This story was originally published in our January/February 2022 issue. Click here to subscribe to read more stories like this one.

In late 2017, paleontologist Qiang Ji showed his anthropologist colleague Xijun Ni photos of a human skull with a hefty browridge. Besides missing all but one tooth, the cranium appeared remarkably intact — making it one of the best-preserved skulls from any human ancestor or relative. “I was shocked,” recalls Ni. “I said, ‘This is the most important discovery, [more] than any of your dinosaurs.’ ”

Ji, a dinosaur expert at Hebei GEO University in China, didn’t excavate the specimen. It reportedly surfaced in 1933, when a contractor was building a bridge near Harbin City in northeast China. After encountering the fossil, he stashed it in a well to protect it from Japanese occupiers. The noggin remained there for 85 years, until the dying man divulged its location. His grandchildren retrieved the skull and, with Ji’s persuasion, donated it to the Geoscience Museum of Hebei GEO University.

Over the next three years, Ni and collaborator Chris Stringer tried to decipher the fossil. Normally they’d date it via geologic materials from its burial spot, but that precise location was unclear. So the scientists performed chemical analysis of powder drilled from the fossil, along with sediment lodged in the nasal cavity. By comparing these values to sediments and fossils collected near the bridge, they dated it between 309,000 and 146,000 years old.

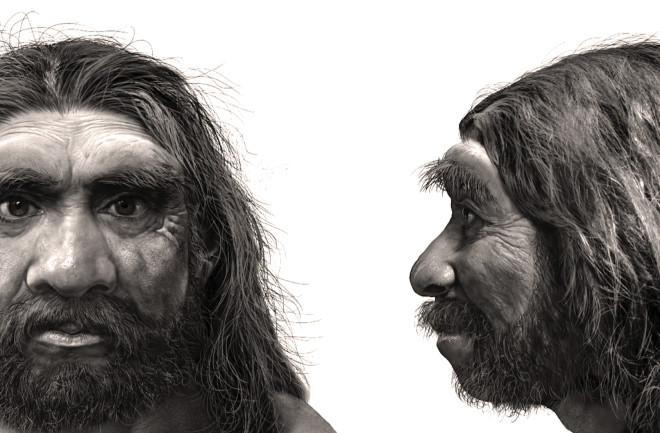

In that era, several varieties of humans inhabited Earth, including Neanderthals, Denisovans and Homo sapiens. The Harbin skull’s browridge looked Neanderthal-ish, yet traits like the flat cheekbones resembled sapiens. The scientists calculated its similarity to 95 other fossils and contrasted physical traits like the remaining molar tooth’s dimensions. The skull most closely matched eight specimens, including several discovered in China since the 1900s — which may come from a sister species of H. sapiens that’s closer in relation to us than Neanderthals. The mystery skull now belongs to a previously unnamed species called Homo longi, or Dragon Man, after a Harbin river.

The team, which included scientists at the Australian National University and the London Natural History Museum, detailed their findings in three June papers in The Innovation. Since then, anthropologists have buzzed over another possibility: Dragon Man may be Denisovan, a name given to ancient DNA previously extracted from isolated teeth and bone bits. These measly fossils leave the Denisovan’s physical appearance an enigma.

Ni finds the Denisovan hypothesis reasonable, but hardly proven. Now, his team is searching the Harbin region for other fossils, CT scanning the skull’s interior, and trying to extract DNA and proteins. Dragon Man may belong to a sister species of sapiens, the veiled Denisovans — or an entirely new type of human.