Sharks and seals weren’t always the top predators of the oceans. Approximately 518 million years ago, that title went to none other than worms.

According to a new study in Science Advances, a team of researchers recently found the fossils of a previously unknown worm from around 518 million years ago. Terrorizing the oceans around northern Greenland, these fossils were some of the Cambrian’s fiercest, free-swimming predators, representing a long-lost arrow worm, forgotten with the passage of time.

Read More: The "First Predators" Ruled a World Full of Bacteria

Past Predators Face Off: The Arthropods and Arrow Worms

It was previously thought that primitive arthropods — animals from the 529-million-to-521-million-year-old Arthropoda phylum — were the dominant predators of Early Cambrian oceans. But the new study suggests that the primitive arrow worms, or chaetognaths, from the 538-million-year-old Chaetognatha phylum took that distinction instead, being bigger and deadlier at the time than previously believed.

What Were the Timorebestia?

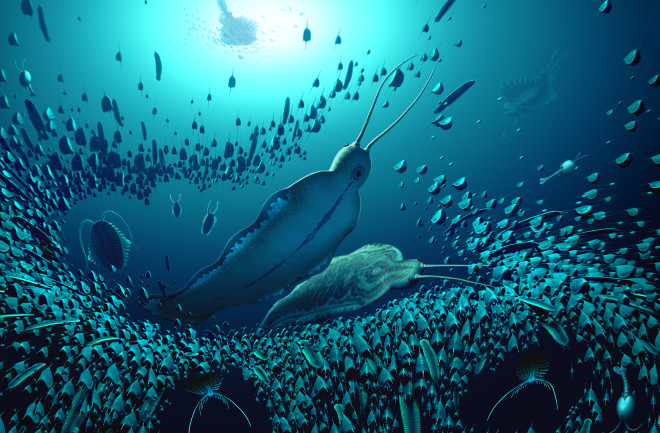

Labeled Timorebestia, or “terror beasts” in Latin, the newly found fossils have strange, short heads and substantial antennae. Fitted with massive, munching jaws on the inside of their mouths, the 13 fossil arrow worms analyzed in the study also feature long, lateral fins — a perfect fit for swimming through the open ocean. Including their antennae, the specimens stretched to lengths of over 11 inches, clinching their position among the top predators of the period.

“Timorebestia were giants of their day and would have been close to the top of the food chain,” said Jakob Vinther, a senior author of the study and a paleontologist from the University of Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences and School of Biological Sciences, according to a press release. “That makes it equivalent in importance to some of the top carnivores in modern oceans, such as sharks and seals, back in the Cambrian period.”

Why Were the Timorebestia Important?

According to the researchers, the study suggests that the oceans of the Early Cambrian were more diverse — and more deadly — than once thought. “Our research shows that these ancient ocean ecosystems were fairly complex, with a food chain that allowed for several tiers of predators,” Vinther said in a press release.

Read More: This Predatory Jellyfish Lived Before Plants Had Even Evolved

Timorebestia: A Taste for Ancient Arthropods

Found in the sediment of the Sirius Passet Lagerstätt fossil locality of northern Greenland, the specimens were so well-preserved that the researchers could identify the contents of their digestive systems. Inside their stomachs, they found an assortment of Isoxys — a small, swimming arthropod from the Cambrian period.

“We can see these arthropods [were] a food source [for] many other animals,” said Morten Lunde Nielsen, another author of the study and a former student at the University of Bristol, in a press release. “They are very common at Sirius Passet and had long protective spines, pointing both forwards and backwards. However, they clearly didn’t completely succeed in avoiding that fate [of predation], because Timorebestia munched on them in great quantities.”

Arrow Worms, Past and Present

According to the researchers, modern arrow worms are smaller predators that survive on meals of tiny zooplankton. “Today, arrow worms have menacing bristles on the outside of their heads for catching prey, whereas Timorebestia has jaws inside its head,” said Luke Parry, another author of the study and a palaeobiologist at Oxford University, in a press release. “This is what we see in microscopic jaw worms today — organisms that arrow worms shared an ancestor with over half a billion years ago.”

Because of those similarities, the researchers stress that Timorebestia imparts new insights into the transformations of worms over time. “Timorebestia and other fossils like it provide links between closely related organisms that today look very different,” Parry said in the press release.

In other words, the fossils allow researchers to trace the path that arrow worms followed throughout millions and millions of years, moving from terrifying, top predators to the petite, plankton-munching worms that swim the oceans today.

“We are very excited to have discovered such unique predators in Sirius Passet,” said Tae Yoon Park, another senior author of the study, from the Korean Polar Research Institute. “Our discovery firms up how arrow worms evolved.”

Read More: The Most Fearsome Ocean Predator Is This Superhero Shrimp