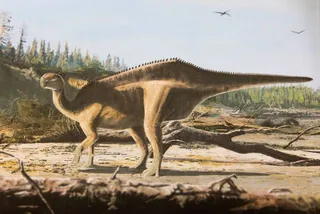

What do horses, armadillos, sloths, and tapirs all have in common? They’re all animals, sure. They’re all mammals, too. But there’s something more striking, more special, about them: Around 500,000 years ago, they all fell into the same sinkhole along Florida’s Steinhatchee River. Sediments filled their sinkhole thereafter, trapping them there until they were found, fossilized, in 2022.

Today, these animals provide insights into Florida’s Middle Irvingtonian Period, a forgotten age from which very few fossils have been found.

“The fossil record everywhere, not just in Florida, is lacking the interval that the site is from,” said Rachel Narducci, a collections manager from the Florida Museum and an author of a new study about the site in Fossil Studies, in a press release.

Researchers say that the abundance of horses at the site hints at what the landscape looked like around 500,000 years ago, while the assemblage as a whole ...