At the center of the Milky Way is a supermassive black hole, and ringing it are ultramassive young stars that should not be there: They exist under gravitational conditions that shouldn’t permit the process of star formation. In August Ian Bonnell and Ken Rice, a pair of Scottish theorists, published a model that might account for these oddballs.

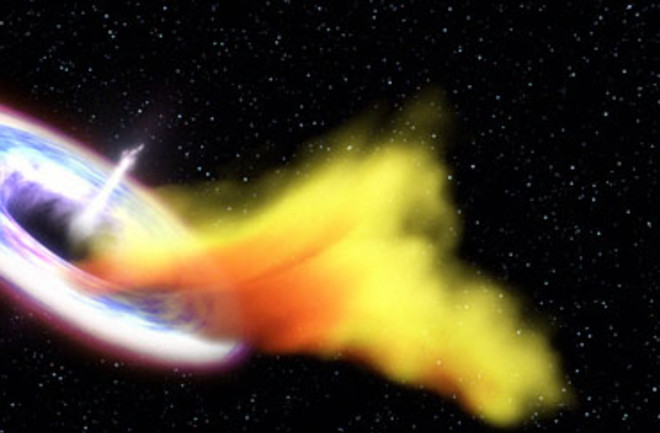

Using a computer simulation of our galaxy’s core, Bonnell and Rice sent a virtual interstellar gas cloud, such as might result from a collision of other, smaller clouds elsewhere, plunging toward an immense black hole. Gravitational forces ripped the cloud apart, creating an unstable disk around the black hole. Within this fragmenting disk, compression spurred on by the black hole appeared to generate temperatures high enough to sustain the formation of very massive stars. These new stars remained bound in orbit to the black hole but remained far enough away to avoid being absorbed.

Bonnell, an astrophysicist at the University of St. Andrews, says he can imagine only one other extreme star-making setting that could produce so many stellar behemoths: the hot, dense universe just after the Big Bang. “But we can’t see those stars,” he says. “They are long gone.”