As a small child perusing old physical anthropology books I would occasionally stumble upon images of people of Oceanian stock with light hair color. I would wonder: is this a biological or cultural feature? In other words, were people bleaching their hair? If it was biological, was it heritable, or was it simply malnutrition? Another aspect of the phenotype was also straightforward: it did not seem that light hair color resulted in any concomitant lightening of the skin. Granting that this was a heritable biological trait, the questions then were simple: was this trait an independent occurrence of de-pigmentation in Oceania, or was it due to introgression of European alleles?

First, one must note that this is not an isolated feature in Oceania. Rather, blondism crops up in the Solomon Islands, in New Guinea, as well as among some Australian desert groups. This in itself should make us skeptical of the model of European admixture. Additionally, blue eyes, which exhibits a higher frequency in Europeans than blonde hair, is not similarly common in these populations. But all this speculation is now a historical curiosity. The results are widely known from conference presentations that have been reported, but finally the paper is out in Science which solves the “riddle” of hair color in Oceania at the level of genetic causation.

Melanesian Blond Hair Is Caused by an Amino Acid Change in TYRP1:

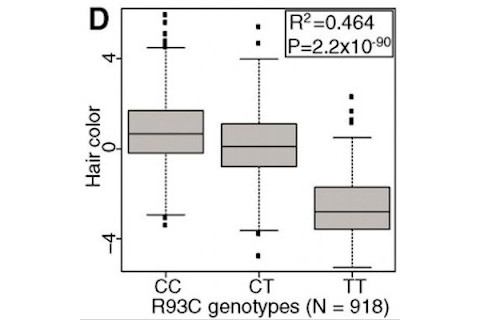

Naturally blond hair is rare in humans and found almost exclusively in Europe and Oceania. Here, we identify an arginine-to-cysteine change at a highly conserved residue in tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP1) as a major determinant of blond hair in Solomon Islanders. This missense mutation is predicted to affect catalytic activity of TYRP1 and causes blond hair through a recessive mode of inheritance. The mutation is at a frequency of 26% in the Solomon Islands, is absent outside of Oceania, represents a strong common genetic effect on a complex human phenotype, and highlights the importance of examining genetic associations worldwide.

(Credit: Kenny et al. 2012 Science)

Kenny et al. 2012 Science

The study was a classic cases vs. controls GWAS. They looked at variants in a lot of people with the trait, vs. those without the trait. Additionally, if you check the supplements and read the text it’s obvious there is no population straification. That is, having blonde hair is not correlated with a different ancestry in these Melanesian populations. Rather, this is a relatively robust recessively expressed trait that seems to have been segregating within these groups before contact. Those individuals who are homozygotes tend to have blond hair, while those who are not tend not to have blonde hair. TYRP1 is a pigmentation related locus, so it isn’t surprising that the mutation was around that region of the genome. The key though is to note that the specific mutation is not found in Europeans. Rather, it is limited to Oceanians. The extremely close correspondence between the genotype and the trait, and the lack of similarity in the variants between Europeans and Oceanians, ends debate on questions of the heritability and possible exotic origin of the trait in Oceanians. Now it is known, and the debate shall end.

So how did the Oceanians come to have such a high frequency of this trait? Here’s a comment from one of the preeminent biological anthropologists of Melanesia:

The mutation, which has no obvious advantages, likely arose by chance in one individual and drifted to a high frequency in the Solomon Islands because the original population was small, says Jonathan Friedlaender, an anthropologist emeritus at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the study. “This whole area seems to have been populated by very small groups of people making it across these stepping-stone islands, so you do have very dramatic effects in fluctuations of gene frequency.”

It is absolutely correct that Oceanian populations exhibit a lot of evidence of small effective population, and so are subject to random genetic drift. In this model the frequency of ~0.25 for the allele which results in bondlism in the homozygote in the Solomon islands is high as it is due to a drift event up in frequency from an initial variant mutation. But there are reasons I am skeptical of this. The first is a somewhat technical one: if the high frequency in the Solomons is due to rapid rise in frequency due to large generation-to-generation fluctuations, you’d expect to see some linkage disequilibrium in the region of TYRP1. That’s because presumably the blonde allele comes from a common ancestor, which just happened to be over-sampled in a high drift regime. Even if it wasn’t a selective sweep, flanking SNPs would still be transmitted at high frequency with the causal variant through drift. If the drift event occurred in the past, the allele should be fixed, or, it should be extinct. If you imagine that it was fixed in some populations, and then admixture resulted in the allele segregation, then there should be LD around the SNP too.

It is noted in the text that the authors did not find evidenc of high LD in their tests for natural selection, XP-EHH or iHS. These tests are cued to pick up relatively recent selective events, on the order of ~10,000 years or so. They’re geared toward detection of correlations of variation across regions of the genome generated by positive selection (though as I suggest above, they can also yield false positives due to stochastic events, especially iHS). Additionally, using Fst, a between population genetic variation measure, the authors note that the SNP in question has a high Fst when comparing Solomon Islanders with non-Oceanians, but nearby SNPs to it do not.

But there’s a very good reason I never expected there to be recent selection driving this anyhow: Australian Aboriginals sometimes manifest blonde hair, and the best genetic data suggests separation from Melanesians of at least 10,000 years.Additionally, the Solomon Islands were not part of Sahul, so that’s a conservative estimate. We don’t know if the Aboriginals have the same TRYP1 mutation, but there’s the same tendency toward dark skin and light hair amongst them. It also seems rather suspicious to me that the highest frequency of blonde hair outside of West Eurasia is all amongst Oceanian populations, who are phylogenetically a distinct clade.

What I am suggesting then is that this pigmentation mutation is an old feature of the Oceanian populations, on the order of tens of thousands of years. That is why there isn’t LD around this region; any LD which existed was long ago eliminated by recombination. But why is it still around at minor allele level frequencies? When all other explanations are found wanting, you go where you have to, so therefore I suggest some form of balancing selection. One could posit overdominance on a trait other than pigmentation, with the hair color being simply a correlated response.

Finally, I want to note that this really does confirm that as an overall trait controlled by a relatively small number of genes pigmentation in the lightening direction has a huge mutational target on it. Remember that East and West Eurasians are light skinned for different reasons. And in regards to skin color, an interesting point is that Melanesians, in particular Solomon Islanders, are amongst the most genetically similar to Africans when it comes to variation on these loci. TYRP1 is quite the exception.

Citation: DOI:10.1126/science.1217849

Citation: DOI:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00341.x