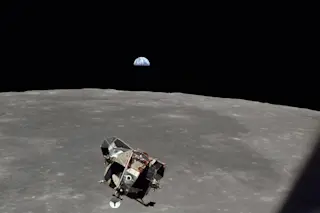

One of NASA’s original justifications for building a space station was to perform microgravity research, which would look into ways to manufacture new materials in the weightlessness of space. Efforts to drum up commercial interest failed, apparently because corporate America does not believe the work will pay off enough to warrant the investment. Similar efforts in Japan, however, produced a much different result.

Construction begins this year on a 68-foot, 28.5-ton section of the space station devoted almost exclusively to microgravity research. The Japanese Experiment Module will include a pressurized work space for astronauts; a platform exposed to the vacuum of space, where many of the experiments will take place; and a robotic arm for retrieving the experiments into an air lock when they need tending. Total cost: $3 billion.

The payoff is the potential to create new materials. Oil and water don’t mix on Earth because oil, being less ...