What’s in a date? Strictly speaking, New Year’s Day is just an arbitrary flip of the calendar, but it can also be a cathartic time of reflection and renewal. So it is with one of the most extraordinary dates in the history of science, January 1, 1925. You could describe it as a day when nothing remarkable happened, just the routine reading of a paper at a scientific conference. Or you could recognize it as the birthday of modern cosmology–the moment when humankind discovered the universe as it truly is.

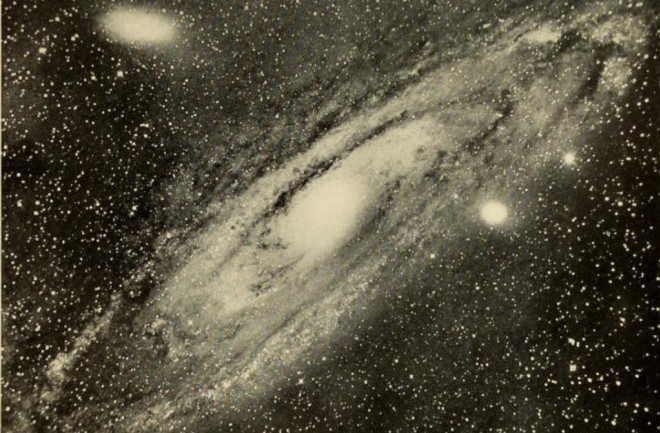

Until then, astronomers had a myopic and blinkered view of reality. As happens so often to even the most brilliant minds, they could see great things but they could not comprehend what they were looking at. The crucial piece of evidence was staring them right in the face. All across the sky, observers had documented intriguing spiral nebulae, swirls of light that resembled ghostly pinwheels in space. The most famous one, the Andromeda nebula, was so prominent that it was easily visible to the naked eye on a dark night. The significance of those ubiquitous objects was a mystery, however.

Some researchers speculated that the spiral nebulae were huge and distant systems of stars, “island universes” comparable to our Milky Way galaxy. But many others were equally convinced that the spirals were small, nearby clouds of gas. In this view, other galaxies–if they existed–were far out of sight, blue whales lurking in the far depths of the cosmos. Or perhaps there were no other galaxies at all, and our Milky Way was all there was: a single system that defined the entire universe. The dispute between the two sides was so intense that it prompted a famous 1920 Great Debate … which ended with an unsatisfying draw.

The correct picture of our place in the universe arrived just a few years later through the work of one of the most famous names in astronomy: Edwin Powell Hubble (no relation!). Starting in 1919, Hubble had established himself as one of the most patient and meticulous observers at Mount Wilson Observatory in California. Mt Wilson, in turn, had just established itself as the premier outpost for astronomical research, home of the just-completed 100-inch Hooker Telescope — then the biggest in the world. It was the perfect combination of the right observer in the right place at the right time.

Hubble also benefited greatly from earlier research by Vesto M. Slipher of Lowell Observatory, one of the unsung heroes of modern cosmology. Slipher had found that many of the spiral nebulae were moving at enormous velocities, far faster than those of any known stars, and that the spirals were mostly traveling away from us. To Slipher, those peculiar velocities provided convincing evidence that they must be independent systems, driven by unknown mechanisms at work far outside our Milky Way. But Slipher lacked the necessary resources to prove his interpretation. What he needed was a giant telescope like the one Hubble was piloting on Mt Wilson. This is where our story kicks into high gear.

Always cautious when it came to theory and interpretation, Hubble focused his scientific attention on the spiral nebulae without overtly endorsing the “island universe” interpretation. He preferred to wait until he could be the one to step forward with definitive proof — or disproof, if that’s where the evidence pointed.

In 1922, another important piece of the puzzle fell into place. That year, Swedish astronomer Knut Lundmark observed what he believed were individual stars in the arms of the spiral nebula M33. Shortly after, John Duncan at Mount Wilson spotted dots of light that grew fainter and brighter in the same nebula. Could these be variable stars, similar to ones in the Milky Way but far dimmer owing to their enormous distance?

Sensing the answer was at hand, Hubble stepped up his efforts. He spent long nights on his favorite bentwood chair, guiding the movements of the riveted-steel mount of the Hooker telescope to cancel out Earth’s rotation. The effort paid off with highly detailed, long-exposure images of the Andromeda nebula. The mottled light of the nebula began to resolve itself into a multitude of luminous points, looking not like a smear of gas but like a vast hive of stars.

Clinching proof came in October of 1923, when Hubble spied the telltale flicker of a lone Cepheid variable star in one of Andromeda’s arms. This type of star grows brighter and dimmer in a regular and predictable way, with its intrinsic luminosity directly related to its period of variation. Simply by timing the 31-day cycle of this star as it slowly flickered, Hubble could deduce its distance. His estimate was 930,000 light years–less than half the modern estimate, but a shockingly large number at the time. That distance placed Andromeda, one of the brightest and presumably closest of the spiral nebulae, vastly outside the bounds of the Milky Way.

