiting billboards that would shine ads back down to Earth. And an artist recently launched the “Humanity Star” – a purely artistic light beacon.

“Space is already crowded, and roughly doubling the number of objects in low- and near-Earth orbit will only add to the visual pollution of the night sky,” Barentine says. “Being in a dark place and seeing one satellite fly over every few minutes is one thing. But seeing literally dozens of them at any given time for hours every night is another story entirely.”

Part of the reason this problem stands to get worse, according to astrophysicist Laura Forczyk, is “there is no regulatory body in the United States that directs companies as to the kind of light pollution or the brightness of satellites. This is a fairly new topic and as always the government regulations are behind technology.”

But Forczyk, owner of the space consulting firm Astralytical, also says that changing the night skies isn’t the same thing as losing the night sky — and it’s a little too early to know what the total impact is going to be. After all, the Starlink satellites still haven’t reached their final orbit. “We’re very reactive when it comes to these kinds of things,” she says, but emphasizes miscommunication from both sides.

Whether the problem stands to worsen or not, most experts see the growth of these mega-constellations as inevitable.

“I don’t think we’re going to be able to create political will to stop the satellites because there is so much commercial potential and politicians tend to respond to economics,” says Phil Metzger, a planetary scientist at the University of Central Florida and a former NASA physicist. However, he says future designs of satellites can ensure they’ll cause less interference with on-the-ground astronomy.

“We can change the surface of the spacecraft so it is more absorptive and less reflective or we can even make it more transparent,” Metzger says. “We do have the ability to make electrical conductors completely transparent so we don’t need metal. You could have glass with transparent conductors in the glass … I think we’ll probably be doing all of these things in the future.”