The moment of truth had arrived. In an arena in the Asia Minor city of Halicarnassus, a pair of gladiators locked in a fight to the death reeled across the sand, exhausted from parrying and charging, stabbing and feinting. Finally, unable to get the better of each other, the combatants slid off their polished bronze helmets and gazed defiantly toward the stands. In a box reserved for dignitaries, the wealthy sponsor of the games watched the spectators rise as one and demand mercy for the two women who stood before them, battered, bloodied, and bone weary, but still undaunted. Standing, the sponsor announced his decision: The lives of both women would be spared, at least until their next match. The event was subsequently memorialized by a sculptor who carved a handsome stone relief of the female gladiators, recording their names, Achillia and Amazon, and noting their rare reprieve. Exhibited today in a crowded gallery in the British Museum in London, the weathered marble from Halicarnassus depicts the trim and muscular women with swords drawn and shields hefted, poised for eternal combat. "Amazon and Achillia must have fought well," observes Ralph Jackson, a curator in the department of prehistory and early Europe at the museum. Amazon and Achillia are the only female gladiators whose exploits are known to have been sculpted in stone. But various chronicles reveal how bloodthirsty Roman crowds delighted in watching women fight each other in the ring. Early in the first century A.D., the emperor Nero, a man famed for his personal debaucheries, forced the bejeweled and cosseted wives of Roman senators into amphitheaters, presumably to take up swords against each other. Matches between female slaves were staged by the emperor Domitian, who ruled from A.D. 81 to A.D. 96, and gained in popularity over the years. Historical texts suggest the emperor Septimius Severus outlawed the spectacles in A.D. 202, but scholars suspect they continued for some time afterward.

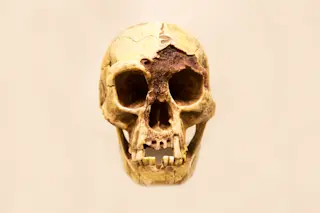

Although women risked life and limb as gladiators for more than a century, evidence of their activities remains rare. Roman writers focused on the lives of men, penning only sketchy accounts of women in general, much less women on the fringes of society. In recent months, an intriguing archaeological find in Great Britain has added to the mystique of female gladiators. The discovery of what might be the remains of a female gladiator on the far outskirts of the Roman Empire has sparked a lively debate among scholars about women who participated in the popular blood sport and their status in the ancient world. A curiosity about the exploits of female gladiators seems oddly out of character for archaeologist Hedley Swain, a short, slim, compact man of 40 with a smile full of crooked teeth and an affinity for conservatively tailored suits and ties. Swain is the head of the Museum of London's early history department, where he is in charge of a pile of ashes and bone fragments dubbed Gladiator Girl by the British press. Unearthed from one of the most ancient addresses in Roman London, this 1,900-year-old woman has yet to reveal many secrets. The circumstances of her life and death are largely unknown. But Swain, for one, thinks it's possible she was a former slave turned wealthy female gladiator. A routine inspection by the Museum of London's archaeologists of a building site on the outskirts of the old city led to the discovery of the woman's remains. No sooner had the team begun sinking test pits at Great Dover Street, in the Southwark district, than they stumbled on a graveyard from an era when London was a remote outpost of the Roman Empire. "It was Roman law that you couldn't bury the dead within town boundaries," says Swain, "so you'd have the cemeteries outside, and it was a custom to put them along the main roads." As the archaeological excavation expanded, the team found a wealthy Roman's grave situated on the periphery of the cemetery, the kind of spot where a social outcast might be buried. Yet the grave's inhabitant seemed no pariah. Mourners had lovingly dug a large pit and arranged timbers over it to make an impressive pyre. Then they had laid the corpse upon it and lit a fire. As the flames died, burnt fragments from the cremated skeleton toppled down into the pit, where mourners left remains of a costly funerary feast and arranged a trove of lamps and large tazze, or incense burners. Then they covered it all in a thick layer of earth. The elaborate burial posed a mystery. If the dead person was persona non grata, why had a wealthy circle of mourners taken such trouble? Specialists at the Museum of London began sifting through soil, plant, and faunal samples recovered from the grave. Osteologist Bill White pored over the cremated human bone. Some of the larger fragments clearly came from the pelvis—a stroke of luck in terms of sexing the body. While the male pelvis is deep and narrow, the female pelvis is shallow and wide and contains many sex-specific features. From an analysis of the charred fragments, White concluded that the body belonged to a young woman in her twenties. In other laboratories, botanist John Giorgi and faunal analyst Kevin Rielly began scouring for clues to the woman's last rites. The mourners, it seemed, had filled the incense burners with the sweet-smelling cones of the stone pine, a conifer native to Italy. Someone had even paid for a lavish farewell feast of doves, chickens, and imported figs, dates, and white almonds from Mediterranean groves. Everything spoke of wealth, power, and refinement. Tiny traces of molten glass the young woman had been wearing glittered in the grave fill.

