This article appeared in Discover’s annual state of science issue as “The Supernova That Wasn't” Support our science journalism by becoming a subscriber.

For a while in 2020, the constellation Orion the Hunter looked like it was about to get a supernova shot in the arm. In January, Betelgeuse, one of the brightest stars in our sky — which forms Orion’s right shoulder — dimmed to levels unseen since modern observations began 150 years ago. Speculation about an imminent supernova followed the star’s every twinkle.

The Milky Way hasn’t had a supernova that’s visible from Earth since 1604, just a few years before Galileo turned his first telescope to the heavens. But was there really cause for all the excitement earlier this year?

Apparently not: In April, the dying red supergiant star let skygazers down by returning to its former glory.

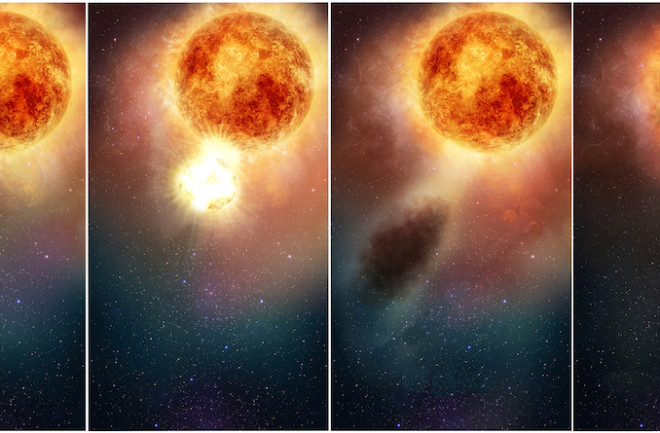

Meanwhile, all the attention meant observatories were keeping a close eye. According to a study published in The Astrophysical Journal, as Betelgeuse began to dim in late 2019, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope spotted hot, dense gas spewing through the star’s atmosphere at 200,000 mph.

Then, the following month, ground-based telescopes noticed something blocking the light from the star’s southern half. So, as the gas cooled, it could’ve created the dark cloud that blocked the starlight. Astronomers called it a stellar “sneeze.”

However, as Betelgeuse and Orion slipped into Earth’s daytime sky for the summer, they hid another surprise. A NASA sun-orbiting telescope called STEREO caught Betelgeuse dimming again between May and August, when it wasn’t visible from Earth. The variable star usually cycles from dim to bright over some 420 days, so astronomers say there’s still more to the mystery.

There’s little chance Betelgeuse will explode soon — and we’d likely get an advanced warning from neutrinos and gravitational waves if it did, astronomers say — but simulations suggest the sight would be awesome. The star is too far away to endanger Earth, but its supernova would shine in our daytime sky for up to a year and be bright at night for several times longer.

“Imagine a good fraction of the world staying up and staring at Betelgeuse, waiting for the light show to start, and a cheer going up around the planet when it does,” says astronomer Andy Howell of Las Cumbres Observatory in California.