The thrill of a crime story is the unfolding of “whodunnit,” often against a backdrop of very little evidence. Positively identifying a suspect, even with a photo of her face, is challenging enough. But what if the only evidence available is a grainy image of a suspect’s hand?

Thanks to a group at the University of Dundee in the UK, that’s enough information to positively ID the perp.

The Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification (CAHID) can assess vein patterns, scars, nail beds, skin pigmentation and knuckle creases from images of hands to show, with high reliability, that police got the right person in several very serious court cases in the UK. CAHID specializes in human identification, and was also the group that famously reconstructed King Richard III’s face after his body was found in a car park in Leicester in 2012.

In the Dark

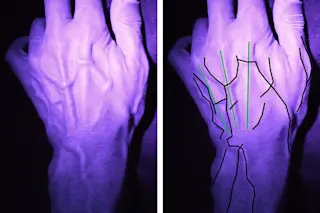

The technique was born in 2006 when local police came to the team with a Skype video recorded in the dark, which had been languishing on their desks for some time. The dark recording conditions meant that images were taken in infrared light, and just a shot of a hand and forearm were in view. That was enough for the team to match the superficial vein patterns in both the offender and suspect with high reliability.

“The infrared light interacts with the deoxygenated blood in the veins so you can see them as black lines,” says Professor Dame Sue Black, who led the research. “You are actually seeing the absorption of the infrared light into the deoxygenated blood.” Black is an expert in forensic anthropology who has been crucial in high-profile criminal cases in the UK and headed the British Forensic Team’s exhumation of mass graves in Kosovo in 1999.

Building a Research Basis

Since that first case in 2006, CAHID has used the method in roughly 30 or 40 cases per year, and the team has also applied this procedure to intelligence and counter terrorism work. They have been hard at work trying to establish an academic explanation for their method over the past decade.

“It is important that we are able to say with some degree of reliability that we can exclude a suspect, or say there is a strong likelihood this is the same individual,” says Black.

In order to develop their technique further, CAHID created a database of 500 police officers’ arms and hands, taken in both visible and infrared light.

“This gave us the most phenomenal database to start looking at the likelihood of different patterns of veins, areas of skin pigmentation,” says Black, “whether they be freckles, liver spots or birth marks. We looked at scars and patterns across the knuckles. All of these started to show us that there is a tremendous amount of individual variation, meaning we could use the images to identify whether it is or is not somebody who is being accused of a crime.”

Anatomical studies dating back to the 1500s have shown the high variability of vein patterns between individuals. Superficial vein patterns are said to come about during embryological development and nail bed morphology, and freckle patterns have genetic origins but are also influenced by environmental factors.

Getting to Work

CAHID’s images are not always the only evidence that the police have, but they’ve often had a striking impact in several court cases.

“We are now at a point where about 82 percent of cases that come to us result in a change of plea,” says Black. Sometimes moments before going to court, an individual presented with this evidence will suddenly change their plea. Not only does that save the courts the time and money of going to trial, it also prevents vulnerable victims from going through the harrowing experience of giving evidence in court.

What’s Next?

Even though this is a relatively new biometric measure, vein pattern analysis is becoming an emerging science in the forensic field. CAHID is continuing to improve on this technique while working with police and investigative agencies across the UK, Europe and even the FBI.

Black says the next step is to try and automate the process. In a recent paper in PLOS ONE Black and her colleagues showed that machine learning could predict sex, height, weight and foot size accurately from hand photos.

“It does take us a very long time to extract all the information from a photograph or video,” says Black. “If we can automate the extraction process of these anatomical features, then we could set algorithms that allow you to go through the millions of images held on databases by police forces. It could also give us the opportunity to link perpetrators in different cases. This is really quite exciting.”