Who, Swain wondered, would have lived as a pariah and yet attracted wealthy admirers? One of the four picture lamps intended to light the woman's way to the next world offered a clue. The image engraved on the lamp was a fallen gladiator. In Roman society, gladiators were bought and sold as slaves and condemned to become contract killers in the ring. But the Romans worshiped courage. They paid unabashed homage to anyone who displayed valor. Emperors issued coins stamped with the faces of popular gladiators, and wealthy families decorated homes with scenes of their death agonies. To Swain and others on his team, the gladiator picture lamp suggests that the Great Dover Street woman may have been one of these revered fighters. In addition, the other three picture lamps in the grave featured rare Roman images of Anubis, the Egyptian god of the dead. Anubis, Swain says, was the Egyptian counterpart of the Roman god Mercury, who conducted the souls of the dead to the next world and played a key role in Rome's amphitheaters. "Slaves dressed as Mercury would actually be present in the gladiatorial ring and remove the dead gladiators," he says. The mourners' unusual choice of stone-pine cones as incense added further credence to the team's theory. The stone pine was not native to Britain. It was, however, indigenous to Italy, where Roman citizens frequently planted it around local amphitheaters: The tree's fragrant cones are thought to have helped cloak the nauseating stench inside. The fragrant perfume of the stone pine would have made a fan's fitting farewell to a popular female star of the arena. The researchers are certain of one thing: Gladiatorial spectacles were all the rage in Roman London. Two years ago a team of 50 researchers from the Museum of London Archaeology Service completed a detailed, decade-long excavation of fragmentary ruins from the site of a first-century amphitheater uncovered in London's Guildhall section and came up with an astonishing estimate of the arena's seating capacity. The massive oak structure would have accommodated 6,000 to 7,000 people—in a city with an estimated population of 20,000. "That's one out of every three people," says archaeologist Nick Bateman, who supervised the dig. "The population of London today is about 7 million people. Imagine a spectacle that attracts nearly 2.5 million people. That makes it incredibly important." To Swain, the diverse pieces of evidence add up to an intriguing whole. It's quite possible, he says, that the Great Dover Street woman made her name in the arena. "This woman, a professional gladiator, comes to London from somewhere in the Empire," he suggests. "She has a following of people, or is part of a group of people, and is killed or dies, and is buried at the very edge of Roman London, outside the boundary but with these symbols of her profession, including the pinecones and the lamp. So that, as you like it, is the case for the gladiator."

