Long before Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin famously set foot on the moon, the hero of America’s human spaceflight program was a chimpanzee named Ham. On Jan. 31, 1961 — a few months before Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s pioneering flight — Ham became the first hominid in space.

Other nonhominid animals had ventured into space before Ham, but he and his fellow “astrochimps” were trained to pull levers and prove it was physically possible to pilot the Project Mercury spacecraft. And, unlike many other unfortunate primates in the spaceflight program, Ham survived his mission and went on to have a long life.

“Ham proved that mankind could live and work in space,” reads his grave marker in New Mexico.

Pioneering Primates

The U.S. Air Force was the first to launch primates into space. Instead of chimps, smaller monkeys were their preferred choice. But those early missions didn’t go well — for either human or animal.

In 1948, a decade before the creation of NASA, the Air Force strapped a male rhesus monkey named Albert into a capsule on top of a souped-up, Nazi-designed V-2 rocket and launched it from White Sands, New Mexico. Poor Albert suffocated before he reached space.

The next year, a monkey named Albert II was sent on a similar mission. Unlike his predecessor, Albert II succeeded in becoming the first monkey to survive a launch and reach space. Unfortunately, on his journey home, Albert II died when the capsule’s parachute failed. His spacecraft left a 10-foot-wide crater in the New Mexico desert.

In 1951, the Air Force finally managed to keep a monkey — this one named Albert VI — alive through both launch and landing. But his capsule failed to reach the boundary of space, leaving him out of the record books.

The honor of first primates to survive a return trip to space goes to a squirrel monkey named Miss Baker, and a rhesus macaque named Able. The pair were launched in 1959 on a Jupiter rocket, an intermediate-range ballistic missile designed to carry nuclear warheads, not monkeys. Sadly, Able died just days after returning to Earth due to complications from a medical procedure.

While America was struggling to send monkeys into space, their adversaries were racking up animal success stories. Rather than monkeys, the Soviet Union preferred to crew their early spacecraft with stray dogs. And by the time of Miss Baker’s and Able’s trip, the country had already safely launched and landed dozens of canines. (Though they also experienced a number of gruesome dog deaths.)

NASA’s Astronaut Chimps

By the early 1960s, the U.S. was ready for its first real human spaceflight program, Project Mercury. But instead of monkeys — or humans — the nascent National Aeronautics and Space Administration decided its inaugural class of astronauts would be chimps.

Monkeys, chimps and humans are all primates. However, chimpanzees and humans are both hominids, which means we’re much more closely related. In fact, humans share more DNA with chimps than with any other animal.

Beyond their genetic similarities to humans, chimps are also incredibly smart and have complex emotions. This is why NASA figured that if chimps could endure the trip beyond Earth’s atmosphere in primitive early space capsules, there was a good chance a human astronaut could survive the journey, too. And, whereas monkeys and dogs had been mere passengers, NASA needed a test subject with the intelligence and dexterity to actually prove it could operate a spacecraft.

As NASA put it: “Intelligent and normally docile, the chimpanzee is a primate of sufficient size and sapience to provide a reasonable facsimile of human behavior.”

Ham Joins Mercury

All told, the U.S. government acquired 40 chimps for its Mercury program. And one of those males was Ham. He had been captured by trappers in the French Cameroons and taken to the Miami Rare Bird Farm in Florida. From there, Ham and others were soon sold to the military and transferred to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.

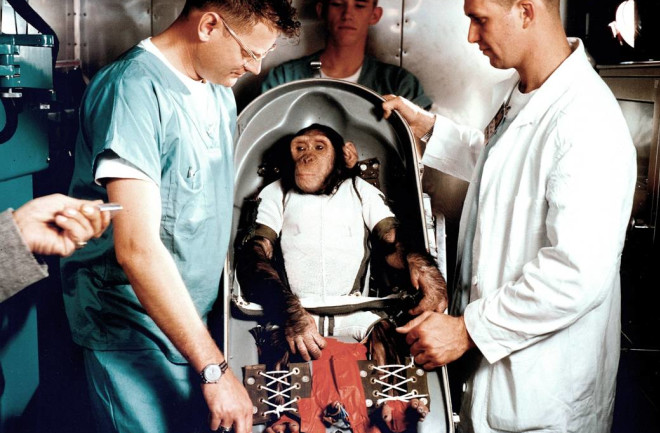

The chimps received daily training, including some of the same G-force exposure simulations as their human Mercury 7 counterparts. But, most importantly, handlers taught Ham and the other chimps to pull a lever every time a blue light came on. If they performed the task, they got a tiny banana treat. If they failed, they got a small electric shock to their feet.

Over the course of the training, handlers winnowed the final group of astrochimps down to just six, including four females and two males. Then, with their training complete, the Air Force sent the hominids to Cape Canaveral in Florida on Jan. 2, 1961.

Out of the six chimps, NASA and an Air Force veterinarian ultimately selected Ham, then known as No. 65. He was chosen just before his flight because he seemed “particularly feisty and in good humor,” according to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Ham’s Successful Spaceflight

Those traits would pay off during the mission. Following his launch on Jan. 31, 1961, Ham’s Mercury capsule unintentionally carried him far higher and faster than NASA intended. His capsule also partially lost air pressure, though the chimp was unharmed because he was sealed inside an inner chamber.

We’ll never know what Ham was thinking during his six and a half minutes of weightlessness. But, like the later human Mercury astronauts, Ham could have seen out of the capsule’s small porthole window.

As far as his mission was concerned, Ham successfully pulled his lever at the proper time, performing only a tad slower than he had during practice runs on Earth. By simply tugging on a lever, Ham proved that human astronauts could perform basic physical tasks in orbit, too.

Roughly 16 and a half minutes after launch, Ham splashed down in the ocean. And although the capsule took on some water while recovery crews converged, the chimp seemed unfazed once aboard the rescue ship USS Donner — even shaking the commander’s hand. Ham eventually became the subject of documentaries and cartoons and graced the covers of national magazines.

He lived out the rest of his life in the North Carolina Zoo, where he died in 1983 at age 25.

Following Ham, just one other chimp would ever journey to space. Enos, who was also bought from the Miami Rare Bird Farm and trained alongside Ham, orbited Earth on Nov. 29, 1961. He was the third hominid to circle our planet, following cosmonauts Gagarin and Gherman Titov.

In the decades since, many other types of monkeys have flown to space on U.S., Russian, Chinese, French and Iranian spacecraft. NASA continued sending monkeys to orbit all the way into the 1990s, when pressure from animal rights groups, including PETA, pushed the space agency to reexamine the ethics of such research. As a result, NASA pulled out of the Bion program, a series of joint missions with Russia that was intended to study the impact of spaceflight on living organisms.

“These animals performed a service to their respective countries that no human could or would have performed,” says NASA’s history of animals in spaceflight webpage. “They gave their lives and/or their service in the name of technological advancement, paving the way for humanity’s many forays into space.”