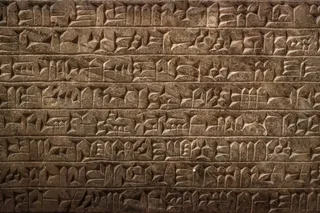

Thanks to archeological discoveries, we’ve been able to learn invaluable information about many facets of history. Which life forms existed, how they lived, and how and when they died have emerged because of evidence unearthed by archeologists and other scientists. The Rosetta Stone, the Dead Sea Scrolls, King Tutt’s Tomb and the ruins of Pompeii are some of the most well-known. Within the last decade alone, archeologists have made some major discoveries. Let’s look at five of the most interesting archaeological discoveries of the last 10 years.

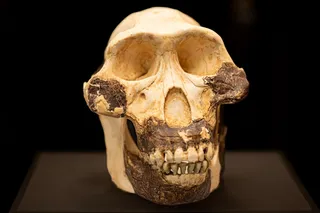

When King Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, he was buried in the church of the Grey Friars. In 2012, The Richard III Society collaborated with the University of Leicester to excavate under a Leicester parking lot to look for the church — which they found. But even more shocking was that they also discovered human remains thought ...