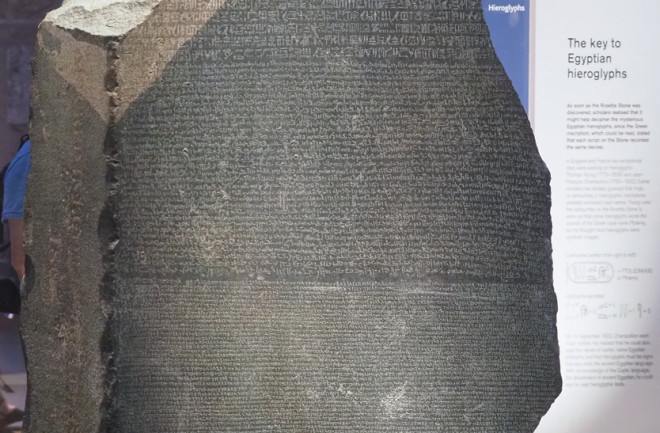

In 1799, a French soldier found and seized a precious stone tablet during Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt. Taken from a fort near the town of Rosetta, this inscribed slab, now widely known as the Rosetta Stone, became pivotal in deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. It is typically recognized as one of the most important finds in Egyptology.

On the Stone, the same message was written in three scripts, which enabled scholars such as Thomas Young and Jean-Francois Champollion to interpret hieroglyphs. As important as the Stone is, however, the text itself recounts a rather dull affair and is one of many copies made. It amounts to a decree by a council of priests from Memphis, Egypt praising the deeds of Ptolemy V Epiphanes who ruled Egypt at the time it was written.

Yet, the ancient Egyptians were not the only ones to draw up their decrees in multiple languages. Other peoples and civilizations followed similar customs, leaving steles, inscriptions and other artifacts that have puzzled archaeologists. Below are the stories of several other Rosetta-like stones that, in their own way, advanced knowledge of ancient and historical peoples and their languages.

Decree of Canopus

Like the Rosetta Stone, the Decree of Canopus is written in Egyptian hieroglyphs, Ancient Greek and Demotic scripts. Reclaimed in 1866 by German savants in Tanis, the artefact dates back to 238 B.C. It records a meeting of priests who praise Ptolemy III Euergetes, the ruler of Egypt at the time, and his wife Berenice, while setting up a cult in their deceased daughter’s honor. Other copies were found across different locations in Egypt. Aside from the fascinating events described, the Decree is lauded as another integral piece of the puzzle in understanding Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Behistun Inscription

The Behistun Inscription – also known as the Bīsitūn Inscription – records the exploits of King Darius of Persia in cuneiform in Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian. Dating back to around 520 B.C., the inscription was carved into a cliff face on Mount Bīsitūn in Western Iran. It also features a large relief showing Darius in all his splendor, looming over his conquered enemies. Within the text, Darius praises the ancient Iranian god Ahuramazda whom he claims helped him defeat Gaumâta, a certain usurper who attempted to claim his throne. It recounts his many exploits and victories: “After I became king, I fought nineteen battles in a single year and by the grace of Ahuramazda I overthrew nine kings and I made them captive,” it reads. This inscription played a key role in deciphering cuneiform writing.

The Nubayrah Stele

The Nubayrah Stele is literally another Rosetta Stone carved in limestone. Copies of this decree were distributed across Egypt, carrying word of Ptolemy V Epiphanes’ coronation to various settlements. Thus, this discovery, made in the 1880s, was not particularly surprising and another partial copy was found at the Temple of Philae. Though the far more famous Rosetta Stone was translated prior to these discoveries, these additional copies helped archaeologists and other researchers to fill out the missing pieces in the text.

Taposiris Magna Stele

Dubbed “another Rosetta Stone,” the Taposiris Magna Stele was discovered by archaeologists in the town of Taposiris Magna near Alexandria. Dated two years earlier than the Rosetta Stone, the limestone decree tells how Ptolemy V gave part of Nubia to the Egyptian goddess Isis. Unlike the Rosetta Stone, however, only Egyptian hieroglyphs and Demotic script survive on this sample.

Pygri tablets

In 1964, three gold tablets dating back to 510 B.C. were discovered in Pygri, Italy. Two were inscribed in Etruscan and one in Phoenician, a written language hailing from the eastern Mediterranean. At first, the tablets were heralded as a possible key to the Etruscan language. Though, it soon became evident that all three inscriptions describe the same event, they are written to different audiences and not exact translations of one another. The text dedicates a temple – known as ‘Temple B’ – to Uni, an Etruscan goddess. Her equivalent to the Phoenicians was Astarte, a goddess associated with love, fertility, war and hunting. The dedication was made by one Thefarie Velianas, who ruled as tyrant of the nearby city of Caere. Despite this, the tablets proved significant in understanding Etruscan and indicated that these two ancient peoples had developed close ties.

Karatepe bilingual

The Karatepe bilingual inscription proved pivotal for the study of Luwian hieroglyphs, a written language scribed by people in ancient Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). Written in Luwian and Phoenician, the text recounts the lives of the Kings of Adana. It was mistakenly understood as a language of the Hittites, who ruled over much of Bronze Age Anatolia. The text was originally written in Phoenician and translated to Luwian and was discovered in an ancient Hittite fortress by archaeologists in 1946. It was key to deciphering Luwian hieroglyphs.

Cippi of Melqart

Understanding the Pygri tablets and Karatepe bilingual was only possible by deciphering the Phoenician language. To this achievement, thanks is owed to the Cippi of Melqart, stone pedestals discovered on the island of Malta in 1694, written in both Greek and Phoenician. They carry a dedication to the Punic god Melqart, who was the top god of the city of Tyre. In Ancient Greece, Melqart became closely associated with the legendary hero Hercules. These dedications helped archaeologists unlock the Phoenician written language.

Myazedi inscription

Written in Pyu, Pāli, Old Mon, and Mranma, the Myazedi inscription dates from A.D. 1113. It tells how one King Kyanzittha made peace with his son, Prince Yazakumar, on his deathbed after a period of warfare between the Pagan and Mon kingdoms. The four languages were carved in stone on different faces of a pillar at the Myazedi pagoda in Myanmar. Though the texts are not identical translations of one another, it helped to partially decipher Pyu, an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was mainly spoken in modern-day Myanmar.