Righting the wrecked Costa Concordia involved more than 500 people from 26 countries. | Va lerio Nicolosi/Demotix/CORBIS

In September, modern technology applied to a centuries-old technique raised the wreck of the luxury liner Costa Concordia in an unprecedented engineering feat.

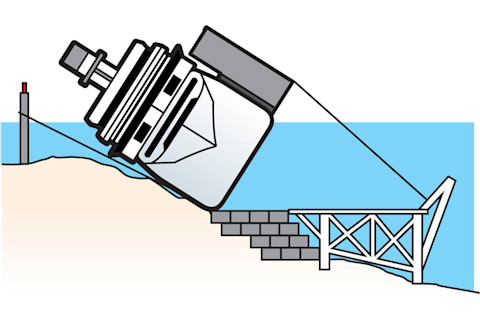

The massive cruise ship ran aground in a marine reserve off Italy’s Giglio Island in January 2012, killing 32. It settled on its starboard side on two undersea rock ledges. Salvage experts turned to parbuckling — using a sling to right a vessel on an inclined plane. The technique dates to the 17th century and has been used on other modern ships: The USS Oklahoma was parbuckled after sinking at Pearl Harbor. But never have engineers attempted it on this scale.

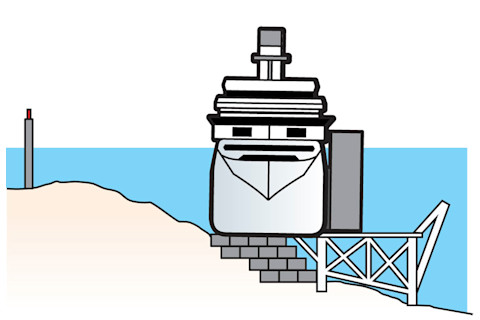

Chains from port side sponsons to shoreline act as slings. | Jay Smith/Discover

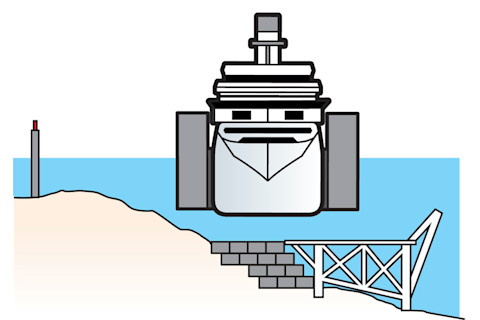

The righted ship is stabilized on platform and cement bags. | Jay Smith/Discover

Starboard sponsons are added to distribute buoyancy. | Jay Smith/Discover

Size matters: To right the Concordia — more than twice the size of the Titanic — engineers built platforms, which together were longer than a football field, supported by 21 5-foot-diameter pillars sunk 30 feet into the granite seabed. Bags filled with more than 16,000 tons of eco-friendly cement were placed between the hull, ledges and platform to support the ship’s bulk once it was rolled off its side.

Heavy metal: The operation required 56 chains weighing almost 3 million pounds in total. To right the ship, computer-controlled hydraulic jacks in shoreline turrets slowly pulled 22 chains that ran from the port side under the hull to the shore.

Float your boat: Hollow metal boxes called sponsons — some as tall as 11 stories and weighing more than 500 tons — were welded to the exposed port side. Once the ship was righted and resting on the platforms, more sponsons were welded to the starboard side, making the ship buoyant enough to be towed.

The cost of Costa salvage: $800 million and counting.

Cleanup on Isle Giglio: The wreck’s environmental impact has been limited, with minimal leakage of fuels and waste materials. Post-towing cleanup operations should restore the seabed to its natural state.

Post-parbuckling, the righted Costa Concordia awaits final decision on where it will be towed and scrapped in mid-2014. | Eidon Photographers/Demotix/CORBIS

[This article originally appeared in print as "The Mother of All Parbuckles."]