As neural networks become more powerful, algorithms have become capable of turning ordinary text into images, animations and even short videos. These algorithms have generated significant controversy. An AI-generated image recently won first prize in an annual art competition while the Getty Images stock photo library is currently taking legal action against the developers of an AI art algorithm that it believes was unlawfully trained using Getty’s images.

So the music equivalent of these systems shouldn’t come as much surprise. And yet the implications are extraordinary.

A group of researchers at Google have unveiled an AI system capable of turning ordinary text descriptions into rich, varied and relevant music. The company has showcased these capabilities using descriptions of famous artworks to generate music.

Music Datasets

A key factor in enabling text-to-image systems is the existence of large datasets of images with descriptions. These can then be used to train a neural network. However, similar annotated datasets do not exist for music.

But in 2022, Google Research unveiled an algorithm called MuLan that produces a text description of a piece of music. A good text description usually needs to cover the rhythm, melody, timbre and the various musical instruments and voices it might contain.

Now Christian Frank and colleagues at Google Research have used MuLan to generate descriptive captions of copyright-free music. Then then use this database to train another neural network to do the opposite task of turning a caption into a piece of music. They call the new algorithm MusicLM and show how it generates music based on any supplied text or can modify audio files of humming or whistling in a way that reflects a caption.

Evaluating such an algorithm is a difficult task because it requires a gold standard dataset of annotated music files, ideally created by humans. So Frank and co created one. They asked ten professional musicians to write text descriptions of 5500 ten-second clips of music.

Each description consists of about four sentences that describe the genre, mood, tempo, singer voices, instrumentation, dissonances, rhythm and so on. The team call this database MusicCap and have made it public so others can use it as a gold standard.

Frank and co then evaluate the music from MusicLM by looking at the audio quality and how well it sticks to the audio description.

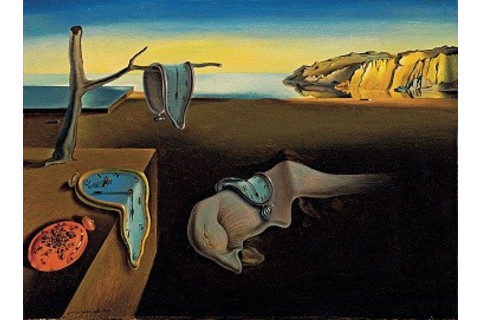

The results speak (or play) for themselves. To showcase the algorithm, Frank and co gave MusicLM text descriptions of several famous paintings and published the resulting music.

Here are a few of the results:

The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dalí (Source: Wikipedia)

The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dalí (click to listen)

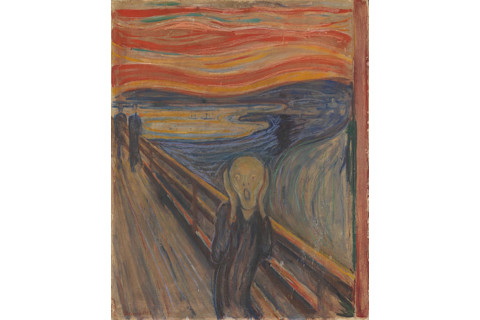

The Scream by Edvard Munch (Source: Wikipedia)

The Scream by Edvard Munch (click to listen)

The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh (Source Wikipedia)

The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh (click to listen)

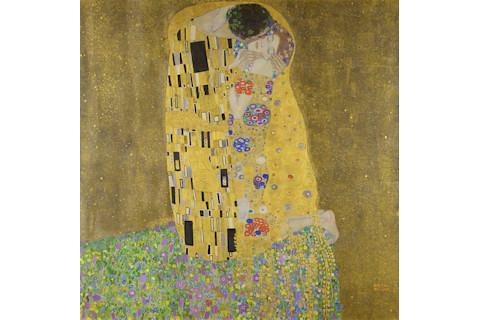

The Kiss by Gustav Klimt (Source: Wikipedia)

The Kiss by Gustav Klimt (click to listen)

The team has released other results here.

The algorithm isn’t perfect, of course. One significant problem is that the algorithm suffers from the same biases as the data used to train it. This raises questions “about appropriateness for music generation for cultures underrepresented in the training data, while at the same time also raising concerns about cultural appropriation,” say the researchers.

Then there is the issue of appropriation in general—reproducing creative work created by others. To avoid this issue, the team used open music datasets that are copyright free. But they also tested the output to see how closely it resembled input data. “We found that only a tiny fraction of examples was memorized exactly, while for 1% of the examples we could identify an approximate match,” say Frank and co.

Nevertheless, this is interesting work that should dramatically extend the AI toolsets available for creative workers. It’s not hard to imagine the AI system creating works such as short films, in which the script is written by an AI, turned into video by an AI with a soundtrack generated by an AI—all based on a relatively short text input from a human.

It’s inevitable that these outputs will eventually become hard to tell from real videos.

Google hasn’t made MusicLM publicly accessible. But it must surely be only a matter of time before somebody else creates a similarly capable AI that is publicly available.

How long before these films start winning awards at film festivals, start spreading on social media and become the targets of legal cases themselves?

Ref: MusicLM: Generating Music From Text: arxiv.org/abs/2301.11325