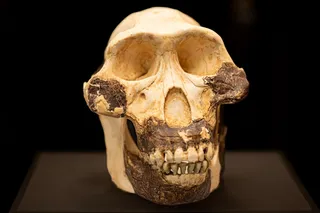

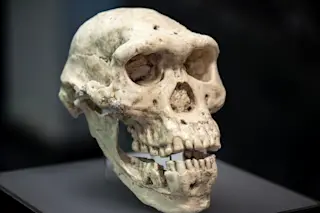

Critics argue that Swain's interpretation is based more on fancy than fact. Kathleen Coleman, a professor of Latin at Harvard University and an expert on gladiatorial spectacles, sees problems with one of the key pieces of evidence—the gladiator lamp. Pottery makers, she says, mass-produced gladiator lamps; they were sold as popular household items. "I think the very most you could say is the presence of gladiatorial images on some grave goods might suggest that the deceased or a member of the deceased's family was a gladiatorial fan." Coleman also doubts that any gladiator, no matter how revered by fans, received such a costly send-off to the next world. Gladiators lived on the fringes of society, and "it seems a stretch to assume that one would have been buried in what appears to be quite a lavish way," she says. "We know that Roman charioteers could often amass enormous fortunes, but we don't have any hard evidence for a specific patrimony associated with a gladiator." Leaning back in his chair in his Museum of London office, Swain concedes that the enigmatic grave on Great Dover Street is open to other interpretations. It is quite conceivable, he suggests, that the mysterious young woman was nothing more than a wealthy, headstrong follower of an obscure Egyptian cult whose members buried her with all the pomp and ceremony required by their particular religious beliefs. But he also points out that the female-gladiator argument is built on the sum of the evidence, which is greater than the individual pieces. "No single piece of evidence says that," he notes. "There's simply a group of circumstantial evidence that makes it an intriguing idea." While Swain and his colleagues in London puzzle over the artifacts discovered in the Great Dover Street grave, researchers elsewhere are beginning to shed light on the way in which female gladiators once fought. In a castle near the small German town of Elsendorf, just an hour's drive from Munich, military historian and experimental archaeologist Marcus Junkelmann has spent the past four years examining Roman depictions of gladiators in order to re-create ancient weaponry and glean new insights into the extreme nature of the sport. Roman audiences, he says, craved novelty. To entertain them, gladiator troupes featured a dazzling assortment of fighters, from nimble lightweights known as the retiarii, who danced around the arena with tridents and nets, to heavyweights called the murmillones, who plodded across the sand with swords and heavy shields. On rare occasions, he says, troupes reportedly staged fights with female combatants. Given the smaller frames and lower muscle mass of women, one might expect that female gladiators assumed lightly armed roles in the ring. But the marble relief of Amazon and Achillia suggests that at least some women took up heavy arms. Halicarnassus's famous pair bears burdensome shields and leg protectors associated with a specific class of middleweight fighters: "I think they are provocatrices," says Junkelmann. To learn exactly how these and other gladiators fought, Junkelmann and his colleagues at the Regional Museum of the Rhineland, Treves, analyzed dozens of pieces of authentic Roman armor, much of which had been preserved in the ancient Italian town of Pompeii. Abandoned in A.D. 79 during the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii has attained a tragic immortality beneath a thick blanket of ash and pumice. While tunneling there in the 18th century, antiquarians had stumbled upon an entire gladiatorial barracks, whose floors were littered with ornately decorated helmets and a small trove of leg and shoulder guards, shields, and swords left by fleeing gladiators.

