I have been living in Hawaii for six years now, and I have once, and only once, caught a glimpse of the snakes that call these islands home.

Meet the brahminy blindsnake, the only snake species to have successfully established in Hawaii. Photo by Mark Yokoyama. Yes, you read that right: there are snakes in Hawaii. Technically, there are two species that can be found here, but the yellow-bellied sea snake is so rare it almost doesn't count. The other — the brahminy blindsnake — is actually quite common, though it's easy to understand why it's often overlooked: these small, black creatures only grow to be about six inches long and dwell in the dirt. They are often mistaken for worms because of their diminutive size and underground lifestyle. The same species can be found worldwide: natively throughout Asia and Africa and non-natively in several places, including Hawaii. They're also the only species of snake that is entirely parthenogenic — no male has ever been collected. They simply don't look or act like we think a snake should. And now, scientists have documented yet another trait that makes them stand out from their serpentine brethren: before swallowing, they will sometimes decapitate their meal. Most snakes, whether they kill with venom or constriction, swallow their food whole (they even have amazingly flexible jaws to swallow things bigger than their heads!). They do so by orienting the prey item so that it goes down their gullet head first, then working their gymnastic jaws around the body inch by inch until the meal is entirely swallowed. It simply makes sense to eat your meal in one piece when you lack appendages to grasp or tear with. But then again, the brahminy blindsnake is not most snakes. They belong to the infraorder Scolecophidia, a more ancient group than the species we commonly think of as snakes. Scolecophidians are called "blindsnakes" or "thread snakes" because their subterranean lifestyle has led to reduced eyes and an incredibly thin, elongated body. There are only about 400 species of them in the world, as compared to the 3,000 or so other snakes. But at least one — the brahminy blindsnake, Indotyphlops braminus — had made up for a lack of diversity by taking over the world. And to date, this species is one of only five snake species known to break apart their meal before they consume it. It was a discovery made by Japanese scientists while they were studying the animal's feeding behavior. The team, Yosuke Kojima from Kyoto University and Takafumi Mizuno, a student at Kyoto Institute of Technology, wanted to study blindsnake feeding because the animals are known to gorge themselves when they eat, according to fellow herpetologist Andrew Durso. Individual blindsnakes have been documented eating more than 1,000 prey items in a single feeding! Such gluttonous behavior is uncommon in snakes, and the team were interested in understanding it better. But when they fed termites to one of the wriggling serpents they noticed something strange.

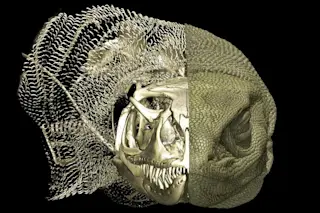

"Off with his head!" — a blindsnake has her meal Queen of Hearts-style. From Video S1, Mizuno & Kojima 2015 Instead of swallowing the termites head-first, like any respectable snake would, the blindsnake started from the termite's backside. Then, when only the head remained to be swallowed, the snake began to move its head back and forth, rubbing what remained exposed of the termite against the enclosure, until the head came clean off. The team kept feeding termites to the snakes, and about 50% of the time, they repeated this strange beheading ritual. Never did they eat the severed heads. Whether they removed the head or not, it took the snakes about 3 seconds to swallow each termite if they ate them rear-first. Sometimes, when the snakes had downed the termite whole, they would puke it back up just to remove the head and re-consume the body. Very rarely, the animals would eat the whole termite head-first, and when they did so, they swallowed their morsel almost twice as quickly, which just seemed even more strange. After all, when you're eating hundreds of termites in a sitting, speed is your friend — why waste time playing guillotine? That they spend so many extra seconds on head removal suggests there's a strong benefit to the behavior. There's some possibility that termite heads contain toxins, but since the snakes survive eating roughly half of them anyway, it's not likely they're very susceptible to such poisons. Instead, the scientists noted that the noggins which were eaten often came out the other end, in the animal's feces, implying that they aren't digestible. So it's likely the snakes avoid eating the heads when they can because they take up valuable space that could be packed with nutrient-rich food. Prior to this study, there were only four species of snake that have ever been seen dismembering their prey. Two species of Asian crab-eating snakes (Gerarda prevostiana and Fordonia leucobalia) have mouths too small for their hard-shelled meals, so they tear the crustaceans' legs off one by one. Another blindsnake, Epictia phenops, reportedly sucks out the insides of termites after decapitating them, leaving the skins and heads behind. And yet other blindsnake, Rena dulcis, was documented performing a similar rub-removal of termite heads back in 1963, though no one followed up on it. The authors think that the behavior may be more common than previously realized, as it's easy to miss and the blindsnakes are understudied as a whole. It's possible that many (if not most or all) of the Scolecophidians will behead their prey when it suits them. "Taken together with the previous reports," the authors write, "our study implies a possibility that prey-breaking behavior might be widely used among arthropod-eating, basal snakes." But until further studies are conducted, I. braminus remains one of few snakes that gives their prey the Marie Antoinette treatment. And just think — this gruesome act has been going on right under our noses all over the world and it took this long to notice. Which just goes to show that the closer we look at the life around us, the more we realize that even the most mundane-seeming species can surprise us. Citation: Mizuno, T. and Kojima, Y. (2015), A blindsnake that decapitates its termite prey. J Zool. doi:10.1111/jzo.12268