It’s been just over a century since British archeologist Howard Carter discovered the most prized collection of Egyptian antiquities ever found from within the tomb of King Tutankhamun. It was the only intact tomb ever discovered.

Grave robbers were fooled for nearly 3,000 years by the debris that covered King Tut's tomb, which was positioned beneath the tomb of Rameses VI.

Howard would find a host of priceless treasures within its chambers, including Tutankhamun’s gilded thrown, the Anubis Shrine, and the pharaoh’s famous death mask. Another curious and stunning piece found in the tomb was King Tut’s central pectoral scarab.

The Significance Of King Tut’s Pectoral Scarab

The elaborate golden pectoral is adorned with a bright yellow gemstone that makes up the scarab, a type of beetle. Made of Libyan Desert glass, it’s extremely rare for a piece of this size to be found. The glass was formed when a meteorite exploded into the sand in the eastern Sahara and made this stunning piece of glass later carved into a scarab and added to adorn this ceremonial pectoral, says Salima Ikram, an Egyptologist at The American University in Cairo.

“It’s remarkable because it shows us that the ancient Egyptians were making these explorations deep into the desert into places where even today, four-wheel drive could rarely make it, and they were doing it with donkeys,” says Ikram.

It was a rarity and would have been treated like a precious gem. That’s part of why it’s such a central jewel on this piece. Pectorals like this one would have been used both for religious purposes and for decoration—their role was one of protection and divine power.

Read More: Long-Lost Artifacts From King Tut's Tomb Are Finally Found

Why Were Scarabs Important In King Tut’s Tomb?

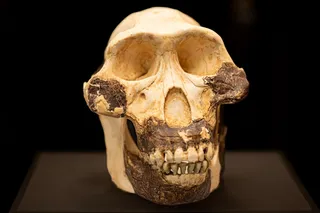

The scarab beetle was one of the most prevalent symbols of ancient Egypt, found in all sorts of tombs beyond that of Tutankhamun. While the symbol was ubiquitous, the use of rare gems shaped into scarabs would have been confined to super powerful and wealthy pharaohs like Tutankhamun, says Ikram.

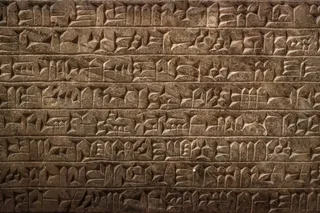

Scarabs adorned his tomb in a number of places, from the hieroglyphics on the walls to all sorts of jewelry—this was because it had so many symbolic meanings, says Aidan Dodson, an Egyptologist and historian at the University of Bristol. It’s also a symbol of the sun at sunrise and a symbol of coming into existence.

“The sun god Ra has four different forms, depending on the time of day. First thing in the morning [when the sun is rising], he is represented as a scarab beetle,” says Dodson.

The ancient Egyptians took the view that the scarab beetle pushing its ball of dung, which it is known to do in the wild, is seen as Ra pushing the sun over the horizon, Dodson says. We now know that dung beetles push their ball of excrement so they can use it as nutrition for their offspring, but the ancient Egyptians wouldn’t have known this.

The symbol of the scarab beetle means to come into existence or to continue to exist, which would have been important for a pharaoh hoping for a smooth journey into the afterlife. “In Egyptian mortuary beliefs, it would have meant continuity between this world and the next,” says Dodson. “The idea of coming into existence also symbolized the idea of rebirth in the next life.”

Scarab beetle amulets were also put into the wrappings of mummies. “The heart scarab was often used in mummification, and it was inscribed with a prayer to protect the heart so that one can enter into the afterlife safely,” says Ikram.

In the end, the ancient Egyptians often used natural phenomena like scarab beetles as metaphorical religious symbols. They looked to nature as almost godly. And the scarab was one of their most important symbols, used to show that one could be reborn again in the same way that the sun rises each morning.

Read More: We Celebrate King Tut, But He Was Once Erased From Ancient Egyptian History

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Salima Ikram. An Egyptologist at The American University in Cairo.

Aidan Dodson. An Egyptologist and historian at the University of Bristol.

Egypt Museum. Winged Scarab Pendant of Tutankhamun.

Britannica. Howard Carter.

J Stor Daily. The Discovery of King Tut’s Tomb.