Wind power has long been touted as a major energy resource, but for decades no one knew how much energy it could actually yield. Then three years ago Stanford University atmospheric scientists Cristina Archer and Mark Jacobson did a detailed calculation based on known patterns of air motion. Using a conservative approach, they counted only the energy that could be generated from winds blowing over land at an altitude of 80 meters, the approximate height of a typical modern wind turbine. Under perfect conditions, the total would be 72 trillion watts.

It is a handsome quantity. In 2007 the entire electrical generating capacity of the United States was just a bit more than 1 trillion watts. But Archer realized that this number barely hints at the potential. Wind speed rises with altitude, and available power rises at the cube of wind speed. This means that 72 trillion watts is a lowball estimate. A few miles up, a turbine blade could generate up to 250 times the energy of the same blade near the ground. The prospect, Archer says, “is just super-incredibly exciting.”

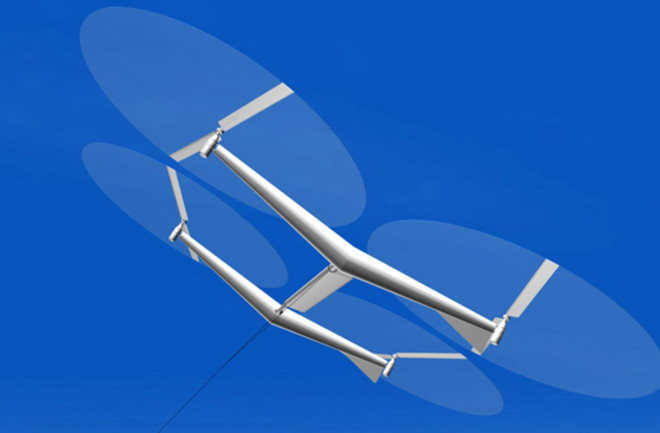

One scheme for harvesting that breezy bounty comes from Bryan Roberts, an engineering professor at the University of Technology in Sydney, Australia, and Sky WindPower, the San Diego–based company developing his work. The team is designing kites with rotors that fly helicopter-style to altitudes of a mile or more, where the winds are strongest. Upon arrival, the rotors switch to generating mode, sending current down their tethers, which might be many miles long. When the winds shift, the platoon of kites (called flying electric generators, or FEGs) simply pursue them. Other teams are working on related approaches.

Of course, as different kinds of wind-power kites come online, there may be challenges: Will thunderstorms interfere? Will a fleet of kites tangle up? These questions have apparently stymied the federal government, which thus far has invested nothing.

Some place the blame on image. Fusion, with much grander problems and bigger unknowns, attracts several hundred million bucks a year. It can’t help that the basic unit here—a kite on a string—is so totally unlike anything in the current energy infrastructure. The cosmetics are wrong.

One possible alternative: small, ultracheap, low-altitude energy kites, such as those being built at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) in Massachusetts. Such scaled-down models are intended for niche applications off the grid—for instance, in developing nations. Unlike FEGs, which carry the generators into the sky and send current down the tether, the WPI kite would bob up and down just a few hundred feet in the air, creating jerks or pulses in the tether that would power a generator on the ground. The first models look like machines that could have come out of the 19th century, and you can actually see them work; that might make all the difference.

Click here to see the rest of DISCOVERmagazine.com's special energy coverage.