A few weeks back I blogged about SETICon, the first-ever conference held around the central theme of the search for intelligent life "out there" -- not quite a science conference, but not really a sci-fi convention either. SETICon was not only unique, but it was also a blast. Bring on SETICon II! Despite years of searching, Klingons and Asgard, Daleks and Vorlons are still firmly entrenched within the realm of science fiction -- for not only do we know of no intelligent life in our galaxy outside of that on Earth, we know of no life period. Finding even a microbe would be huge. (The find would be huge, the microbe would be small -- hence the "micro" portion of the word. We have no expectation of finding gargantuan Martian astronaut-sucking amoebae, as in Angry Red Planet.) While we may have to look to the stars for signs of intelligence,

the search for life is a somewhat different -- though obviously related -- matter and we shouldn't forget that there are many potential abodes of life within our own Solar System. Surprisingly many are in the outer solar system, and receive only a faint glimmer of Sol's life-giving radiation. Given the diversity of extremophile organisms discovered in the depths of Earth's oceans (like the tube worms at right) -- as well as other places that would initially seem counter-intuitive -- organisms that live their entire lives never seeing a single photon from the Sun, it appears that the presence of liquid water is much more of a requirement for life than is sunlight. Planetary scientists now have strong evidence to support the presence of oceans of liquid water under the icy crusts of outer Solar System moons like Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede orbiting Jupiter, as well as Saturn's Titan. For large Jovian moons, subsurface oceans seen to be the rule, rather than the exception.

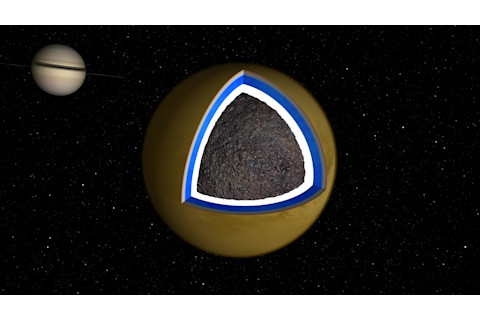

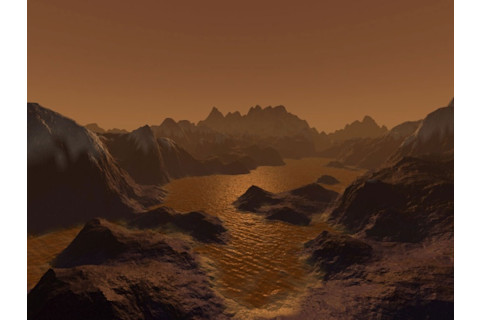

Cross Section of Titan. Image credit: NASA Titan, in particular, raises eyebrows. The moon is slightly larger than Mercury, and the instant Gerard Kuiper confirmed that this moon had a methane-rich atmosphere back in 1944, Titan became a leading candidate for harboring life within the Solar System. In his 1944 paper, Kuiper wrote that the spectrometry from his telescopic observations suggested that Titan was orange (8th paragraph). So there was an expectation of "oranginess" when the twin Voyager spacecraft flew past in 1981. The observations of Voyager allowed scientists to determine 1) the depth of Titan's atmosphere; and related to that 2) Titan was slightly smaller than Ganymede, because Titan's atmospheric depth had been underestimated; and 3) a temperature/pressure profile for Titan's atmosphere. Scientists determined that the temperature at the surface of Titan was a chilly 94 Kelvins (about -280 Fahrenheit). Well, so much for life on Titan. Life is based upon chemical processes and, in general, chemical processes proceed faster at higher temperatures. Not only was 94 Kelvins too low a temperature for life-sustaining processes as we know them, most chemicals (chiefly water) important to life as we know it are frozen at that temperature. So under the category of "potential abodes of life," Titan was relegated to the category of "also ran." Titan was referred to as similar to a "pre-biotic" (pre-life) Earth, or like the "Early Earth in a deep freeze." Even bolder claims were made that Titan may have its day as a habitable abode in a few billion years when our Sun swells to become a red giant.

Enter Cassini/Huygens. Since arriving at the Saturn system in July 2004, the Cassini and Huygens spacecraft have been imaging, sniffing

, and landing on

Titan, rewriting the textbook on this moon in the process (and I did a podcast

on this very subject for "365 Days of Astronomy

" last November 12th). In fact, this past June 21st, Cassini had its closest flyby of the moon Titan

that it will have during the entire mission. Now it turns out that computer simulations based upon Cassini observations, simulations which hint at depletions of various chemical species at Titan's surface may again hint at the possibility of life on Titan

. The results are very preliminary, but fascinating nevertheless. In the past six years we've still learned enough about Titan not to rule out the presence of life. In addition to that subsurface ocean previously mentioned, there appears to be cryovolcanism on Titan's surface

-- in one instance Cassini may have imaged an actual eruption

. If Titan's surface rocks are composed of ice, and magma is melted rock, and hydrocarbons like ethane and methane are common on Titan, then it's not too big of a stretch to imagine that magma chambers in Titan's subsurface could be life-sustaining cauldrons of hydrocarbon-laced water

. Microbes surviving in a magma chamber on a moon of Saturn is a concept that would have been the purview of science fiction only a few years ago, now it's a real consideration. Life on Titan? I guarantee that we've not heard the last on this subject.