In principle, the Great Debate was settled then and there. Spiral nebulae were other galaxies, and our Milky Way was just one outpost within a staggeringly vast universe. And yet, still the story was far from over.

Ever cautious, Hubble pressed on for more and better evidence. By the following February, he had uncovered a possible second Cepheid in Andromeda, Cepheid variables in M33, and possibly in three other nebulae as well. Now that there could be no doubt, he wrote to his arch-rival Harlow Shapley — a leading proponent of the idea that the spiral nebula were small and nearby — to needle him with the news. “You will be interested to hear that I have found a Cepheid variable in the Andromeda Nebula,” the letter began.

Shapley needed to read no farther to understand the significance of Hubble’s words. “Here is the letter that destroyed my universe,” Shapley morosely told Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, then a doctoral candidate at Harvard, who was in his office when Hubble’s missive arrived. (Payne-Gaposchkin was another pivotal figure in modern astrophysics; by remarkable coincidence, her pioneering work on stellar spectra was completed on … January 1, 1925!)

Despite his obvious excitement at the Andromeda findings, Hubble was still reluctant to publish his results. For all his surface confidence, he was terribly concerned about making a grand pronouncement prematurely. Every time he walked down from the summit to attend the formal 5 P.M. dinners at the Monastery, Mt Wilson’s living quarters, Hubble had to face his astronomer brethren. Not all of them accepted the existence of other galaxies. Vain and intensely aware of his reputation, Hubble worried that he might end up looking the fool.

Adriaan van Maanen, a playful and well-liked Dutch astronomer at Mt Wilson, was in fact still vigorously arguing in the other direction. He was convinced that he had observed some of the spiral nebulae rotating, which was possible only if they were relatively small and nearby. Hubble found it unsettling to have a doubter in his own midst and held back until he was utterly sure of his results. (Van Maanen never figured out where he went wrong and refused to admit his mistake. Hubble finally reexamined his colleague’s photographic plates and declared that “the large rotations previously found arose from obscure systematic errors and did not indicate motion, either real or apparent, in the nebulae themselves.” In academic terms, it was a fiery rebuke.)

Word of Hubble’s discovery inevitably leaked out to the media. As a result, the first public announcement of his astronomical breakthrough was a small story that ran in The New York Times on November 23, 1924. The single greatest cosmic discovery of the past three centuries therefore debuted as a buried news item!

Still Hubble balked at formal publication. The noted stellar astronomer Henry Norris Russell pressed him to present his findings to a Washington, D.C., meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which offered a $1,000 prize for best paper. When Hubble still didn’t submit anything, Russell snorted, “Well, he is an ass. With a perfectly good thousand dollars available, he refuses to take it.” Then Russell opened his mail to find that Hubble’s paper had just arrived.

Now and only now do we get to the stunning public reveal. On January 1, 1925, Hubble remained in splendid isolation at Mount Wilson while Russell read his revolutionary paper about the existence of other galaxies to an enthusiastic crowd. Hubble shared the best-paper prize. His paper ended the Great Debate, and did much more. It quickly increased the size of the known universe by a staggering factor of 100,000. It set the stage for the discovery of the expanding universe and, by extension, an initial Big Bang (already hinted at in the nebula velocities logged by Slipher). If any date can be said to be the birthday of modern cosmology, this is it.

Oddly enough, it was Shapley, not Hubble, who suggested that astronomers should adapt their nomenclature to the new reality and call the external star systems “galaxies.” Hubble still carried within him the conservative views of the world he overthrew. He was also naturally inclined to disagree with any idea that came from his rival, Shapley. So it happened that Edwin Hubble, the man who proved that the Milky Way is but one of innumerable galaxies, forever called the objects by the archaic name “extra-galactic nebulae.”

As Hubble watched the cyclical flaring and dimming of the Cepheids in Andromeda, he extended the reach of the human mind in yet another way. He erased the lingering concern that stars lying at great distances from us might behave differently from those in our immediate celestial neighborhood. Now that scientists could examine stars in other galaxies, they could establish the constancy of the universe over space and time as well.

By modern reckoning, the Andromeda galaxy is 2.5 million light-years away, which means the light we see now started on its way earthward 2.5 million years ago. That is, we are seeing the stars in Andromeda that are not only 2.5 million light years away, but also living 2.5 million years in the past. Nevertheless, they look identical to nearby stars. As Edwin Hubble and other astronomers looked out to ever greater distances, they added more and more evidence for the principle of spatial and temporal uniformity. All across space and time, atoms seem to give off the same light and variable stars seem to follow the exact same physical laws.

This constancy of nature lent credibility to the search for a single set of overarching cosmic rules. Or, as Albert Einstein might have put it, it showed that God does not change the house rules of the cosmos. That was one hell of a birthday present for the human mind.

Parts of this post are adapted from God in the Equation: How Einstein Transformed Religion by Corey S. Powell; Free Press, 2002.