For many people in the ancient world, life was no casual stroll around the Forum. Today, many diseases can be treated with modern medicine or prevented entirely, thanks to the development of myriad vaccines to help rid us of the risk of infection (though major inequalities still mean such lifesaving shots are not available to all).

In ancient times, however, these advances simply were not available, making disease an ever present and deadly risk. Kyle Harper, professor of classics and letters at the University of Oklahoma, says that in ancient times life expectancies were so low in part because infectious diseases were such a powerful force.

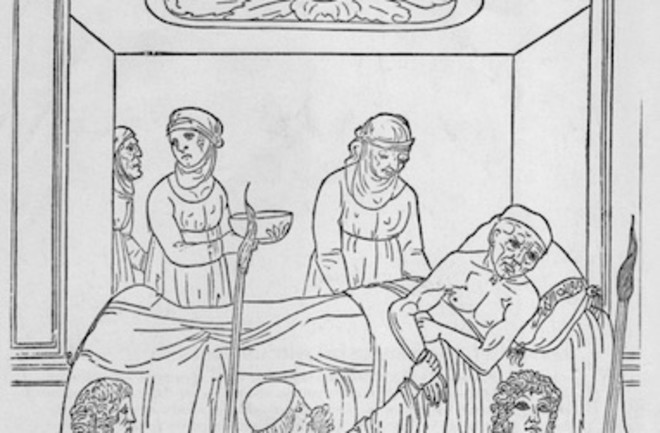

“They didn't have the biomedical and public health resources that we enjoy today,” he adds. Healthcare to some degree did exist in the ancient world and medical advances were made, but treatment often revolved around dubious remedies, charms, and superstitions.

“The class of diseases that are caused by some kind of microbial invader were one of the most fundamental facts shaping every premodern society,” Harper says.

Tuberculosis and Malaria in Ancient Times

Today, the average global life expectancy is around 70 years of age and continues to increase, but centuries ago, that was hardly the case. In ancient Egypt, it’s believed that the average age at death was as low as 19, mainly due to high infant death rates. The average lifespan of a man is thought to have been around 25. In ancient Greece and Rome, people fared little better as some estimates place the expectancy range between 20 and 35 years.

Attributing to these low life spans, many of the diseases that ancient peoples faced are still recurrent health problems today. Tuberculosis, for example, has ravaged human populations for thousands of years. Egyptian mummies from around 2400 B.C.E. show deformities similar to TB and ancient texts from China and India may refer to it, according to research.

The disease was known as phthisis to the ancient Greeks and the physician Hippocrates reports that many in his homeland succumbed to the illness. Today, over a million people continue to die of TB each year, even though it is both curable and preventable.

Malaria too was likely endemic in ancient Egypt and Nubia, alongside other diseases such as leishmaniasis and schistosomiasis. Two mummies buried around 3,500 years ago likely died of malaria, making them the two earliest known cases of the mosquito-borne disease.

It’s also known that malaria was prevalent in certain regions of the Roman Empire and DNA evidence shows that the malaria was present across Italy in ancient times.

Read More: What Is Hydrophobia and What Causes It?

A range of other diseases hammered ancient civilizations, including cancer, which Hippocrates described, ultimately giving it its name. Similarly, one of the first descriptions of rabies dates back to Greece around 500 B.C.E.

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder describes how those who are bitten by dogs with “canine madness” develop a deadly horror of water, and outlines curious remedies to combat the disease.

Parasites and Pandemics

On top of this massive health burden came others, such as gastrointestinal diseases and parasites such as worms, the impact of which are easy to underestimate, says Harper. Studies indicate that people living in the ancient world were regularly exposed to and riddled with different kinds of intestinal worms.

Read More: The Biggest Parasite Can Grow Up to 30 Feet Long, and Live in Your Stomach

Pandemics also rocked the ancient world. Back in 430 B.C.E., a plague hammered the besieged city of Athens. Over the course of three years, it’s estimated that as many as 100,000 people may have died, representing around one quarter of the city’s population at that time. What caused this particular plague remains somewhat of a mystery.

“The Roman world seems to have experienced a number of really explosive, consequential pandemic disease events,” adds Harper, who has authored books on that same subject.

The Antonine Plague – which occurred between 165 and 180 C.E. – is estimated to have killed around 2,000 people per day in Rome at its peak, even claiming the life of Lucius Verus, co-emperor alongside Marcus Aurelius. It’s unclear what caused the outbreak, says Harper, but suggestions include measles or an ancestral form of smallpox.

Similarly, the Plague of Cyprian occurred between 250 and 270 C.E. It originated in Ethiopia before spreading across the Mediterranean region and beyond; its death toll may have reached as high as 5,000 people per day in Rome, according to estimates. Like the Antonine Plague before it, there is speculation about its cause.

Harper says that it may have been viral hemorrhagic fever, while other possibilities include typhus, measles or meningitis. “Until we get DNA evidence, we are going to have trouble saying what caused the plague,” he notes.

Another Plague, Same as the Black Death

Such evidence does exist for the later, and far more devastating, Plague of Justinian. This erupted in 541 C.E. and continued to claim lives across the Mediterranean for over 200 years.

“The Plague of Justinian in the 540s is the only one where we know with absolute certainty what caused it,” Harper says. “It was bubonic plague.”

Spread by black rats, this plague is the same culprit behind the infamous Black Death that rocked Medieval Europe between 1347 to 1351, killing millions of people. Harper describes it as “the most explosive pandemic disease in human history.”

By the time the outbreak ended, it’s believed that between 25 to 50 million may have died across the Mediterranean, though this is debated.

Read More: Scientists Reveal the Black Death’s Origin Story

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diseases You Almost Forgot About (Thanks to Vaccines).

Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future.

World Health Organization. Vaccine Equity.

World History Encyclopedia. Medicine in the Ancient World.

World Health Organization. GHE: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy.

World Economic Forum. Charted: How life expectancy is changing around the world.

University College London. Old age in ancient Egypt.

Kelsey Museum. Life, Death, and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt.

Frontiers. Editorial: Health related quality of life inequalities.

Journal of preventive medicine and hygiene. The history of tuberculosis: from the first historical records to the isolation of Koch's bacillus.

American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. The Masterful Description of Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Soranus of Ephesus (c. 98–138 A.D.).

World Health Organization. Tuberculosis.

Britannica. Malaria through history.

Parasites & vectors. The history of leishmaniasis.

Journal of advanced research. Epidemiology of Schistosomiasis in Egypt: Travel through Time: Review.

Emerging infectious diseases. Plasmodium falciparum in Ancient Egypt.

Oxford Academic. Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy.

Current Biology. Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 1st–2nd century CE southern Italy.

Hippokrates. [Diseases in the ancient world].

American Society for Microbiology. The Ancient Curse: Rabies.

International Journal of Paleopathology. Gastrointestinal infection in Italy during the Roman Imperial and Longobard periods: A paleoparasitological analysis of sediment from skeletal remains and sewer drains.

The Mount Sinai journal of medicine. The plague of Athens: epidemiology and paleopathology.

Princeton University Press. The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire.

World History Encyclopedia. Antonine Plague.

Britannica. Lucius Verus.

World History Encyclopedia. Plague of Cyprian, 250-270 CE.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What are VHFs?

Britannica. Black Death.