Voting machines are one of the few areas where technology has decidedly taken us a step backward. The electronic voting machines that one-third of American voters will be using in November are no more reliable than your home computer.

Direct-recording electronic voting machines are incredibly easy to hack; Princeton University security expert Ed Felten proved it by accessing a Diebold machine’s memory card with a hotel minibar key he bought online. In less than one minute, Felten was able to install undetectable vote-stealing software. Then there is the garden-variety computer error. Touch-screen machines in Sarasota, Florida, recorded an 18,000-vote undercount in a congressional race decided by fewer than 400 votes. Paper itself was never foolproof (remember those chads?), but a stolen, lost, or stuffed ballot box risks mere hundreds of votes while a hidden computer glitch risks millions. And since viruses can spread, one machine’s infection can quickly cross county lines.

Unfortunately, our current digital democracy leaves massive fraud and massive error imperceptible and untrackable. And transparency—not just of the software code, but of the whole voting system—has never been more important. Each voter should be able to verify that his or her own vote has been counted correctly from the booth all the way to the final tally. But how can you lay bare the secret ballot without sacrificing the privacy that makes democracy work?

Computer scientists led by crypto grapher David Chaum claim to have the solution. Their latest scheme, called Scantegrity II, would make elections both transparent (to catch error or vote-alteration fraud) and private (to prevent coercion, intimidation, and vote buying). They presented Scantegrity II (the “II” stands for “invisible ink”) at the USENIX/ACCURATE Electronic Voting Technology Workshop in July and plan to test it in a municipal election in 2009. Here's a step-by-step guide to how it works:

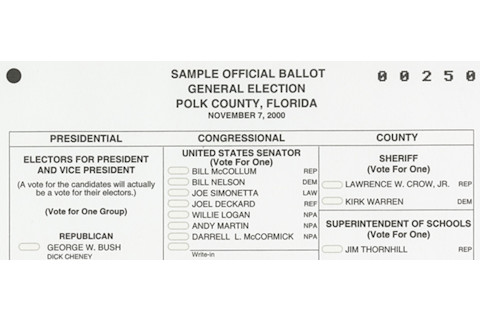

As you walk into the voting booth, a poll worker hands you a regular pen, a special decoder pen (no, really), and a ballot that looks like this:

The ballot contains a unique serial number that's printed on both the upper-right corner and the receipt at the bottom of the page that you tear off and keep.

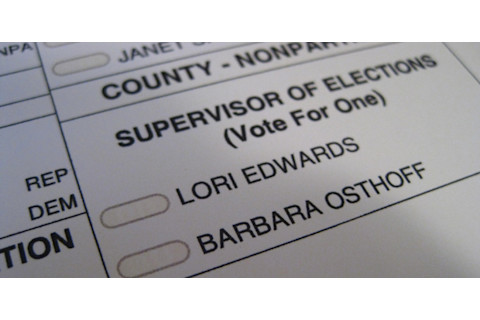

The ballot is divided into separate boxes for each political race, and each candidate has a blank bubble next to his or her name:

Image courtesy of Aleks Essex | NULL

To vote, you mark the circle next to your chosen candidates with the decoder pen. A two-or three-letter code will "magically" appear in each bubble you mark, like so:

The ballot's serial numbers, as well as the invisible codes, have all been created and recorded by voting officials before the election to eliminate the possibility of ballot-box stuffing. If any would-be fraudsters tried to create and fill out fake ballots, they could easily be thwarted: Even if they were able to replicate real serial numbers, there's virtually no way the forged ballots' invisible codes would match those on the real ballots.

If you decide that you want to check and make sure your vote was counted correctly, you can write each of the now-visible codes on your receipt, which you detach from the ballot and take with you. The rest of the ballot you hand to election officials, who immediately scan it with an optical scanner, recording your vote in a database.

Once you leave the polls, you can access a designated election website and log in to a public database. Then you enter your ballot serial number and a list of your invisible ink codes appears on the screen. (Only the "secret" codes will be in the database, not the names of the candidates themselves—that way, hackers can't see who you voted for, so your vote remains private, and no one can change your vote online.) If the codes in the database match the codes you wrote down, your vote was indeed counted correctly.

And if you don't want to go to the trouble of hitting the Internet after you vote, don't worry: You can trust that enough other people—including bloggers, political staff members, and just about anyone in the main stream media—will. And they should be enough, according to Chaum and his team: If only one or two percent of voters check their receipts, it will create a 95 percent chance that no fraud occurred. Just imagine if all of us got into the act.