Junkelmann set to work replicating this gear. He photographed each piece of armor, then weighed them and measured their dimensions. He searched out existing reports on their metallurgical content. Back in Germany, he and his museum colleagues collaborated with five craft specialists, who began forging exact replicas of the armor and weapons. It was a tricky business, because modern-day materials vary noticeably from those of the Romans. The gleaming bronze in one Roman helmet, for example, resembles modern brass, not modern bronze. Junkelmann recruited a team of martial-arts experts and history buffs to train as gladiators. As the troupe became increasingly skilled, they began to discern the clever design of the armor. The large, heavy helmets with their imposing visors were exquisitely balanced, imposing little strain on the neck. Moreover, the armor makers had deliberately left the gladiators' torsos bare but guarded them from maiming injuries. "You needed to have bodies that were vulnerable but also well-protected in certain places," says Ralph Jackson of the British Museum. "If the limbs especially, but also the head, were struck at an early stage, the event would be a damp squid. So you had to have very secure guards for the head and legs." As provocatrices, Amazon and Achillia seem to have donned nearly 30 pounds of armature, including a heavy shield constructed of birch and lined with felt. To protect their sword arms, they wore either a linen or segmented-metal arm protector called a manica. "Anyone who has ever tried fighting with shield and sword," notes Junkelmann in a recent article, "will know that an unprotected sword arm is very soon black and blue and running with blood, not so much from an opponent's weapon as from colliding with the edge of your own shield and his." In addition, the two women apparently strapped on short bronze leg guards and donned visored helmets over heavy felt linings. "Most armor demands padding," explains Peter Connolly, a military historian and an expert in gladiatorial gear based in Spalding, England. "The metal won't protect you from the blow, and this is particularly so with helmets. If someone belts you along the head, the helmet might stop the blow, but it will knock you out." Such a cushion came at a cost, however. The felt linings absorbed heat. "The gladiators must have been absolutely rolling in perspiration," says Connolly. "It must have been dreadful." Amazon and Achillia's weapon of choice was a small, straight-bladed sword. Designed for stabbing or thrusting, it imposed a specific style of fighting. Instead of fencing or swooping around an opponent with a high, wild, slashing motion, says Junkelmann, the women would have concealed their swords behind their shields, each trying to take the other off balance and lunge forward in a surprise attack. "You have to be more aggressive than defensive, waiting your chance," says Junkelmann. "And in the end this is more thrilling than the other, berserk style of fighting." Historical records show that Roman gladiators generally clashed in pairs, one duo at a time; the matches were relatively short but furiously intense. Classical scholars calculated that the average contest lasted just 10 to 15 minutes, based on an analysis of records of the numbers of gladiators hired for particular afternoons in Rome's amphitheaters. Junkelmann's experimental matches confirmed this estimate. After five or 10 minutes, heavily armed combatants panted with exhaustion.

One of the most intriguing discoveries, however, was also one of the most unexpected. The visored helmet tended to depersonalize the combatants. "When you have someone in front of you, without a face, it's like a monster," notes Junkelmann. "You have a different feeling than you would if you fought with someone whose face is visible." In all likelihood, such anonymity made for fiercer fighting. Roman accounts show that the sponsors of games frequently rented out all the day's gladiators from only one troupe. As a result, combatants knew each other well, after living together for weeks, months, or even years as comrades in arms. Without the anonymity created by face visors, many may have found the task of dispatching their opponents unbearable. In amphitheaters scattered throughout the Empire, Romans delighted in discussing the finer points of gladiatorial matches. Professional contests, after all, were neither executions nor bloodbaths: They required immense skill from combatants, as Junkelmann's experiments show. Accustomed to such finesse, Roman fans were unlikely to be satisfied by the flailings of untrained fighters. As classicist Mark Vesley points out, this public appetite for professional gladiators raises an important question: Where did women, particularly thrill-seeking patricians, learn to take up arms? Traditional gladiator schools were fit only for slaves and social outcasts. Vesley, a Roman social historian at St. Thomas University in St. Paul, Minnesota, speculates that some women may have studied under private tutors. Others, he suggests, may have enrolled in the collegia iuvenum, Roman clubs that resembled a cross between the Boy Scouts and the ROTC. Open to all young male nobles over the age of 14, these clubs supplied gymnastic, athletic, and martial-arts instruction. "That's the logical place where anyone who was not a slave or a criminal would have got the martial-arts training needed to put on a credible performance in an arena," says Vesley. Combing through all known inscriptions relating to these clubs, Vesley found mentions of young women in three of the texts. The most telling was the most concise and poignant. It read, "To the divine shades of Valeria Iucunda, who belonged to the body of the iuvenes. She lived 17 years, 9 months." Like Amazon, Achillia, and the woman buried at Great Dover Street, Valeria Iucunda's life will forever resist greater scrutiny. "This is the kind of evidence we often have to go on when we are trying to say something intelligent about women in the ancient world," says Vesley. "It's incredibly scrappy." One can only imagine the flash of iron in an arena, the quick and desperate struggle at close quarters, and the savage clamor of a baying crowd intoxicated by the sight of blood. Web Resources

Learn about female gladiators at the Classics Technology Center's site: ablemedia.com/ctcweb/consortium/ gladiator6.html. See Current Archaeology's site at www.archaeology.co.uk/issues/ ca158/intro158.htm to learn more about Roman London. Check out updates from the Museum of London Archaeology Service at www.museum-london.org.uk/MOLsite/menu.htm.