Most college freshmen fill their dorm rooms with clothes, books, and electronics. Thiago Olson also brought his fusion reactor. But Vanderbilt University drew the line: No do-it-yourself reactors in the dorm! Instead, his device was housed in a nearby laboratory.

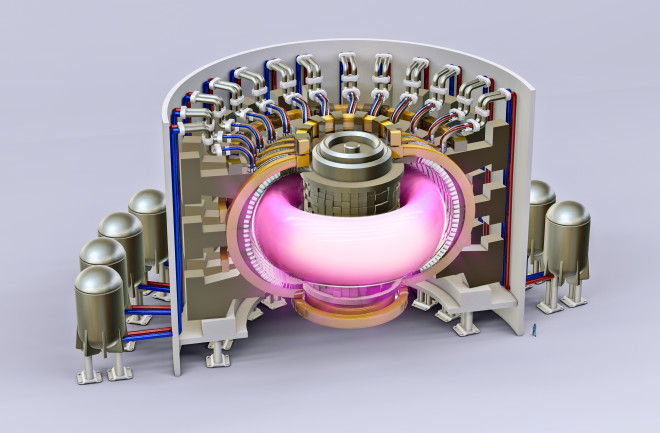

Olson’s project was motivated by the challenge of doing fusion—and by the same promise that has inspired thousands of physicists over the past half century. Nuclear fusion is the energy source that powers the sun; if channeled correctly, it could become a major source of clean energy here on Earth. Fusion occurs when the nuclei of two atoms are forced so close to each other that they bind together, releasing a great deal of energy in the process. Because positively charged nuclei forcefully repel each other, though, high temperatures are needed to bring about a union. Most fusion reactors are therefore enormous machines, like the $3.5 billion National Ignition Facility that recently opened in California.

Olson and a small cadre of other amateur nuclear engineers have found a simpler way. They are creating home-grown reactors, welding and wiring the devices in their backyards, garages, and basements (much to the alarm of neighbors). The hazards to the community are slim, the main ones being heavy use of electricity and short-range radiation that can be of risk to the “fusioneers” themselves. You can find out more about building a fusion reactor at www.fusor.net, an online community of fusioneers who help each other find parts, assemble, and problem solve. Also, check out a pair of books, Radiation Detection and Measurement by Glenn F. Knoll and Building Scientific Apparatus by John H. Moore.

If you decide to proceed, though, a few cautions: Beware of high-voltage electricity, which can skyrocket to more than 50,000 volts—enough that contact with a loose wire will kill you instantly. Pressurized flammable gas can also be fatal. And electrons hitting the stainless steel chamber produce X-rays, so do not look at the little window directly. Instead use a camera or leaded glass filter. Contact your state’s department of health for regulations. Your reactor will use a lot more energy than it produces. It is barely capable of achieving a detectable nuclear reaction, so fusion is one of the least hazardous parts of this project.

For those who would like to join in on the fusion fun, DISCOVER offers this guide to the essentials. With a lot of scrounging for cheap parts online or at scrapyards, plus a lot of elbow grease, it is possible to put together a fusion reactor for as little as $1,000. If you need fusion right now, though, you can pay retail and get what you need for about $20,000.

RADIATION DETECTION EQUIPMENT Prove that you really achieved fusion by using a bubble dosimeter, which provides instant visual verification and measurement of neutrons produced by fusion reactions. If you get bubbles, you did it! Price: $120

VACUUM CHAMBER Get a stainless steel chamber to seal your fusion particles in and to keep air out. Olson’s vacuum is made from an old mass spectrometer he found on eBay. You will probably need a lot of bolts to get the chamber closed tightly, and possibly a large flange for patching up a gaping hole, which can cost $500. If you are a student, try asking the manufacturer for a discount. Price: $300–$4,000

DEUTERIUM The atomic nuclei in the hydrogen plasma are what collide to create fusion inside the chamber. Deuterium, or heavy hydrogen, is found in seawater, but it is hard to separate from its far more common, lighter cousin. Its distribution is also tightly regulated due to its close ties to nuclear technology. Unless you have special connections, a business or university will need to request it on your behalf. Price: around $250 for 50 liters of gas in a lecture bottle

HIGH-VOLTAGE POWER You will need at least 20,000 volts* and a 10-milliamp current to create enough heat to crush those hydrogen nuclei together. Remember that because you are trying to attract positive deuterium ions, you want negative output, so you must ground the positive charge. Olson uses an X-ray transformer salvaged from an old mammogram machine. A commercial power supply by Spellman or Glassman is another option, or the intrepid electrician can make one from scratch. Price: $400–$10,000

VACUUM PUMP Suck all the unwanted particles out of the chamber. A two-stage roughing pump will get you to a near vacuum. Then use a turbo or oil diffusion pump to reach a high vacuum. Price: $350–$4,000

GAS REGULATOR Use this to inject tiny amounts of deuterium into the chamber and to regulate pressure inside your reactor. Needle valves can fine-tune the amount going in; capillary tubing (with an inner diameter as narrow as a pin) will really slow it down. If you can afford to, forget those and instead use a mass flow controller, which allows you to delegate the job to your computer. Price: $100–$200

* Correction, March 3: This originally read "50,000 volts."