The idea of shrinking things down to a more convenient size seems so enticing. It’s a superpower for Ant-Man, kicks off the adventures in Honey I Shrunk the Kids, and, of course, the Simpsons had fun with the idea too. (Shrinkage has come up in other contexts, as well.)

Now, in real life, a team of MIT and Harvard scientists has gotten in on the fun by devising a new way of constructing nanomaterials — tiny machines or structures on the order of just a billionth of a meter. They call it Implosion Fabrication (ImpFab) and they do it by building the materials they want and then literally shrinking them down to the nanoscale. The findings appear today in the journal Science, and may pave the way for next-gen materials, sensors and devices.

3D Nanoprinting

Researchers have already been exploiting the nanoworld, of course, but the current methods of “nanofabrication” weren’t ideal. They often require building things layer by layer, or necessitate the product to be self-supporting, which limits the creations to fairly simple shapes, using only a narrow range of materials.

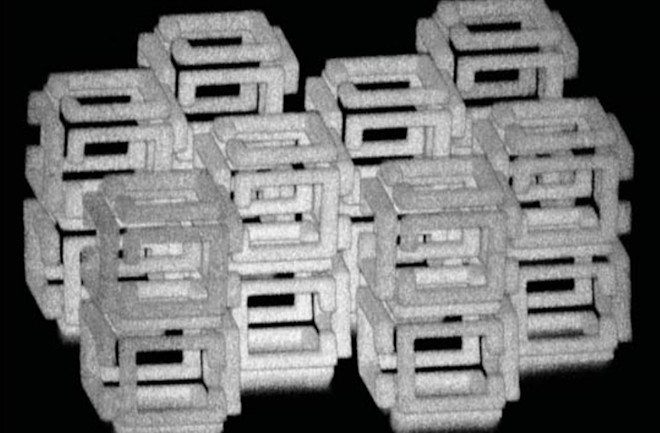

The ImpFab process gets around all that. As the authors write, “We present a strategy for the direct assembly of 3D nanomaterials consisting of metals, semiconductors, and biomolecules arranged in virtually any 3D geometry.” Almost any design they (or anyone else) can think of is now achievable within the nanoscale — even ones with “discontinuous” patterns, i.e., they don’t all touch each other.

“We fabricated a non-layered, non-connected 3D structure comprised of many 2D substructures arranged at different angles relative to each other in space, which would not lend itself to fabrication by other means,” they add, somewhat boastfully.

That Shrinking Feeling

It’s all possible thanks to that shrinking process. The team first creates a pattern within a special “polyacrylate/polyacrylamide hydrogel” — a scaffolding upon which the particles of the desired material itself would then hang. That’s how they could create, in three dimensions, the exact kind of shapes and structures they wanted, without worrying about how the thing would hold itself up.

Once it was built, the final step was the actual shrinking, by as much as 10-20 times. The gel was specially chosen because of how bloated with water it could become, allowing it to constrict — shrink — when treated chemically and dehydrated. The materials constructed within it shrank right along with the gel, without losing their structural or even electrical properties. (The shrinking wasn’t always even, but the team could correct for that; to prove their mastery over the process, they built a rectangular block and shrunk it down to form a perfect cube.)

So now, engineers have a new way to create subtle and tiny electrical and mechanical devices, but as a bonus, scientists also have a new method of probing the material world, allowing them to learn more about the physical properties of various materials. Plus, the authors say the modular nature of the ImpFab process means variations on its themes — different chemical methods of shrinkage, perhaps, or novel construction materials — could yield even more new ways of putting stuff together. Let’s see Ant-Man do that!