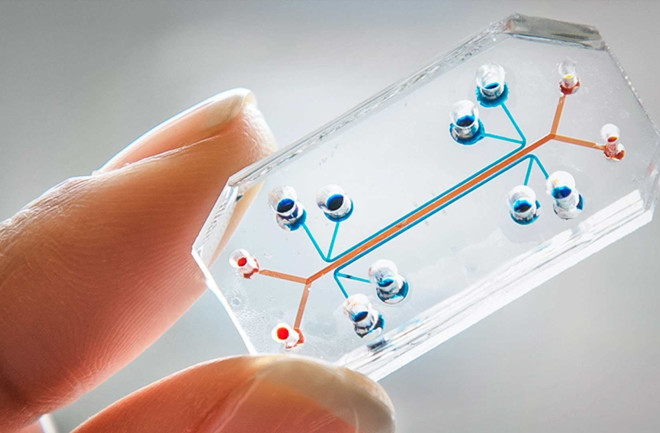

Scientists have long experimented with organs-on-chips: tiny representations of human organs, such as lungs, hearts and intestines, made from cells embedded on plastic about the size of a computer memory stick. Channels lined by living vascular cells then mimic the body’s circulatory system. But our bodies are complex systems of organs, so testing drugs on individual miniature organs only goes so far. Researchers now are aiming for something more: full-blown human bodies-on-chips.

The kick-start came from the U.S. Department of Defense, which wanted a quick and effective way to develop and test drugs and vaccines against biological and chemical weapons. So federal agencies funded various projects to develop chips representing all the major organ systems. Each organ-on-a-chip hosts real human tissue kept alive by a synthetic circulatory system. Join enough of them together, and you’ve got a high-tech stand-in for the human body.

Researchers at Harvard’s Wyss Institute have 12 different organ chips in development, representing everything from lungs to skin. They’re working to combine 10 of them that will operate as a system for at least four weeks in an instrument called the Interrogator (named after its ability to analyze, or interrogate, how they work together). Don Ingber, the institute’s director, says he and his colleagues already have succeeded in coupling two different pairs of chips — lung-liver and lung-heart — a key step toward the ultimate goal.

“These platforms are designed to be as close to human as you can get, but enable experimental manipulation,” says D. Lansing Taylor, director of the University of Pittsburgh Drug Discovery Institute. Taylor is growing miniature livers that will be used to help re-create the body’s main system for drug absorption and metabolism.

Human bodies-on-chips would have applications far beyond drug development. For instance, toxicologist Thomas Hartung of Johns Hopkins hopes that connecting his minibrains to other micro-organs will show how toxins affect neural development and how they’re processed in the body. Conducting such brain experiments on animals is expensive and time consuming — and on people, it’s impossible.

Enter the human bodies-on-chips.

Liver

Minilivers from Pittsburgh’s D. Lansing Taylor mimic a liver’s cell-generation and detoxification abilities. They’ll be part of a three-organoid connection that will link up minilivers, minikidneys and mini-intestines to re-create the body’s main system for processing drugs.

The Brain

Thomas Hartung of Johns Hopkins is growing miniature brains that contain the same kinds of cells (left) found in full-size brains. Hartung hopes to build a brain-on-a-chip that can eventually plug into the Interrogator.

Lung

The lung-on-a-chip was the first human organ to be scaled down to chip form. Ingber’s design, which should work with the Interrogator, re-creates the lung’s processes with living cells.

Kidney

Taylor’s minilivers also should combine with these miniature kidneys-on-chips, developed by scientists at the University of Washington.

Intestines

Fellow Johns Hopkins researcher Mark Donowitz, meanwhile,is working on the third part of the system, re-creating the functions of intestine cells (above). Researchers aim to combine every major organ system to create a true human body-on-a-chip stand-in.

Bone Marrow

Bone marrow-on-a-chip can successfully manufacture blood cells.

[This article originally appeared in print as "Pieces of Me."]